Tuesday Mar 03, 2026

Tuesday Mar 03, 2026

Tuesday, 8 October 2024 00:27 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka’s economic woes are overwhelmingly a result of stupidity, not corruption

Jail the corrupt and bring our money back! This is the cry of our times. It rings from the four corners of the island and echoes across the usual divisions of race, religion, language and class. For our woes were caused by corruption, and redemption will be found when the thieves are caught and their loot returns to the public purse.

Jail the corrupt and bring our money back! This is the cry of our times. It rings from the four corners of the island and echoes across the usual divisions of race, religion, language and class. For our woes were caused by corruption, and redemption will be found when the thieves are caught and their loot returns to the public purse.

Alas this solution is no salvation. Much that was stolen never left us. Instead it was recycled at home for patronage and campaigns. Even if a few billion dollars were siphoned away, prospects of retrieval are slim. The World Bank’s report on stolen assets is called “Few and Far Between” for a reason. It laments that between 2006 and 2012 all developed countries only returned $ 423 million in stolen assets.1 Nor will jailing the chief miscreants prevent the same mistakes from happening again.

In reality, the diagnosis is wrong. Corruption is not the cause for this crisis. Sri Lanka’s economic woes are overwhelmingly a result of stupidity, not corruption. In Murtaza Jafferjee’s politer turn of phrase, it was misallocation, not misappropriation, that caused this crisis.

Corruption fails to explain Sri Lanka’s decision to borrow in foreign currency at high interest rates, or our decision to use that money to build white elephants. It cannot explain our choice to keep a war-time army, our choice to reject the $ 500 million MCC grant, our choice to cancel the LRT, our choice to ban organic fertiliser, our choice to unsustainably peg the rupee or our choice to cut taxes when we were almost bankrupt. It fails to explain any of the major causes of this crisis. Nor does it explain the crisis that arose in the 1970s as a result of N.M. Perera’s and Sirima Bandaranaike’s policies. Rather it was a toxic mixture of stupidity, ideology and a hubris born of insecurity that are to blame.

Consider the follies of the Matara-Hambantota highway, the Lotus Tower and the Mattala Airport.2 They cost over $ 2 billion. Some of that colossal sum was most likely stolen. This is an outrage and reflects a deep malaise in our polity, institutions and morality. But such corrupt transfers from the public purse to private pocket are not the cause of this crisis.

