Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday, 17 February 2023 00:40 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In the case of the Hambantota International Port, for example, any DAC member country or any multilateral lending agency would have taken due diligence by way of carrying out a technical feasibility study as well as a financial viability study before committing to fund this major infrastructure project

|

Introduction

This is a response to a Briefing Paper (No. 8 dated November 2022) written by Umesh Moramudali and Thilina Panduwawala entitled ‘Evolution of Chinese Lending to Sri Lanka since the mid-2000s – Separating Myth from Reality’ published by the China-Africa Research Initiative (CARI) of the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at the John Hopkins University (JHU) in the United States of America (USA).1

Moramudali and Panduwawala (2022: 33) maintain that there is nothing obscure about the data on Chinese lending to Sri Lanka (including to state-owned enterprises) because either they have been disclosed in the balance sheets of such state-owned enterprises or it could be obtained through requests in terms of the Right to Information (RTI) Act No. 12 of 2016. The foregoing statement by Moramudali and Panduwawala betrays an innocence and a naivete of global best practices in fiscal transparency. The absence of open access compels interested person/s to request such data either in terms of the Right to Information Act (aka Freedom of Information Act in some countries) or by any other means. What is required or mandated as a global best practice is the proactive disclosure of such information by both the borrower and the lender.

The Report on the Observance of Standards and Codes (ROSC) as mandated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) requires the member states to adhere to certain standards and codes on fiscal and monetary transparency.2 Accordingly, the fiscal risks of all public entities have to be disclosed in one single document, which was for the first time done in the Quarterly Debt Bulletin noted above. Citizens should not be made to utilise the Right to Information (RTI) Act No. 12 of 2016 to seek information on public debt, both domestic and external, or any other matter of public interest (or the public’s right to know). Proactive disclosure of information and data is the sine qua non for ROSC as well as for the open government initiative/partnership.3

Objectives

The purpose of this response is, firstly, to pinpoint the factual errors (both quantitative and qualitative) in Moramudali and Panduwawala (2022), and, secondly, to contest the “reality” the authors are attempting to illustrate with such studious endeavour.

More than the factual errors (both quantitative and qualitative), our main concern here is the interpretation of the facts and the conclusions drawn therefrom by Moramudali and Panduwawala (2022). Moreover, we will be pointing out certain instances where Moramudali and Panduwawala (2022) contradict themselves by demolishing and also affirming the so-called “myths” (“hidden debt”, for instance) in different places in the same Briefing Paper. The peer reviewer/s (if there were any) seem to have not noted these contradictions or anomalies.

A factual check

A factual check

Moramudali and Panduwawala (2022) estimate that the total outstanding Chinese loans to Sri Lanka at the end of 2021 were $ 7.4 billion out of a total “$ 37.6 billion” of the external public debt of Sri Lanka (excluding the CBSL debt)4 as at the end of 2021. They estimate the Chinese loans to be 20% of the total external public debt of Sri Lanka at the end of 2021.

