Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday, 7 April 2023 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

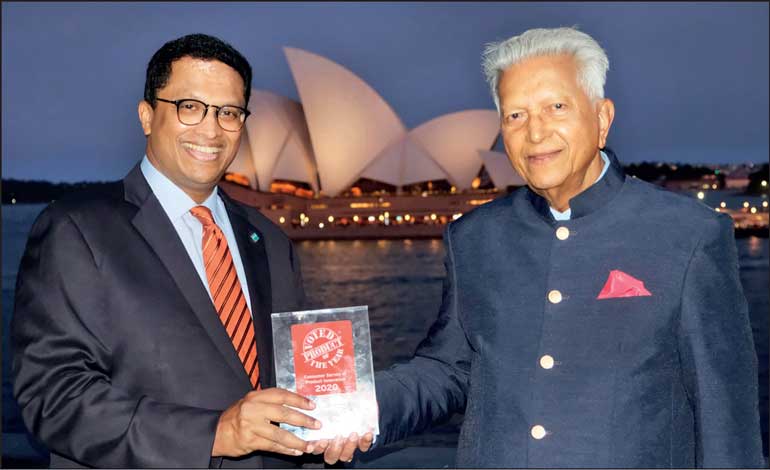

At the Australian Product of the Year Awards 2020

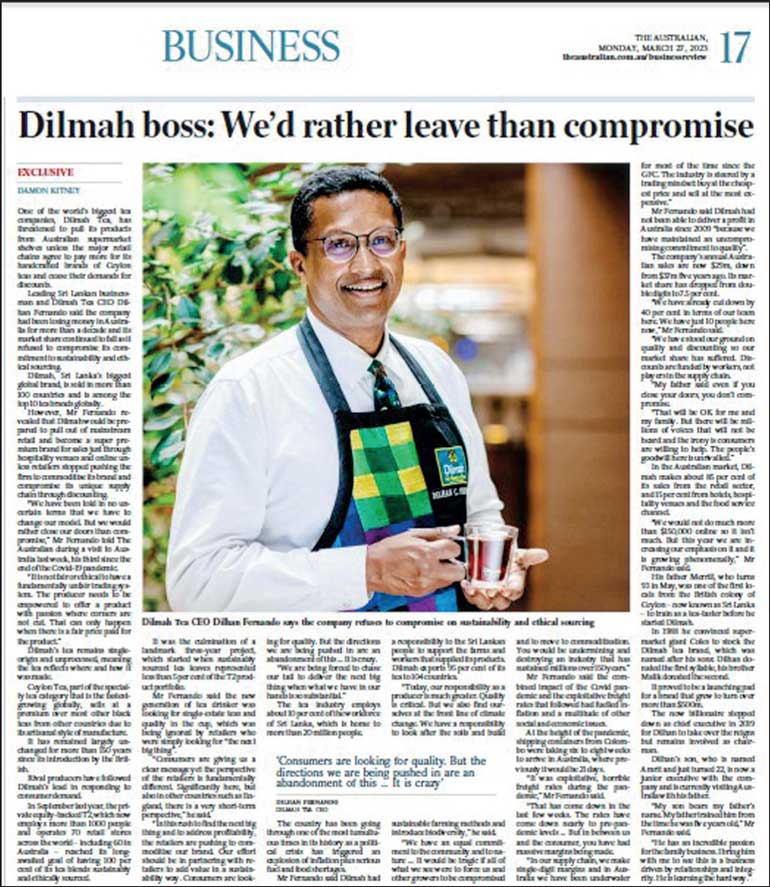

Writing in The Australian last week, Damon Kitney headlined coverage of a conversation I had with him a few days earlier, with my comment that “We’d rather leave than compromise.” What followed the publication of the story was a combination of anger, protest, criticism, misrepresentation and support; all of which demand explanation. The issue is important for us all, but also complex, so please forgive the lengthy explanation.

Writing in The Australian last week, Damon Kitney headlined coverage of a conversation I had with him a few days earlier, with my comment that “We’d rather leave than compromise.” What followed the publication of the story was a combination of anger, protest, criticism, misrepresentation and support; all of which demand explanation. The issue is important for us all, but also complex, so please forgive the lengthy explanation.