Cause for the crisis was waste

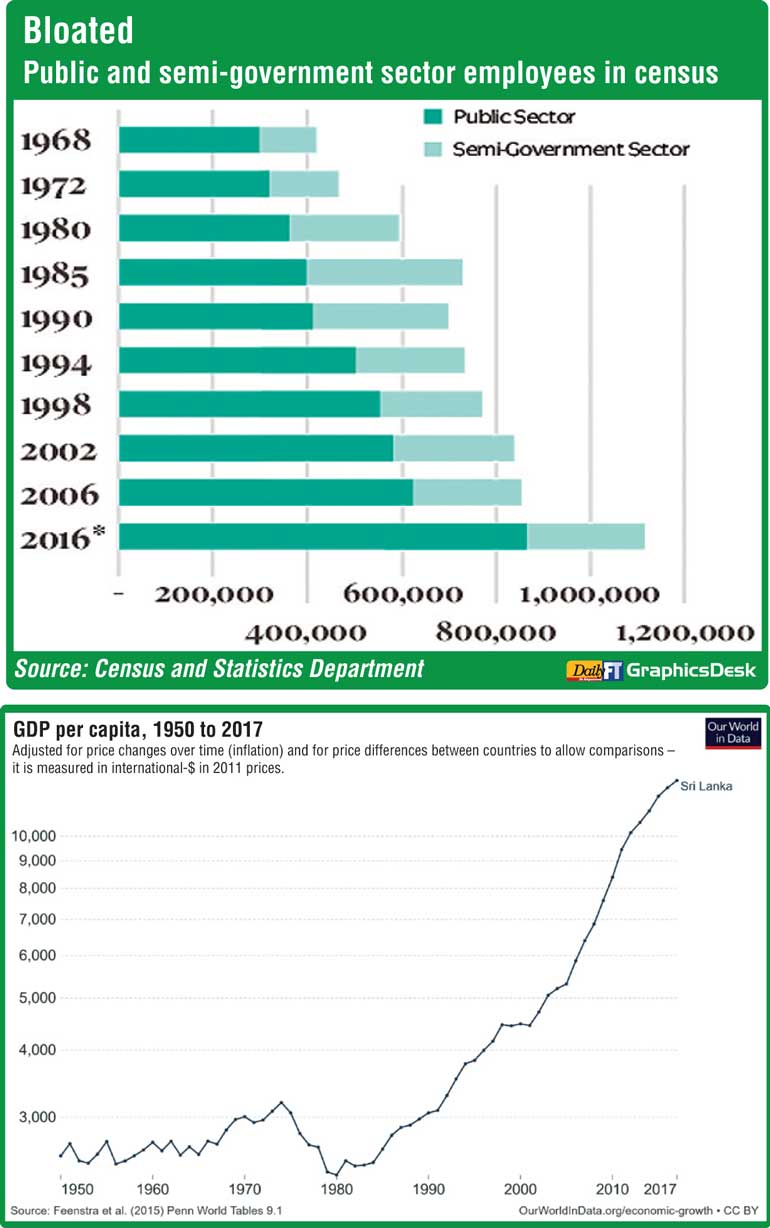

If there is one cause for this crisis, it was waste. We wastefully spent money on projects that didn’t pay for their loans. Middle-income status, the end of the war and a global liquidity glut gave Sri Lanka a credit card for the first time. Instead of using that credit card to invest, we were a prodigal country, consuming with no thought of tomorrow. The Lotus Tower and Mattala Airport are among the whitest of white elephants. A Moratuwa University study estimated that the Matara to Hambantota Expressway had a negative economic return. It is, after all, a highway to nowhere. Similarly, lakhs of jobs were handed out. The bloated public sector ballooned. These ‘development officers’ became a fetter on our development. We will pay their salaries for decades. And their pensions for decades more.

All could have been avoided if the mega-borrowings of the post-war decade were spent on sensible, high-return projects. We could have spent them on transport infrastructure like the LRT; on export infrastructure like industrial zones; on higher salaries for STEM teachers or on agricultural modernisation. These investments would have generated growth and tax revenue to enable us to repay our loans.

The corruption involved in the projects could still be the same as the white elephants. Consider, for example, if we had built the Colombo to Kurunegala expressway instead of the Matara to Hambantota expressway. Or double tracked the Kelani Valley line instead of building the Lotus Tower. A Mr 10%’s payoff would be similar in both cases. Even though his private benefits would be the same, the public benefits would be very different. We would enjoy higher growth and a better quality of life. Ironically, even Mr 10% would be better off. His cut would have been the same, but his popularity would wax rather than wane.3

The above argument is based on simple examples. But imagine if, with the same level of corruption, the tens of billions we borrowed was invested productively instead of frittered away on white-elephant infrastructure, inefficient SOEs and an oversize military? We may have caught up with some of our South-East Asian neighbours. We would certainly not have had this economic crisis. And our politicians would have been just as rich and corrupt.

Survey the rest of the developing world. Although impossible to measure with any accuracy, it is very likely that Sri Lanka is less corrupt than Tamil Nadu, China in the 1980s and 1990s or much of South East Asia. As James Crabtree reminds us in his fecund Billionaire Raj, corruption isn’t holding South India back.

“Even at the time of her death few bothered denying that Jayalalithaa had run a state built on graft. Court records showed her personal wealth to be a little under $ 10 million, a significant sum, but hardly enormous. Her indignant supporters often pointed to the far bigger sums extracted by supposedly respectable politicians in New Delhi. These holdings in turn were trivial next to the vastly larger amounts she and her fellow Tamil politicians needed to bankroll their election spending and patronage networks. Yet Jayalalithaa and her rivals managed to raise these funds without greatly damaging their state’s economic record, or indeed causing the kind of blockbuster scandals that in time brought New Delhi grinding to a halt.