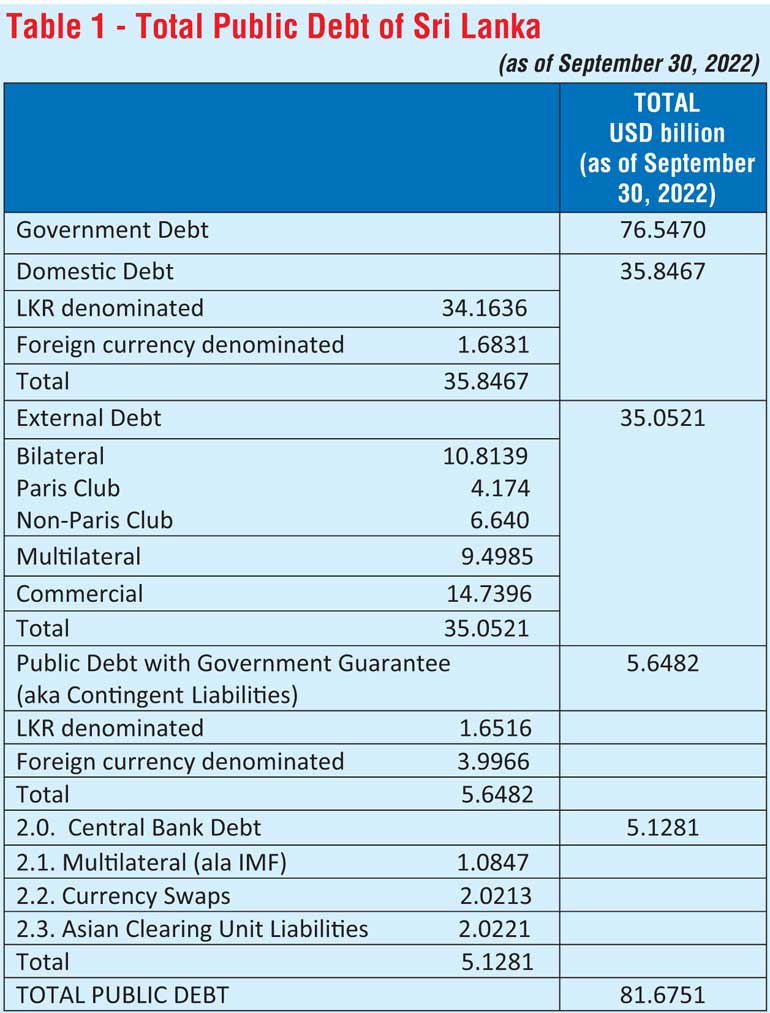

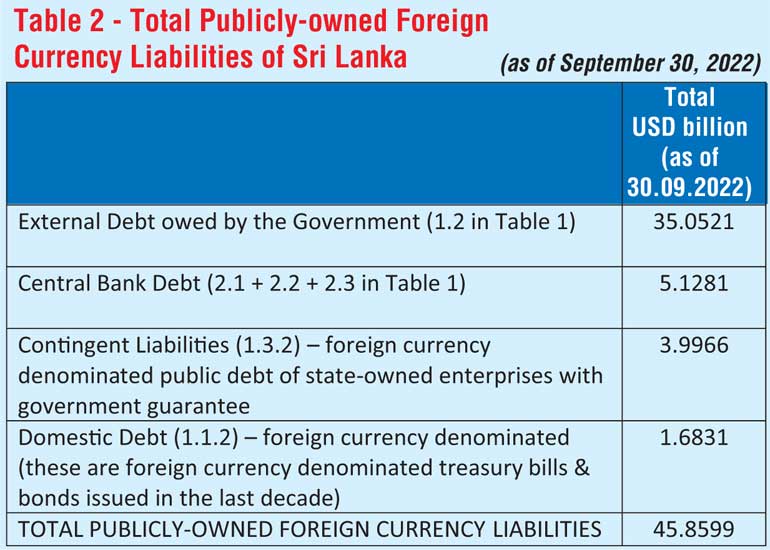

However, according to our estimate based on the Quarterly Debt Bulletin of the Ministry of Finance, the total outstanding publicly-owned foreign currency liabilities of Sri Lanka were almost $ 46 billion as of 30 September 2022 (see Table 2 for the breakdown). If we assume that Moramudali and Panduwawala’s estimate of the outstanding Chinese loans to Sri Lanka ($ 7.4 b) is correct, then the share of China in Sri Lanka’s total outstanding external liabilities was 16% as of 30 September 2022, according to our estimate.

While Moramudali and Panduwawala’s estimates are based on data up to 31 December 2021 ($ 37.6 billion), ours are based on data up to 30 September 2022 ($ 46 billion), the difference of $ 8.4 billion is certainly not due to the nine months of the time difference between the foregoing estimates. Of course, Sri Lanka did not receive $ 8.4 billion of external loans and credits during the nine months period between 1 January 2022, and 30 September 2022.