My father is a visionary; at the same time as his bulk tea export business was lauded by the Agency House Commission as being one of the most profitable Ceylonese owned tea businesses, he was looking beyond – realising that exporting tea in bulk (as a raw material) was not the future. He devoted his life to tea and relentlessly pursued his dream of launching his own tea brand. Along the way he suffered unexpected rejection by his bulk tea customers overseas in their indignation at a native from the colonies who was trying to usurp their role in branding and packing our tea. It was not too rosy for him back home either, for the predominantly bulk tea exporters in the tea trade feared that his efforts at branding and adding value to Ceylon Tea may annoy their customers too.

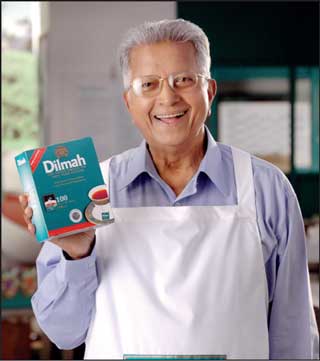

35 years and a thousand challenges later, Dilmah was born. My father was 55 years old at the time, a startup, disrupter and a passionate Sri Lankan teaman. The first packs of Dilmah, Pure Ceylon Tea, grown, ethically picked, perfected and packed at source, were shipped direct to Australia with earnings from their sale benefiting the economy of Sri Lanka and profits shared with my father’s tiny ‘family’ of workers as well as the less fortunate in the wider community.

|

| Merrill J. Fernando, who launched Dilmah with the gentle request, ‘do try it!’ |

Though every child delights in stories of farmers bringing their produce to market, it was the first time any tea grower had brought his tea directly to his customers. It was no different in coffee or in the cocoa (chocolate) industries. What my father achieved in eliminating the middleman and his profit, which had evolved gradually into greed and multi-origin blending to reduce costs, was genuinely fair trade; because packing, branding and value addition offer a larger share of the earnings from any product, especially agricultural produce, a fairer share of the earnings from her produce now benefited the economy of Sri Lanka, a rich nation subdued by colonialism and exploitation of her wealth in tea, spices and rubber by foreign traders.

My father is a visionary, and he is also a disrupter. The launch of the first grower-owned tea brand in the world formed a path for millions of growers around the world to discard the shackles that a colonial economic system and its heirs – multinational corporations and traders – imposed on them. As my father constantly protested, a trader succeeds by buying low and selling high – and so the cheaper the better, with taste, goodness and the interests of the consumer least among their priorities. That is extractivism, the exploitation of a country’s natural resources with minimal value addition, to benefit someone else.

The tea industry was going through something much worse for it was extractivism compounded by greed – not content with buying tea in bulk to exploit the quality and reputation of Ceylon Tea, trading brands – some of the world’s best known even today – mixed teas from different origins to reduce their cost. That robbed tea drinkers of the authenticity, taste, antioxidant goodness and assurance of pure origin teas. Even though often whitewashed with logos professing goodness, fair trade and more, this is no less exploitative to consumer and producer than colonialism.

The tea industry was going through something much worse for it was extractivism compounded by greed – not content with buying tea in bulk to exploit the quality and reputation of Ceylon Tea, trading brands – some of the world’s best known even today – mixed teas from different origins to reduce their cost. That robbed tea drinkers of the authenticity, taste, antioxidant goodness and assurance of pure origin teas. Even though often whitewashed with logos professing goodness, fair trade and more, this is no less exploitative to consumer and producer than colonialism.

My father saw the beginning of that terrible exploitation of our prized and beloved Ceylon Tea. That strengthened his commitment to what so many told him was an impossible dream. Those first packs of Dilmah Tea therefore carried within their teal green packaging the dreams of a teamaker and also the aspirations of millions of workers as well as the future of a sustainable and independent Sri Lanka.

At the time my father never anticipated the race to the bottom that would follow, initially in the guise of offering value to consumers after the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. Latterly discount culture grew as retailers relied more on the short term tactic to bolster profits, supporting the mirage of low price. That race was fuelled ironically by the popularity of tea, for as tea and its plant based goodness came onto the radar of multinational corporations they sought entry to the tea category and fought for dominance.

That was a tragedy as businesses built on the passion and commitment of family or owner operators were acquired and became part of a portfolio of products offered by corporations more interested in profit and dominance than taste and goodness. That transition signalled a change in focus, from passion for quality tea to profit. The commoditisation that followed echoes today as those corporations discard their discounted, bankrupted tea brands having wrung them of profit.

