Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Monday, 13 April 2020 15:57 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

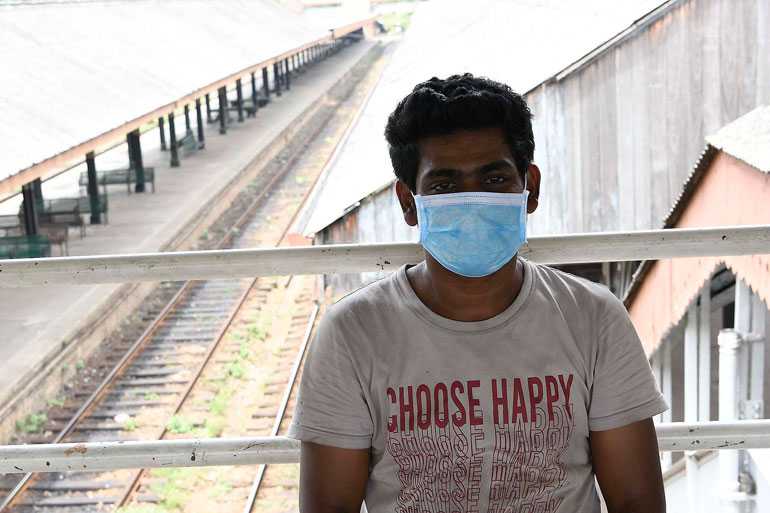

The pandemic tells who we are and where we are. Plagues hold a mirror to the society they afflict – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

“Epidemiology is like a bikini: what is revealed is interesting; what is concealed is crucial” – Peter Duisburg, Molecular Biologist, Berkley

“Epidemiology is like a bikini: what is revealed is interesting; what is concealed is crucial” – Peter Duisburg, Molecular Biologist, Berkley

On 2 March the President dissolved Parliament. Should he have done it? The answer is simple. There was no reason for him not to do it. He did not see the pandemic coming.

The bird sings not because it has an answer. The bird sings because it has a song. I did not vote for this President. That said, since a majority decided to pluck lemon, I am reconciled to drink lemonade in this hour of existential crisis.

No epidemiologist, no immunologist, no virologist told us or the President that we should not hold elections in April. No one knew. No one knew, because we did not have the means of knowing. That is the point of departure of this essay.

We do not have an authoritative national watchdog agency to audit disease control, protect environmental health and formulate guidelines of community medicine. Such an authority with the expertise and recognition to articulate an opinion could have made such a determination. The President would have listened.

The pandemic tells who we are and where we are. Plagues hold a mirror to the society they afflict. The Black Death epidemic in the 14th century laid the ground rules of the modern state. It devised methods of isolation and adopted rules of quarantine.

Societies had to evolve methods and means to halt terrifying disease that struck seemingly healthy people. Otherwise the ruling elite would have focused only on protecting themselves, their surfs and their slaves. There will always be forensic flunkeys of Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe types to trivialise liberty. The pandemic crisis has exposed the inadequacy of our public health administration. Our health system should not be the popularity vehicle for ministers of health. We must have a director of public health with a ‘weltanschauung’ that will build a new generation of researchers who will build links with his peers beyond our shores.

There is an evolving discipline of medical anthropology which addresses issues of stigmatisation and marginalisation. It explores new avenues of understanding the links between technologies of epidemic control and the distribution of mortality and vulnerability in and after pandemics.

This is timely warning that we should make greater investment in prevention-based healthcare. The coronavirus is on a mission of its own. It is surveying our political landscape. It is testing the tensions of our political systems. History will judge how we respond.

I invite the reader to visit the Government of Sri Lanka website http://www.epid.gov.lk/web/index.php?lang=en.

The website informs you that it has been last updated 4:28 p.m. on 7 January 2020, a week after China informed the WHO of the mystery virus. Its first situation report on the coronavirus is captioned novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) – Situation Report – 2020.01.28.

It imparts the following information:

It reports the global situation as 2,798 confirmed cases with 80 deaths. Local situation one confirmed patient.

It lists preventive modalities:

It informs you of steps taken for surveillance at airport:

Since 28 January the Epidemiology Unit has issued daily situation reports. Reproducing them serves no purpose in this essay. As Einstein famously advised, don’t bother with details you can find in some place. Knowing it is there is adequate knowledge.

Now, we should look up the situation report of the Epidemiology Unit of the Ministry of Health dated 1 March. This is what it reports:

See: http://www.epid.gov.lk/web/images/pdf/corona_virus_report/sitrep-sl-en-01-03_10.pdf

The Government website confirms that as of 1 March, the virus has been reported from 53 countries. The structure and substance of the website confirms a pivotal truth.

The Epidemiology Unit of the Ministry of Health functioned as an information clearing house. It is a far cry from a regulatory and supervisory agency dedicated to the study of global disease dynamics. The GMOA, the country’s premier trade union of doctors, has stepped in to fill that void.

They stepped in. They subdued the panic. As the saying goes, the GMOA rushed in not because angels feared to tread on the pandemic. When the pandemic hit us, there were no angels around. It is the GMOA that assessed the menacing magnitude of the pandemic in stark brutal probity.

Axiomatically the President is a decisive leader. I did not vote for him. If I am around, I will not vote for what he represents at the next Parliamentary Elections. I don’t idolise him. I respect him.

In times of panic and peril, a decisive leadership is what matters. That said, decisive leadership does not exclude or negate the need to consult and listen to experts. Truly great leaders listen to a wide range of opinions – not just those at the top or the sycophants hovering near. The great leader is focused on asking questions rather than trying to provide all the answers himself.

In his novel ‘The Plague”, Albert Camus makes a perspicacious observation: “A pestilence isn’t a thing made to man’s measure. Therefore, we tell ourselves that pestilence is a mere bogey of the mind, a bad dream that will pass away.”

Maybe, like Camus did, the President would have felt ‘that it was a bad dream that would pass away.’ Many did. Albert Camus wrote ‘The Plague’ as an attempt to capture the absurdities of life. To infuse his heart and intellect into the narrative of ‘The Plague’ he created a character – Jean Tarrou.

Jean Tarrou is a stranger, a visitor to the ravaged land – the plague-stricken city of Oran in then French Algeria. He keeps a diary of events of the plague. He works hard to organise sanitary squads. And then, days before the plague ends, he succumbs to it. The driven stranger trapped in tragedy, captures the essence of the panic and the totality of the peril that the plague brought.

“Each of us has the plague within him; no one, no one on earth is free from it. And I know, too, that we must keep endless watch on ourselves lest in a careless moment we breathe in somebody’s face and fasten the infection on him. What’s natural is the microbe. All the rest – health, integrity, purity (if you like) – is a product of the human will, of a vigilance that must never falter.”

In lockdown melancholia, I read and reread Albert Camus. In utter helplessness, I realise, as did Camus, “the bleak sterility of life without illusions”.

This essay, in these bleak times, is dedicated to my daughter. She is orphaned by the pandemic in a distant city state furiously, feverishly ‘working from home,’ so that she has no time to worry. She is too young to contemplate life without illusions. That state of mind is called hope.