Thursday Feb 12, 2026

Thursday Feb 12, 2026

Wednesday, 29 May 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

With President MS, Prime Minister RW and leaders of the Joint Opposition engaging in “revenge politics” (Stephen Long, Asian Tribune, May 2019), and as the term of the present Government and that of the President is drawing to a close, there is neither the time nor an inclination for the ruling regime to look for lasting solutions to the nation’s persisting problems. They are busy counting the size of their respective vote banks.

Already the Minister of Finance is forced to revise downwards the 2019 Budget forecasts and the economy is in dire straits. After the Easter carnage and subsequent communal violence the prognosis does not look good for the economy, which means the majority of people are destined to endure rising cost of living and prolonged misery.

Didn’t the President say earlier that the Budget is “not important”? Now, with the release of obstreperous Gnanasara who was imprisoned for contempt of court, the President has shown that it is not only the Budget and the economy but even the Judiciary is not important. All that the Yahapalana regime can do, therefore, is to look for band aid solutions to problems that require expert diagnosis and lasting remedies. One such band aid solution is the decision to control and bring all madrasas under the Ministry of Education. Not much details are coming out as to how it is going to be done and with what objective/s and outcome?

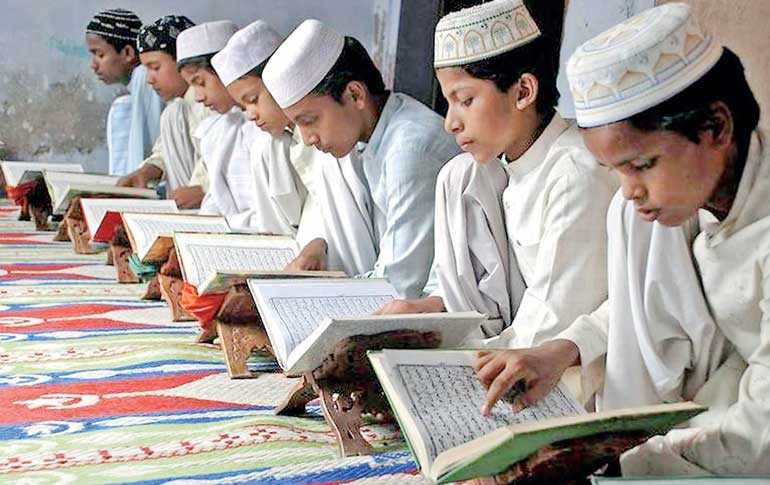

Madrasas, like the Buddhist pirivenas, are an integral part of a Muslim child’s early development. They impart not only the elementary knowledge about the Quran and the Prophet of Islam, but also the ethics and morals surrounding good human behaviour. In fact, madrasa education may have its roots in the early Buddhist monasteries or vihara in Central Asia. In Sri Lanka, however, its history goes back to the late 19th century when, according to the Department of Muslim Affairs, the first madrasa was established in Galle in 1870. Today, there are 1,669 madrasas and 317 Arabic colleges (Daily Mirror, 3 May 2019). In Kattankudy alone there are seven such colleges and 80 madrasas.

In the context of Sri Lanka, the term madrasa normally relate to the elementary Quran schools or maktabs attached to all the mosques in all Muslim villages and towns in the country. A child is normally expected to complete this level of education before it reaches the age of 10. In contrast, the Arabic colleges are the madrasas proper and the ones that train the ulema who graduate as imams and other religious functionaries, and are qualified to teach Islam and Arabic in Government schools and deliver sermons in mosques. This level of education takes about seven years or more to complete.

Is the Government going to take over only the 317 proper madrasas and make them Government-funded Muslim religious educational institutions? If that is the intention, why only the madrasas and not religious schools operating in other communities?

It appears that the main reason why it has picked the madrasas only is because of the general suspicion arising from the recent Easter massacre, that they have become the incubators for jihadists and extremists like Zahran Hashim.

To start with, this particular individual who engineered that infamy was a madrasa drop out who did not finish his education, but an autodidact who acquired his twisted ideas about Islam through contacts with foreign sources.

In an article published earlier, it was pointed out that, “So far, there is absolutely no hard evidence that madrasas in Sri Lanka are teaching jihadism and producing jihadists. What they are producing instead is a community of religious men and women who are ignorant of the cosmopolitan outlook of Islamic civilisation and therefore making the madrasa indoctrinated Islam an inward looking and exclusivist religion. How to make Islam cosmopolitan, inclusive and tolerant is the fundamental challenge Muslims are facing in plural societies like Sri Lanka” (Daily Financial Times, 20 June 2018).

