Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday, 24 December 2024 00:38 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The recent salt shortage in the market, coupled with the Cabinet decision on 18 December 2024 to allow the import of 30,000 MT of non-iodised salt, has sparked widespread attention and discussions. Further, this decision has generated negative responses and uninformed statements from the general public, as well as politically driven media outlets. Despite the negativity surrounding this issue, the sudden attention on the Sri Lankan salt industry presents an opportunity to discuss the real situation and the importance of safeguarding this unique industry for future generations. Before delving into the specifics of the recent events, it is essential to establish an overview of the salt industry in Sri Lanka.

The recent salt shortage in the market, coupled with the Cabinet decision on 18 December 2024 to allow the import of 30,000 MT of non-iodised salt, has sparked widespread attention and discussions. Further, this decision has generated negative responses and uninformed statements from the general public, as well as politically driven media outlets. Despite the negativity surrounding this issue, the sudden attention on the Sri Lankan salt industry presents an opportunity to discuss the real situation and the importance of safeguarding this unique industry for future generations. Before delving into the specifics of the recent events, it is essential to establish an overview of the salt industry in Sri Lanka.

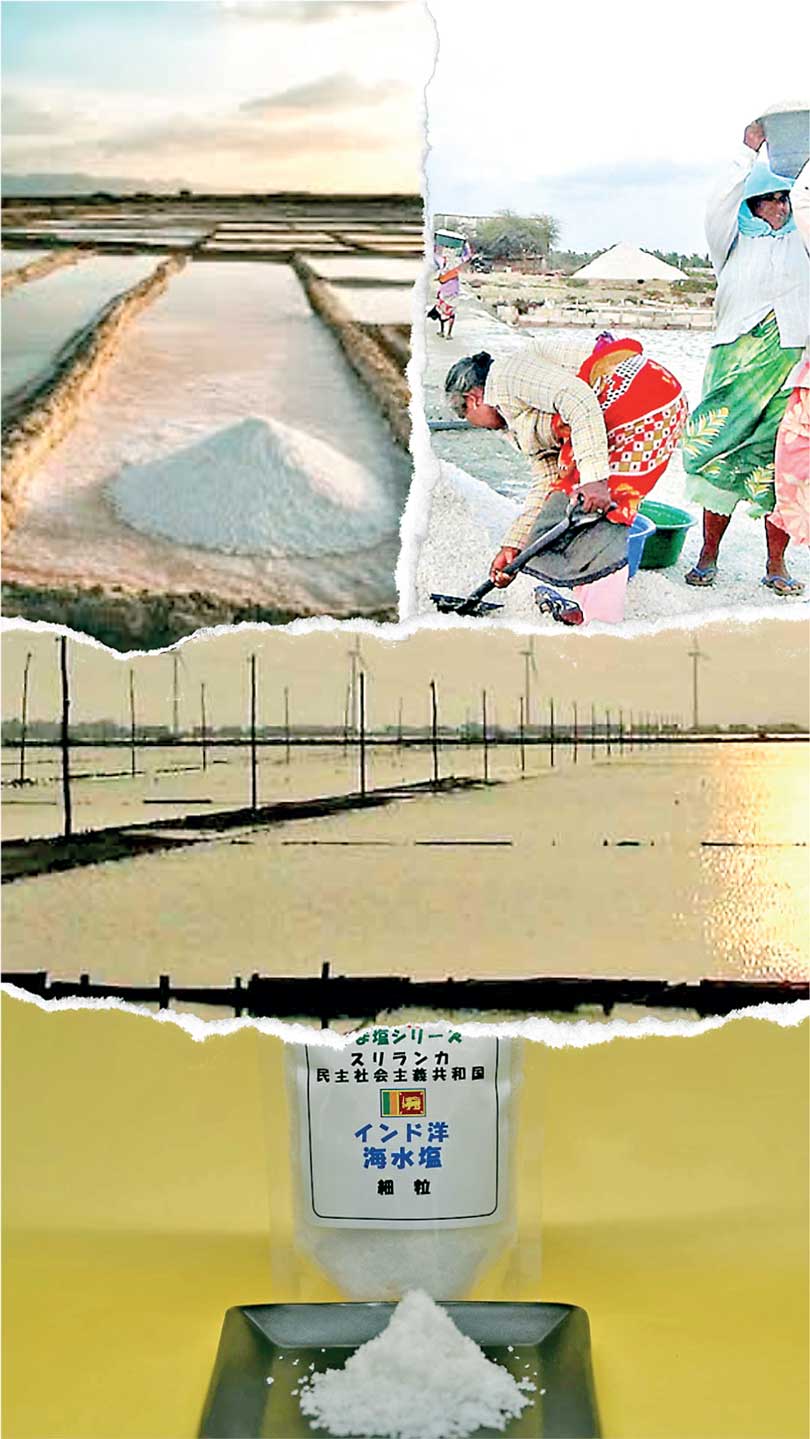

Sri Lanka boasts a well-established saltern industry, with Government and private-sector companies holding nearly equal shares and dominance in the market. The country is nearly self-sufficient in salt production, comfortably meeting the annual demand of approximately 180,000 MT for domestic and industrial purposes through a widespread saltern industry located in the coastal regions of Puttalam, Hambantota, Alimankada, Mannar, and Trincomalee. Pure Vacuum-Dried (PVD) salt is imported by the food and pharmaceutical industries, where higher purity and specific physical properties are required. However, this minor dependency on imports should not be seen as a weakness of Sri Lankan salterns, we should only see it as an opportunity for growth.