The aforesaid difference is because of what components of the public debt are included in the total foreign currency liabilities of Sri Lanka (see Table 2). For example, Moramudali and Panduwawala’s estimate of the total outstanding external public debt does not include the external debt of the CBSL, whereas we have included it in our estimate. This is simply because the liabilities (both domestic and external) of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka are ultimately the liabilities of the general public (i.e. liabilities of each and every citizen of this country). In fact, the external debt of the CBSL could be construed as “Contingent Liabilities”.5

In fact, we would argue that even our estimate of the total outstanding foreign currency liabilities of Sri Lanka (almost $ 46 billion as noted in Table 2) is an underestimation because we have not included the foreign currency debt of public enterprises that is ‘not guaranteed’ by the Treasury of Sri Lanka or the CBSL! For example, certain external borrowings of SriLankan Airlines (national carrier), Airports and Aviation Authority of Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA – see below with regard to the loans obtained for the Hambantota International Port), and certain external borrowings of state-owned banks (on the behest of the CBSL and the Treasury, of course) in the past were not guaranteed by the Treasury or the Central Bank. Though legally the Treasury or the CBSL is not responsible for the repayment of these non-guaranteed borrowings by such state-owned enterprises, morally and in reality, it is the Sri Lankan public that has to pay back such external foreign currency liabilities as well, by virtue of these public institutions being state-owned.

According to Table 1, the total public debt of Sri Lanka was $ 81.7 billion as of 30 September 2022, which is estimated to be over 190% of the GDP of Sri Lanka in 2022 in US dollar terms.6 Out of which, according to Table 2, $ 45.9 billion was the outstanding publicly-owned foreign currency (in US dollars) liabilities of Sri Lanka as of 30 September 2022. Therefore, the publicly-owned domestic currency (LKR) liabilities of Sri Lanka were $ 35.8 billion as of 30 September 2022 (at the exchange rate as of 30 September 2022). Thus, out of the total outstanding public debt of Sri Lanka as of 30 September 2022, 56% is foreign currency liabilities ($ 45.9 billion) and 44% is domestic currency liabilities ($ 35.8 billion at the exchange rate as of 30 September 2022).

We endorse the following call by Moramudali and Panduwawala (2022).

“……. public discourse, whether driven by media or academia, needs to take into account the complexities involved in how public debt is classified and reported in a country. At the same time, governments should ensure that public debt reporting is as simple, clear, and widely available as possible to facilitate open conversation.”7

It is precisely what is specified in the second sentence of the foregoing statement that has been lacking in Sri Lanka until the Quarterly Debt Bulletin was published by the Ministry of Finance recently. Whatever data and information the External Resources Department (ERD) of the Ministry of Finance disclosed on their website (www.erd.gov.lk) hitherto has been woefully inadequate. For example, the ERD disclosed only the external debt of Sri Lanka (which is understandable); however, even ERD’s external debt data did not include contingent liabilities in foreign currency, the external foreign currency liabilities of the CBSL, and foreign currency-denominated domestic debt.

A reality check

As we noted at the outset, our main concern in the Briefing Paper by Moramudali and Panduwawala (2022) is about the erroneous interpretation/s of the data and the conclusion/s drawn.

“We found no deliberately ‘hidden debt’ in China’s lending to Sri Lanka’s public sector. Publicly available data from a number of Sri Lanka’s public institutions provided full visibility for the US$ 7.4 billion in Chinese debt outstanding at end-2021. Chinese lending was then 19.6 percent of public external debt, much higher than the often-quoted 10-15 percent figures. A significant portion of Chinese debt has been recorded under state-owned enterprises, not the central government, but all of the Chinese debt was reported to the World Bank’s International Debt Statistics.”8

It does not really matter whether China accounts for 20% of the total outstanding external public debt of Sri Lanka (as estimated by Moramudali and Panduwawala in the following passage), or 16% of the total outstanding external liabilities of Sri Lanka as we have estimated, or any other percentage. It is the very first sentence of the foregoing passage that is of interest to us.

