Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Friday, 24 November 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Mohan Mendis

By Mohan Mendis

It has been made known that the Sri Lanka Tea Board is now finalising plans to embark on an ambitious international promotional program to promote the tea produced in our country. We have no information available yet of the campaign details but we assume that Ceylon Tea will be portrayed as being superior to any tea in the same category originating from any other producing country.

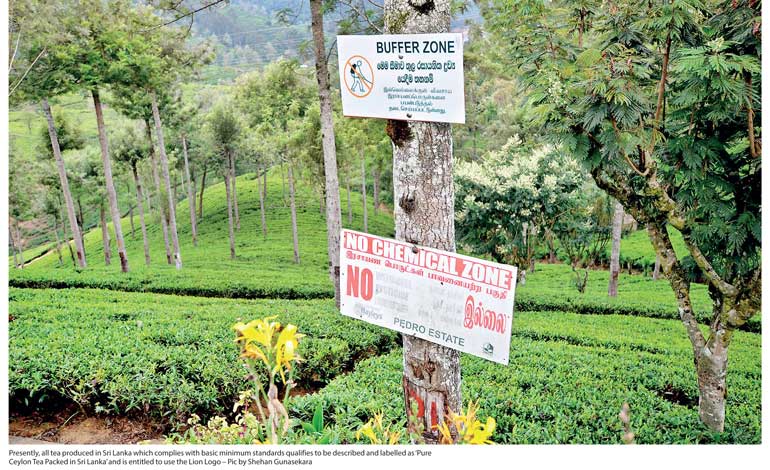

Presently, all tea produced in Sri Lanka which complies with basic minimum standards qualifies to be described and labelled as ‘Pure Ceylon Tea Packed in Sri Lanka’ and is entitled to use the Lion Logo – The Symbol of Quality, as commonly depicted on the packaging. The mark itself has undergone a few minor changes over time but the same ‘spotted’ Lion has been running for over half a century.

The mark widely registered in many countries is a stylised Lion upholding a sword (as in our National Flag) but having 17 spots as seen in the picture. This symbol was conceived when Ceylon Tea and its marketing activities were largely controlled and directed by London and I believe the 17 spots represent the 17 main markets in which Ceylon Tea was found to be thriving in at the time the symbol was conceived.

“Unusual, one might think, as lions are neither indigenous to, nor found roaming wild in the country. So, why the lion? And even more curiously why spotted? The answer is in legends that stretch back to the early centuries of Sri Lanka’s early history. Prince Vijaya, the first recorded King of Sri Lanka (543-503 BCE), was from India and believed to be the part lion on his maternal side. When he arrived in Sri Lanka he brought a flag featuring a lion denoting his lineage. The powerful king of beasts became the symbol of the newly formed kingdom of Tambapanni through to present day Sri Lanka, so named since its independence from British rule in 1948.”

In all probability it is this symbol that would be used in promotion and advertising as the distinctive ‘mark’ to identity Ceylon Tea and to distinguish it from others in the proposed campaign.

In regard to the ‘spots’, ironically in the present day reality of how people perceive Ceylon Tea, the spots more fittingly impute and imply the taint and blemish that consumers discover in products marketed worldwide with the symbol of quality depicting pure Ceylon Tea.

While we have less control over what happens to our tea outside our country, I question the wisdom of even permitting all the tea produced in our country to use the logo as the distinctive mark to identify the supremacy of Ceylon Tea. That would be an unsustainable claim for supremacy?

Sadly, not all the tea produced in this country can find its place in that distinctive and special class we can justifiably promote and portray as being different and exceptional. It would be injurious to the preservation of the good name that Ceylon Tea still enjoys to label every tea grown and grade manufactured in Sri Lanka as supremely Ceylon Tea. It would be degrading and unfair to say the least, to the excellent teas that we do produce and to those who strive to excellence taking pride in what they deliver.

Is all tea grown in Sri Lanka today – ‘Ceylon Tea’?

So one does have to find a solution to protect the integrity of the brand we are trying to re-create and re-position. Continuing to sell all the tea we produce here as Ceylon Tea would be a mistake and only further grow the perception that Ceylon Tea is no longer what it used to be and continue to erode the brand image that Ceylon Tea labelled and sold as Pure Ceylon Tea once enjoyed by many. The growing suspicion that it is adulterated will have even wider acceptance. We know that in many markets, it is adulterated, and we have no control or power to effectively regulate those practices even within, let alone the practices we know take place without our shores.

Champagne

In a recent article written by a veteran in the industry and published in your newspaper reference was made to ‘Champagne’ as rigidly governed by the laws in force in France. I feel sure that it is not only the importation of equivalents and counterfeits that are prohibited but not all wines produced even in Champagne would pass the stringent controls imposed by the ‘Appellation Controlee’ of the region to be labelled as Champagne. The mere fact of where a tea or wine is grown does not by itself give it the right to be branded as supreme?

In the case of Ceylon Tea the wide variance in the characteristics of tea grown in the different districts and elevations and the significant percentage changes in the volumes produced in the Low Grown areas in the island in the last 50 years does not lend itself to the case to establish one brand into the future to signify ‘all’.

The case I am building up to, is the need to create a new and distinctive mark or marks, to distinguish those teas (and only those teas) we Sri Lankans can really be proud of to market to the world as unique, supreme, unequalled and matchless.