Small yet significant efforts of the Sri Lankan saltern industry

More interestingly, the author noted an update from a private-sector salt producer in Sri Lanka entering the PVD market segment and was thrilled to pick up a packet of PVD salt from a supermarket shelf. Furthermore, it is worth noting the small yet significant efforts of the Sri Lankan saltern industry, such as the production of crystal-clear “Singithi Lunu” salt for the export market. This product, created in the eco-friendly environment of the Bundala Saltern, is a specialty exported to the Japanese market. Harvesting salt is an ancient practice, but the history of the sector as an organised industry dates back to the colonial era of Ceylon, when prisoners were forced to work under the harsh conditions of salterns. However, the industry has undergone significant changes since then. Today, it is well-integrated into modern organisational structures that prioritise appreciable working conditions. At the heart of this industry are the salterns in the Puttalam area, where approximately 20,000 people depend on permanent or seasonal engagement with salterns for their livelihood.

If we have such a strong industry, what went wrong? What is the reason behind the recent salt shortage, leading the Cabinet to make the not-so-popular decision to permit the import of up to 30,000 metric tons of raw, non-iodised salt?

Salt industry in world is interestingly diversified which include solar evaporation, rock salt mining, vacuum evaporation and lake salt extraction as a basis to produce salt. Sri Lanka’s salt industry relies on solar evaporation, which is highly sensitive to climatic conditions. A hot climate with minimal rainfall is essential, and a completely dry period of 40 to 45 days is required for the process. Solar evaporation-based salt production depends on the crystallisation points in different tanks, making uninterrupted dry weather crucial for efficiency.

Adverse weather conditions

All the salterns located in the coastal regions of Puttalam, Hambantota, Alimankada, Mannar, and Trincomalee are highly dependent on the weather patterns endemic to their area for harvesting salt from sea water. However, during the Maha season, a critical period for Sri Lanka’s salt industry, the Puttalam area—a major production hub—experienced adverse weather conditions. Heavy rains and typhoons jeopardised the entire season for the salterns in the region, leaving some areas still submerged in storm water from recent events.

The Puttalam area encompasses 4,000 hectares of salterns, employing approximately 20,000 families directly and indirectly through its operations. It fulfils a significant portion of the country’s salt demand (45%, according to statistics from private salt manufacturers). This unexpected disruption has interrupted the salt industry’s operations, and projections indicate that without intervention, the first quarter of Sri Lanka’s domestic and industrial markets could face a severe salt shortage.

Despite having to face heavy criticism for importing salt to an island surrounded by sea, the Government took a commendable step by authorising State Trading Corporation (a Government-owned trending arm) to urgently import 30,000 metric tons of non-iodised salt. This measure aims to stabilise the supply chain by distributing the imported salt among industry players to meet market demand effectively.

Cabinet decision on 18 December 2024

“The salt production of Sri Lanka is sufficient to meet the domestic and industrial requirements of the country, and the salt yield depends on weather conditions. It has been observed that there may be a shortage of supplying salt in the domestic market for the domestic and industry requirements in the year 2025 due to bad weather in the country. As a remedial measure, the salt manufacturers have made a request to grant permission to import 30,000 metric tons of raw non-iodised salt as per the prevailing duty rates to be processed and supplied to the market. Accordingly, the Cabinet of Ministers has approved the joint proposal presented by the Minister of Trade, Commercial, Food Security, and Co-operative Development and the Minister of Industry and Entrepreneurship Development to import a maximum of 30,000 metric tons of raw non-iodised salt on or before 31-01-2025 through the State Trading Corporation and to supply it to the local market.”

While this firefighting measure is appreciable, it is time to implement a sustainable solution to address the issue, as unpredictable weather patterns have become inevitable worldwide. As part of the climate crisis, erratic rainfall and an increase in extreme weather events like storms and typhoons disrupt the solar evaporation process, which requires prolonged dry periods with minimal rainfall. Flooding from heavy rains can damage saltern infrastructure, contaminate salt beds, and delay production cycles, leading to supply shortages and economic losses. As climate variability intensifies, the saltern industry faces growing challenges in maintaining consistent output, threatening livelihoods and the stability of salt-dependent markets.

While permitting imports is a temporary solution, the Government must take immediate action to safeguard and strengthen Sri Lanka’s thriving saltern industry against these inevitable natural disasters. Such a solution is not simple – a multidisciplinary action is needed where policymakers, industrialists, and academics should team up towards a common goal. This is a call for such timely action.

(The writer is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Chemical and Process Engineering, University of Moratuwa. The author acknowledges Sandun Amarasinghe, a former chemical engineer who worked in a leading saltern in Sri Lanka for some insight he offered during the writing process. Dr. Subasinghe can be contacted via his email [email protected].)