The real issue for us is whether the Chinese lending to Sri Lanka during 2007-2022 is predatory or not. It is on this issue that we contest the conclusions arrived at by Moramudali and Panduwawala that classifying the leasing of the Hambantota International Port (built at a total cost of $ 1.3 billion9) to a Chinese state-owned company as an “asset seizure” or “debt-for-equity swap” is a “myth” (see the following quoted passage). Moramudali and Panduwawala’s attempt to “firmly separate myth from reality”10 is what is contentious to this author.

“……. the 99-year lease of the (Hambantota) port in 2017 was a measure to address severe balance of payments issues, ... The lease proceeds helped improve foreign currency reserves and there was no debt-to-equity swap nor an asset seizure, contrary to popular narrative.”11

We agree with Moramudali and Panduwawala (2022) that, in a strictly legal sense the leasing of the Hambantota International Port (HIP) to a Chinese state-owned company in 2017 was not an “asset seizure” nor a “debt-to-equity swap’. It is not an asset seizure because the port was never made collateral for the loans from the China Exim Bank (China Export-Import Bank, aka ChEXIM) to build and subsequently expand the port. Asset seizure occurs only when the borrower had mortgaged the particular (immovable) asset as collateral for the loan/s obtained to build or expand.12 Usually, there is no collateral involved in any borrowings by a sovereign country.

Besides, it is not a “debt-to-equity swap” either, because the money received for granting 85% of the equity stake to the China Harbour Group (CHG – a state-owned company) in 2017 was not utilised to repay the loans borrowed for the purpose of building and expansion of the port. As Moramudali and Panduwawala (2022: 2, & 16) have revealed, the money received for the lease was utilised as “… a measure to address severe balance of payments issues…,” which we assume to have been used to repay one or more of the then maturing International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs).

Moramudali and Panduwawala (2022: 9) further claim that all the loans obtained from China for the building and expansion of the Hambantota International Port (HIP) are still being serviced by the Treasury of Sri Lanka, having taken over the loans from the balance sheet of the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA – a state-owned enterprise) in 2017. Between 2013-2017, HIP loans were included in the balance sheet of the SLPA as a ‘non-guaranteed’ foreign loan of the SLPA!13 This indeed was a classic example of a “hidden debt”14, which Moramudali and Panduwawala (2002: 2) painstakingly deny. It does not really matter whether it was hidden by the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) or the lender (Chinese financial institution). Both have an international obligation to be transparent.

While Moramudali and Panduwawala (2002: 17) confess that “The Auditor General noted that the outstanding balance of four ChEXIM loans for Hambantota port construction were not recorded in the government’s outstanding debt stock. While debt repayments were made on time by the Treasury and tracked by the ERD, outstanding loan amounts were not recorded by the SLPA or the Treasury in annual balance sheets.”, how could they assert that, “We found no deliberately ‘hidden debt’ in China’s lending to Sri Lanka’s public sector.”15

Further, whilst Moramudali and Panduwawala (2022: 2) at the outset deny there was any “hidden debt” in Chinese lending, later on, they also confess that “… there was indeed a portion of Chinese lending to Sri Lanka’s public sector that is apparently ‘hidden’ due to the complexities of debt classification and inconsistency of reporting standards across various public institutions and reports, especially with regards to debt recorded under SOEs. But in reality, they are not ‘hidden’ because at least some public institutions were reporting on these loans in publicly available reports and in data easily obtainable via RTI requests.”16

As noted at the outset of this response, obtaining information through an application in terms of the RTI Act is not what a transparent borrower and lender should impose on the citizens or any other interested party. Proactive disclosure of the information is the norm among the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) countries of the OECD. Moreover, Moramudali and Panduwawala (2022: 9) claim that “All five loan agreements (Phase 1, Phase 2, and bunkering facility projects) refer to contracts signed between SLPA and a Chinese supplier or contractors responsible for constructing the port, signed months ahead of the loan agreement signed between the GoSL and ChEXIM.”

The foregoing claim is once again a clear example of the predatory nature of the Chinese loans for the Hambantota International Port. How could the SLPA sign contracts with Chinese suppliers and contractors even before the loan agreement was signed?