It was in that vein another article advocated that madrasa education should be modernised (Colombo Telegraph, 6 February 2019). The existing madrasas are repositories and transmitters of past knowledge and not laboratories producing new knowledge to face modern challenges. They are churning out graduates who are mostly memorisers and summarisers rather than analysers and innovators. The latter skills require access to knowledge outside the medieval texts that are being taught in them, an expertise in modern learning techniques and in addition, familiarity with other languages apart from classical Arabic.

Lately however, and at least since 1990s, several madrasas have fallen under the influence of Wahhabi orthodoxy because of Saudi funding. That orthodoxy is also spreading through faculties and departments of Islamic and Arabic studies in universities. This does not mean that Wahhabism is solely responsible for the emergence of producing jihadists and extremists.

A Wahhabi can become a jihadist or extremist just as a secularly educated young man or woman can become one. In fact, among the Easter bombers were upper and upper middle class youngsters who did not go to the madrasas but were educated in Western universities. It all depends on the situation peculiar to each country and society. The post-2009 wave of far right Buddhist nationalism with its anti-Muslim focus and Islamophobia, and the failure of successive governments to check its spread have a lot to answer for the spread of extremism among sections of Muslim youth in this country. To blame the madrasas for this failure is to bark up the wrong tree.

Today, one doesn’t have to go to a madrasa or any other institution to get radicalised. We are living in an interconnected world and network society. By sitting at your home or in your bedroom with a laptop or television and watching the pictures of wars and bloodshed relayed almost daily from the Middle East and other Muslim countries, any young Muslim man or woman with an inkling of feeling for his umma (super community) could easily get agitated. He or she only needs some spark from somewhere to get into action, an important ingredient in the growth of home grown terrorism in the West. This fact must be understood by those who are ready to put the entire Muslim community on the dock for the crimes of a few.

That there is a need to check the spread of Wahhabism by modernising madrasa education is beyond question. In general, Wahhabism is an ultra-orthodox and purist ideology allowed to spread globally by the US and its Western allies to counter the threat of Iranian Shia radicalism in the aftermath of the Iranian Revolution.

Unlike Shia radicalism, Wahhabi orthodoxy does not advocate rebellion against governments or revolution. These ideologues would even prefer tyranny over anarchy. Saudi monarchy survives on the strength of Wahhabism. Philosophically, this ideology is essentially anti-Shia, anti-Sufi, anti-rational and even anti-science. It is this outlook that is retarding the culture of progress in many Muslim societies.

In countries like Sri Lanka, Wahhabis are creating religious tension and divisions both within and outside the Muslim community. There is also the danger that this ideology prepares a mindset that can be easily swayed by more vicious ideologies preached by groups like the ISIS. Wahhabism is all about iman (faith or belief), and groups like ISIS are all about (umma) belonging. It is the shift from belief to belonging that creates problem for Muslim minorities. The National Thawheed Jamaat is a classic example of this evolution from belief to belonging. The issue therefore is not to control the madrasas but to unlock the Wahhabi mindset to make it scientific and rational.

Madrasas are only one part of Muslim education. There are, in addition, Muslim schools with Wahhabi-leaning teachers, and university faculties and departments that teach Islam and Islamic studies with a pro-Wahhabi stint. The entire structure of Muslim education therefore needs reforming, and that cannot be done in isolation without reforming the national education structure.

Since independence education in Sri Lanka has become one of the vehicles to create a soft apartheid society. As a result, the standard of education has fallen, partly in response to competing populist demands from communal quarters and partly because of inadequate resources. This is one reason why there are tens of thousands of unemployable graduates in the country ready to be mobilised by leaders to advance chauvinist agendas.

What is needed now is a thorough overhaul of the national education system, including the madrasas, with a view to build a united Sri Lanka first and then to produce generations of literate, skilled and capable citizens to face a competitive world. This requires nothing short of a White Paper drawn by a team of educationists and experts. Anything less will be band aid solutions. Unfortunately, such an overhaul cannot be initiated by a Prime Minister and President who are about to say goodbye to their respective offices.

(The writer is attached to the School of Business and Governance, Murdoch University, Western Australia.)