It is useful for us to understand at this time the history behind the emergence of this claim to superiority and how it came about and I have been consistently digesting the material published in 1967, in the book titled ‘A hundred Years of Ceylon Tea’ by D.M. Forrest and would like to quote from excerpts, but only confined in this article to the pages of the book relating to the subject I am writing about. The author who from 1945 served in the Empire Tea Bureau in the UK; as an ex journalist and war time official is amply qualified to add credence to the facts as recorded and this is reinforced by the extensive research to which he refers to in the preface to the book.

In fact, it is the Empire Tea Bureaux which evolved into the Ceylon Tea Centre and triggered of one country promotion. This I discovered was entirely due to fortuitous circumstances for Ceylon Tea and which gave eventually gave birth to Ceylon Tea Promotion.

Until that time, the slogans used to promote tea were generic campaigns – ‘tea as tea’ ‘join the tea set’, etc. All the tea producing countries were contributing to a common fund to promote tea drinking focusing on Britain, the Irish Republic, The USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Middle East, Central and West Africa, South Africa, Netherlands, Switzerland, and Denmark.

By the middle of the last century, after World War II, The International Market Expansion Board had emerged from its long twilight of rationing and restrictions and in 1952 were all set with a big budget for the next year approved by all the producing countries. It was then that Indonesia first, soon followed by Pakistan announcing they could not afford to pay their share while India withdrew from the Board altogether saying they could promote Indian teas by themselves than by subscribing to a general fund.

It was at this point of time that Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) being relatively much better positioned financially with large reserves following the Korean Boom and the prices fetched for rubber, decided it was the opportunity to advance and not a time for retreat and agreed to a full year’s contribution upfront! This decision by the other producing countries to withdraw was later a matter of regret to many of them we understand.

This sequence of events led to the whole focus of tea promotion in UK and its allied countries concentrating on encouraging traders and consumers alike to demand Pure Ceylon Tea. So it is a fact, whether we like it or not, that we owe the creation and origins of the Ceylon Tea Brand to the British. Of course it must be said in the same breath that they were the biggest beneficiaries of this course of events as most of the marketing was entirely in their hands and used by brands owned by British companies and emerging multi nationals. The survivors of the International Tea Marketing Expansion Board evolved into propagandists for Ceylon Tea and eventually became the promotion agency for the Ceylon Tea Propaganda Board.

The consumer demand for pure Ceylon Tea grew and where a “pure Ceylon was not feasible,” blends with a high Ceylon content became increasingly popular particularly with the Trade. Interestingly, even those blends which had a percentage of teas of other origins were permitted to use the Lion Symbol.

In regard to the raging debate amongst tea men rapidly developing into a storm currently, I found the following paragraphs from the book of great relevance and I quote the author’s words;

“Many of us who have lived for years with this problem have come to believe that somehow tea has taken a wrong turn in the world’s mass markets. Admittedly, the sheer size of the latter (as Tommy Lipton discovered all those years ago) would make it impossible to provide everyone with a fine aromatic tea from the mountains or plains of

“Which leads to another question. ‘Is Ceylon Tea then so different’? The sceptic interposes. Not so different as chalk from cheese or, say Lapsang Souchong from a strong black Assam. If one had to draw a simple distinction between typical Ceylon Tea and nearly all its rivals, I suppose the firmest claim would be for superiority of flavour. Nobody knows just how this comes about, but the fact is that so much of it is grown on open hillsides near or above the 4000ft. mark, with the sun shining on them, and the wind blowing in from the sea must have something to do with it”…

The time is right perhaps to re-create the brand image of Pure Ceylon Tea and restore its rightful place to its former pristine place and glory. It would be best left to marketing and communication specialists how best this could be conceptualised, designed and achieved but in order not to lose the link it is suggested we remain with a Lion mark, but this time without spot or speckle and not boxed-in as before. The tea regulators and administrators would also have a responsibility in establishing Appellation Controls in the different districts as in France for wine where teas to qualify to use the description on the label only if it truly represents the character of tea in that district, e.g. Uva, Dimbula, Nuwara Eliya, etc.

Perhaps the spotted Lion may be continued as it already has been widely registered and would remain the symbol of quality for products packed in Sri Lanka but clearly distinguished from tea from Sri Lanka that we wish to re-present as being supreme. For want of a better yardstick only tea fetching over a weekly regulated bench mark (bar) will qualify to find its place amongst the tea described Ceylon Tea Pure and Supreme. Such a measure would also encourage producers (at least some of them) to strive for excellence in producing teas of the finest quality on the one hand attaining the ‘premium’ label and also give solace to those marketers of Pure Ceylon Tea whose aim is to offer only the best, generating value for the country. The focus for these premium players would be less on volume with the objective being declared as being the best and not the biggest.

To protect the integrity of the new mark, products which are required to be packed in Sri Lanka will have to develop a method of tamper proof sealing. Many of us in the trade know what happens to our 10 kg packs outside the country?

This new mark would necessarily entail an unavoidable degree of investment for global registration. Sri Lanka would soon have in place new intellectual property laws as a signatory to the Montreal Protocol. This would give faster and greater protection to the new mark in all member countries with a single application.