To this author, the utilisation of the proceeds of the leasing of the HIP to augment the balance-of-payments or for the repayment of a maturing ISB/s is a dubious accounting practice of the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) and a gross violation of the International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS, 2002) of an accountable democratic state.

This is where the Chinese lender (EXIM Bank of China) has also erred. If it is indeed a responsible and accountable state-owned lender of the world’s second-largest economy, the EXIM Bank of China should have insisted that the money paid by the China Harbour Group (CHG) to the Government of Sri Lanka for the acquisition of 85% equity stake in the HIP should be channelled to repay the loans obtained from the EXIM Bank of China to build and subsequently expand the HIP. We sincerely believe that, if the lender for the HIP was a state-owned bank from a DAC member bilateral donor, the foregoing dubious transaction by the GoSL would not have been allowed. Therefore, China cannot absolve itself from culpability in the foregoing dubious transaction and accounting practice of the GoSL.

It is precisely the accounting malpractice of the GoSL and the collusion of China in this dubious transaction that had led to accusations of “asset seizure” and “debt-to-equity swap”. This author has come across similar unethical (if not illegal) practices in the Chinese lending to Pakistan and to some African countries as well.17

Secondly, the 6.3% interest charged on the first agreement dated 30 October 2007, for a loan of $ 307 million, and 6.5% interest charged on the second agreement dated 6 August 2009, for a loan of $ 65 million for the Hambantota International Port (HIP) by the Exim Bank of China were exorbitant (but may not be predatory) for an infrastructure project of the scale of the HIP. Moramudali and Panduwawala (2002: 6) have themselves admitted that the aforementioned interest rate/s were very high given that the effective LIBOR (London Inter-Bank Offered Rate – an average of interest rates of leading banks in London) rate was just 2% in 2009. However, we are aware that the first-ever International Sovereign Bond (ISB) floated by Sri Lanka in July 2007 incurred an 8.25% annual interest rate.

Quasi predatory lending by China

We characterise the Chinese lending to Sri Lanka as ‘quasi predatory’. The rationale for this characterisation is as follows.

What is predatory lending?

Predatory lending in financial parlance could be defined as the imposition of unfair, arbitrary, and even abusive terms and conditions on the borrower by the lender.18 Both the borrower and lender can be individuals, institutions, or nation-states. Such severe conditions can be aggressive sales/lobbying tactics, very high-interest rates (usually 3-digit interest rates), overcharging for administrative cost/s, non-disclosure of risk factors by the lender, failure to carry out due diligence with regard to the technical feasibility and/or financial viability of a particular project (such as the Hambantota International Port or the Colombo Lotus Tower (1,150 feet or 350 metres) – the tallest communications tower in South Asia), very high collateral requirement, a very stringent penalty in the event of default, etc., or a combination of the foregoing.

Why do we term the Chinese lending to Sri Lanka quasi-predatory?

Why do we term the Chinese lending to Sri Lanka quasi-predatory?

Whilst admitting that Chinese lenders (two major ones are the China EXIM Bank and China Development Bank) cannot be accused of charging very high interest rates (interest rates of Chinese lending have been always in single digit and lower than the interest rates charged by private international capital market lenders), excessive administration costs, or imposing very high penalty in the event of default, etc., with regard to its lending to Sri Lanka, to the best of our knowledge, China could be legitimately accused of failing to carry out due diligence with regard to the financial viability/commercial potential of most of the projects funded by it in Sri Lanka (including the Hambantota International Port (HIP), Mattala International Airport, Colombo Lotus Tower, etc.) and Sri Lanka’s capacity to repay the corresponding borrowings (by way of an in-depth review of the assets and liabilities of the Sri Lanka Ports Authority, the original borrower for the HIP as noted by Moramudali and Panduwawala (2022), for example), and resorting to aggressive marketing/lobbying tactics amongst Sri Lankan political leaderships and bureaucrats.