What all this has done to tea, an affordable luxury where the difference between a great cup of tea and an inferior one is only a few cents, is catastrophic for tea drinker, brand, worker, environment and Sri Lanka equally. Ellen Ruppel Shell explains: “If enough dishonest merchants water their milk, more and more customers will forget what normal milk tastes like and buy only the cheaper – watered down – variety.” The short lived allure of cheap price, and the commoditisation of tea has altered perception of a natural herb, so rich in variety, taste, luxury, and wellness. Too many tea drinkers have forgotten the richness, variety and taste of fine tea, too many lack the knowledge of proper brewing, too few are benefiting from the stress reducing, immune boosting, and multitude of other health benefits in fine tea. The promotion of low price as something beneficial has lured consumers into a terrible deception so convincing that even producers and exporters in tea growing countries have become sedated into compliance.

Every individual and every business bears a responsibility to be a part of the solution to the avalanche of health, economic, social and environmental crises that are bearing down on us. Producers around the world have special potential here, and each bears greater responsibility than ever before; growers are stewards of land and rural people, and their sustainability and growth are critical for the success of our nation. Taste is important, and so is wellness, but this goes beyond both because we are at the frontline of climate action, in the vanguard of the battle against social inequality, our actions critical in education, gender equality, education, innovation, food security, clean air, protecting watersheds and water quality, and a host of other critical aspects of life on earth that follow the pandemic as humanity’s next greatest challenge.

Every individual and every business bears a responsibility to be a part of the solution to the avalanche of health, economic, social and environmental crises that are bearing down on us. Producers around the world have special potential here, and each bears greater responsibility than ever before; growers are stewards of land and rural people, and their sustainability and growth are critical for the success of our nation. Taste is important, and so is wellness, but this goes beyond both because we are at the frontline of climate action, in the vanguard of the battle against social inequality, our actions critical in education, gender equality, education, innovation, food security, clean air, protecting watersheds and water quality, and a host of other critical aspects of life on earth that follow the pandemic as humanity’s next greatest challenge.

The decisions that growers make – whether or not to adopt regenerative methods to ensure soil fertility, sustainability, and climate resilience, our role in strengthening the rural economy with innovation, productivity and opportunities to stem unsustainable urban and international migration, our responsibility to protect watersheds and adapt to a changing climate, the responsibility we shoulder to the families of our workers not just to perpetuate tradition, but to educate their children and revitalise communities sustainably – all cost money. They can be implemented only if we receive a fair price for our efforts and recognition of the passion that most growers have for quality.

Agencies with vested interest, charities engaged in the business of charity and activists of all sorts point fingers at growers supported by images of impoverished people, under-nourished children and broken roofs forgetting that for every extended finger, three point back at the accuser; everyday low prices, Black Fridays, White Mondays and other record breaking retail events are built on the backs of workers and the environment, the ‘savings’ that consumers delight in are compensated by diminished opportunity for workers and their families, and too often also force environmental degradation.

We love tea, and we want to share the taste and goodness in fine tea but we also believe that while offering joy, wellness and serenity to our customers, Ceylon Tea has a critical role to play in a resurgent Sri Lanka. As producers our passion is for tea that celebrates the art of teamaking, something that can only happen in concert with nature. We want to share with our customers the indulgence of a natural, plant based herbal health beverage with infinite variety, a herb that delights as much as it protects. Our objective is not revolutionary, but boringly obvious; enabling growers enables quality, safe, tasty and healthy food while sustainable agriculture secures the survival of humanity and makes Earth habitable for unborn generations. Simple, and it starts with paying producers and genuinely ethical brands a fair price for a quality product.

We are a family business built on family values framed in our faith in God. Those values are sealed by the commitment of three generations of my family, cemented by a foundation in my father’s lifetime of devotion to tea. Formed unconventionally on the purpose beyond profit, our success, our faith and values demand integrity and impact. The fulfilment of that philosophy is expressed as much in the lives of less fortunate people that we are able to touch as we share our profits, as it in ecosystems restored, nature conserved and ecosystem services strengthened. That is why we can never compromise.

(The writer is the CEO, Dilmah Tea.)