This style of crony capitalism distinguished India’s five prosperous southern states – Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh – from the laggards of the north. Of these, all except Kerala were stunningly corrupt. Karnataka was India’s most graft-ridden state, one survey suggested, while Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu came in second and third. But all were also economic success stories, with development levels that stood closer to south-east Asia than sub-Saharan Africa… ‘In the south, you can say that politicians learned to steal, but to do it while expanding the cake at the same time,’ as Devesh Kapur, a professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania, once put it to me. ‘In north India they just went about taking as much of the cake for themselves as they could, and soon there wasn’t any cake left for anyone else.’”

What can we do to make policy less stupid?

We are all asking the question, what can we do to be less corrupt? That is good. But alongside that question, we need to ask ourselves, what can we do to make policy less stupid? The answers deserve an essay of their own. But if we had to pick one change, it would be eliminating our system’s single point of failure. Since 1978, economic decision-making has been concentrated in the President’s hands. The recent Central Bank Act reduced some of these powers. But the Executive Presidency remains clothed in immense and overmighty power, including in the economic realm. For example, as Finance Minister, the President often changes swathes of taxes at the stroke of a pen. Disrobing the office of these awesome powers is the true start of system change. We have vested too much power in the hands of a single mortal. It is too great a responsibility for even the best of us to bear. It must be restrained by vesting it in the collective deliberation and decision-making of Parliament.

Abolishing the Executive Presidency and reducing individual discretion is unlikely to make policy much smarter. But it will make the truly stupid less likely. We will have fewer colossal mistakes of the Jayawardena or Rajapaksa variety.

Making smarter policy is much more complicated. It demands, among others, a quality civil service, wiser politicians, an enlightened media and rigorous universities. These aims may sound lofty but progress is possible. Some initial quick wins:

nRectify the scandal that is SLAS selection and promotion by overhauling SLAS entry and efficiency bar exams.

nReform the electoral system to enable men and women of substance, commitment, and the ambition to make a mark on mankind to run, and to win. The mixed member system will help by creating safe seats and increasing the size of party lists.

nLegislate ownership and disclosure requirements for media firms that determine the flow of information, like we already do for banks that determine the flow of capital.

nOverhaul the University Grants Commission, making appointments more diverse and subject to Constitutional Council approval

In addition to investing public resources more wisely, the state needs to remove the handcuffs on growth. These require privatising SOEs, reducing tariffs and reforming factor markets. But that is beyond the scope of this essay; it suffices to say the IMF programme is a necessary but insufficient condition for growth.

Yes, corruption is corrosive. It is a moral outrage that must be checked and punished with the full force of the law. But I fear stupidity more. If Sri Lanka is to avoid another collapse, it needs more than moral outrage; it needs to dismantle the machinery of bad decisions.

Luckily, there is often no tradeoff between fighting corruption and fighting stupidity. The causes have similar roots: too much power concentrated in the hands of too few, a political culture that prizes loyalty over competence, and institutions designed to enable—not check—foolishness and vice. Alongside jailing the corrupt, true system change is abolishing the Executive Presidency, strengthening parliament and modernising Sri Lanka’s state and deliberative institutions. And it is about ideas, freeing our minds so that we can seek truth from facts; letting practice, not theory, be the sole criterion for testing the truth.

Footnotes:

1https://star.worldbank.org/blog/fifteen-years-star In its 15 years of existence the Bank’s much vaunted StAR unit only succeeded in freezing or recovering $1.9 billion. For context, Sri Lanka’s external debt alone, standing at $36 billion, is more than 18 times greater than this sum.

2The mostly unused $164 million Medawachchiya-Mannar railway is a folly of similar proportions.

3And with growth, his 10% bounty on future projects would be fatter.