In the case of the Hambantota International Port (HIP), for example, any DAC member country (or Paris Club member country) or any multilateral lending agency (such as the Asian Development Bank, World Bank, or Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank) would have taken due diligence by way of carrying out a technical feasibility study as well as a financial viability study (including Sri Lanka’s capacity to repay given the then prevalent macroeconomic fundamentals) before committing to fund this major infrastructure project.

In fact, before approaching China for funding the HIP, the then Mahinda Rajapaksa regime asked India to consider funding it, which, it was reported then (and after) that, India declined. It was only after India’s refusal, the Mahinda Rajapaksa regime requested China for funding. Probably, even India (a non-Paris Club donor) was sceptical about the financial viability and anticipated commercial profitability of that mega infrastructure project.

In addition to the aforesaid failure of the Chinese lenders to take due diligence in the cases of funding prestige mega infrastructure projects (for example, HIP), Chinese state-owned infrastructure development companies operating in Sri Lanka for nearly 20 years now (such as China Harbour Engineering Corporation and China Harbour Group, for example) are alleged to be involved in aggressive lobbying for projects (even submitting unsolicited project proposals with suggestions for Chinese funding mechanisms) among the political leadership/s in power and senior bureaucrats. The foregoing are naturally predatory lending practices in financial parlance.

Additionally, Chinese state-owned companies could also be potentially involved in bribing politicians and/or bureaucrats in their host countries, which is termed “corrosive capital”. We would like to highlight three such concrete examples of abrasive/aggressive project grabbing by Chinese companies in Sri Lanka in the last few years and a concrete example of secrecy demanded by the Chinese Embassy in Sri Lanka with regard to the purchase of Sinovac COVID-19 vaccines by the Ministry of Health.

A Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) funded monorail was mooted during the closing stage of the Mahinda Rajapaksa regime mark 2 (2010-2014) to connect Thalawathugoda (outskirts of Colombo city) with the then-proposed Colombo Port City (subsequently called Colombo International Financial Centre) in the heart of the Colombo business district. It was carried forward by the non-Rajapaksa government between 2015 and 2019 but changed from a monorail to a Light Rail Transit (LRT) system (but JICA intact). Once again, Mahinda Rajapaksa’s brother Gotabaya Rajapaksa came to power in November 2019 and, as one of his very first major follies19, abruptly and arbitrarily cancelled the JICA-funded LRT system (at an anticipated cost of $ 1.6 billion) in January 2020 without providing any reason and without even informing JICA which had already funded a lot of the feasibility studies, etc., costing millions of dollars.20

By the abrupt cancellation of the LRT project without any reason, Sri Lanka not only antagonised the single largest bilateral donor to Sri Lanka between 1977 and 2006, viz. Japan21, the subsequent events exposed the Chinese hidden hand behind the cancellation of the LRT project funded by JICA. Immediately after the cancellation of the LRT project by the then Government in January 2020, the China Harbour Engineering Corporation (CHEC), which is the investor in Colombo Port City, was given the contract to build an elevated highway connecting the Colombo Port City and Thalawathugoda (replacing the proposed LRT system) without calling for open tender. This is a classic case of project grabbing by Chinese state-owned companies and predatory lending by Chinese state-owned financial institutions.

Similarly, the East Container Terminal of the Colombo International Port (one of the busiest ports in the Indian Ocean) was to be developed jointly by India, Japan, and a local private company (John Keells Holdings) in terms of a trilateral agreement signed between the then governments of Sri Lanka, India, and Japan in 2017 at an estimated cost of $ 500-700 million. This trilateral agreement was abruptly abrogated by the Gotabaya Rajapaksa government in early 2021 with the purported view to develop it entirely by the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA)22, a state-owned enterprise. However, subsequently, in January 2022, it was reported that the East Container Terminal at the Colombo International Port is to be jointly developed by China Harbour Engineering Corporation (CHEC) in partnership with a local company, Access Engineering, which was very close to the then ruling Rajapaksa family.23 Once again the erstwhile largest bilateral donor to Sri Lanka between 1977 and 2006 has been cheated and antagonised.24

Thirdly, the China Harbour Engineering Corporation (CHEC) is currently (February 2023) aggressively lobbying to proceed with the elevated highway connecting the New Kelaniya Bridge (at the entrance to Colombo city) and Athurugiriya (outskirts of Colombo city), which is mired in controversy with an ongoing investigation by the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery and Corruption (CIABC) as reported by one of the leading investigative journalists of Sri Lanka.25 This project is also being contested on the basis of negative environmental consequences.26 It is important to mention here that the state-owned parent company of CHEC has been sanctioned by the government of the USA.

Moreover, Sri Lanka bought Sinovac COVID-19 vaccines in June 2021 from China due to the delay in receiving the second dose of AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines from the franchised company in India. There were allegations in the media that the Ministry of Health in Sri Lanka was paying a higher price to purchase Sinovac from China than the price paid to AstraZeneca from India. When one journalist requested the Ministry of Health to disclose the purchase price of Sinovac, it refused to disclose the price because of a gagging agreement between the Chinese Embassy in Colombo and the local company involved in the purchase on behalf of the Ministry of Health.

It was reported that the Chinese Embassy in Colombo had informed the Ministry of Health that if the purchase price was made public the order will be cancelled27 ostensibly because of a “special price” offered to Sri Lanka.28 It is this kind of non-transparency in the official business dealings between China and Sri Lanka that leads to accusations of predatory practices and promotes rent-seeking/offering behaviour between the contracting parties involved in Chinese projects in Sri Lanka.29

What the aforementioned concrete pieces of evidence point to is that, while Chinese lending may not be termed predatory lending (because of the absence of very high-interest rates on their lending and there is hardly any evidence of overcharging in terms of administrative cost/s, etc.), Chinese lending could be reasonably characterised as quasi-predatory lending because of their lack of due diligence on project funding, and aggressive lobbying tactics with Sri Lankan politicians and bureaucrats.

We also would like to bring to the attention of the readers of this rejoinder that, Chinese lender’s huge upward revision of the interest rate (from 2.0% to 6.3%) on the very first loan for the HIP in 2007-200830 after the signing of the formal contract between the borrower and the lender could be construed as a predatory practice. A DAC member bilateral donor could have never done that.

Conclusion

Therefore, we would argue that Moramudali and Panduwawala’s characterisation that the accusations of asset seizure or a debt-for-equity swap by Chinese lenders with regard to the acquisition of an 85% equity stake on the HIP in 2017 are a “myth” appears to be an attempt to camouflage reality. It is precisely the aforementioned quasi-predatory practices by the Chinese state-owned companies and Chinese official lenders that elicit such accusations by investigative journalists and other concerned people, including some international development partners.

In sum, while we may characterise the borrowings by Sri Lanka through the floating of International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs) being similar to borrowing from individual money lenders in Sri Lanka, we may characterise the borrowings from China as being similar to the borrowings from microfinance institutions in Sri Lanka. The former could be characterised as predatory and the latter quasi-predatory.

Footnotes

1. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1quL7XFT0Xeo5J1S8Iw3wyscqZx0NN6C6aoG300aBuEc/edit

2. International Monetary Fund (IMF), Report on the Observance of Standards and Codes (ROSC). https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/rosc Accessed on February 05, 2023.

3. https://www.opengovpartnership.org/ Accessed on February 05, 2023.

4. Moramudali and Panduwawala, 2022: 2, 3, & 5.

5. International Budget Partnership (IBP), 2015, https://internationalbudget.org/wp-content/uploads/Looking-Beyond-the-Budget-4-Contingent-Liabilities.pdf; International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS), 2002, https://www.ifac.org/system/files/publications/files/ipsas-19-provisions-cont-1.pdf; Polackova, 1999, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/1999/03/polackov.htm.

6. Please note that the GDP at current prices is estimated to have contracted by 8% in 2022. In addition to this contraction, the huge surge in the exchange rate of the USD to circa LKR 360 at the end of 2022 (from around LKR 200 until March 07, 2022), contributed to the huge rise in the public debt to GDP ratio (in USD terms) in Sri Lanka. That is, the provisional estimate of GDP in current market prices for 2021 was 16,809,309 million rupees; the provisionally estimated contraction of the economy for 2022 was (-) 8%, which would have resulted in a GDP of 15,464,564 million rupees for 2022. This GDP estimate for 2022 when converted to USD at the end of the year exchange rate of 360 is US$ 42,957 million. See Table 2 in the following Special Statistical Appendix for GDP data up to 2021 https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/sites/default/files/cbslweb_documents/publications/annual_report/2021/en/16_S_Appendix.pdf. Accessed on February 05, 2023.

7. Moramudali and Panduwawala, 2022: 2.

8. Moramudali and Panduwawala, 2022: 2.

9. Moramudali and Panduwawala, 2022: 8.

10. Moramudali and Panduwawala, 2022: 4.

11. Moramudali and Panduwawala, 2022: 2, 14, & 16.

12. Moramudali and Panduwawala, 2022: 16-17.

13. Moramudali and Panduwawala, 2022: 9.

14. See, Polackova, 1999. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/1999/03/polackov.htm Accessed on February 05, 2023.

15. Moramudali and Panduwawala, 2022: 2.

16. Moramudali and Panduwawala, 2022: 33.

17. This is a research in progress by this author.

18. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/60671/1/526660597.pdf; https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304405X14000397?via%3Dihub Accessed on February 08, 2023.

19. Three other major follies of the deposed President Gotabaya Rajapaksa were the cancellation of the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) grant worth US$ 500 million from the United States, abrogation of the East Container Terminal project at the Colombo International Port, and the Singapore-Sri Lanka Free Trade Agreement.

20. Read the story by one of the leading investigative journalists of Sri Lanka https://www.sundaytimes.lk/230129/news/who-and-what-derailed-jicas-lrt-project-510078.html Accessed on February 08, 2023.

21. https://www.ft.lk/front-page/Japanese-giant-Mitsubishi-Corp-to-wind-up-Lankan-operations-next-month/44-745111 Accessed on February 10, 2023.

22. https://iesl.lk/SLEN/49/Development%20of%20East%20Container%20Terminal%20in%20The%20Colombo%20Port.php Accessed on February 08, 2023.

23. https://www.eurasiareview.com/13012022-china-enters-colombo-port-east-terminal-project-by-the-backdoor-analysis/ Accessed on February 08, 2023.

24. https://www.dailymirror.lk/breaking_news/Japan-asks-Sri-Lanka-to-make-efforts-to-regain-trust-of-Japanese-companies/108-253886 Accessed on February 10, 2023.

25. https://www.sundaytimes.lk/221030/news/bribery-com-summons-rda-project-unit-500423.html Accessed on February 08, 2023.

26. https://ejustice.lk/development-of-four-lane-elevated-highway-from-new-kelani-bridge-to-athurugiriya-phase-ii/ Accessed on February 08, 2023.

27. https://www.sundaytimes.lk/210627/news/sinovac-wants-price-kept-secret-any-disclosure-and-deal-is-off-447628.html Accessed on February 08, 2023.

28. https://www.newswire.lk/2021/06/28/chinese-embassy-defends-sinovac-vaccine-price-non-disclosure-agreement-with-sri-lanka/ Accessed on February 08, 2023.

29. https://www.icij.org/investigations/pandora-papers/sri-lanka-rajapaksa-family-offshore-wealth-power/ Accessed on February 12, 2023.

30. Moramudali and Panduwawala, 2022: 6.

(The full version of this rejoinder can be accessed at: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1quL7XFT0Xeo5J1S8Iw3wyscqZx0NN6C6aoG300aBuEc/edit)

(The writer is the Founder cum Principal Researcher of the Point Pedro Institute of Development (PPID), Point Pedro, Northern Province, Sri Lanka, established in 2004. He is a Development Economist by profession. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6443-0358. He has undertaken fiscal and monetary transparency reviews in Sri Lanka for Oxford Analytica, Oxford, UK, https://www.oxan.com/ from 2003 to 2006. Email: [email protected].)