Friday Apr 18, 2025

Friday Apr 18, 2025

Tuesday, 6 July 2021 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa

Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa

State Minister Ajith Nivard Cabraal

Central Bank Governor W.D. Lakshman

On 4 March 2020, just three days before Lebanon’s worst financial crisis in its history, its Government said it was “lurching from one extreme solution to another” in a bid to escape sovereign default by repaying $ 1.2 billion loan maturing in five days.

On 4 March 2020, just three days before Lebanon’s worst financial crisis in its history, its Government said it was “lurching from one extreme solution to another” in a bid to escape sovereign default by repaying $ 1.2 billion loan maturing in five days.

On 7 March 2020, Lebanon declared that it could not meet its debt obligations and halted the 9 March bond payment of $ 1.2 billion, setting the heavily-indebted state on course for an unprecedented sovereign default as it grappled with a major financial crisis.

Before 7 March last year, there were a number of signs of a possible sovereign default in the Middle Eastern nation, but its Government never told the public there was a possible default. Instead, it never admitted that the debt was unsustainable and it often rhetorically said it had options in hand to face it.

And that’s the nature of sovereign default if governments conceal the truth from the public. Common people will never have any idea until their government actually defaults a sovereign debt.

It was just before the sovereign default that Lebanese Prime Minister said foreign currency reserves were at a “critical and dangerous level,” adding that basic imports would soon be affected.

Before the sovereign default, Lebanon was struggling with a deep economic crisis after successive governments piled up debt following a 1975-1990 civil war with little to show for their spending spree.

Its financial collapse since 2019 is a story of how a vision for rebuilding a nation once known as the Switzerland of the Middle East was derailed by corruption and mismanagement as a sectarian elite borrowed with few restraints.

High rise building after war

Capital Beirut, which was levelled in the civil war between 1975-1990, rose up with skyscrapers built by international architects and swanky shopping malls filled with designer boutiques that took payment in dollars.

But Lebanon had little else to show for a debt mountain equivalent to 150% of national output, one of the world’s highest burdens. Lebanon had to borrow new money to pay existing creditors, a practice which some economists described as a “nationally regulated Ponzi scheme”.

A reduction in the dollar inflow after the start of a war in neighbouring Syria dented the country’s economic prospects, which pushed to country to seek more dollar loans. But the central bank, Banque du Liban, introduced ‘financial engineering,’ a range of mechanisms that amounted to offering banks lavish returns for new dollars.

Improved dollar flows showed up in climbing foreign reserves. What was less obvious – and is now a point of contention – was a rise in liabilities. Meanwhile, the cost of servicing Lebanon’s debt surged to about a third or more of budget spending.

The budget deficit rocketed and the balance of payments sank deeper into the red, as transfers failed to match imports of everything from staple foods to flashy cars. Lebanon imports are much higher than exports, while its economy is choked by one of the world’s largest debt burdens as a result of years of inefficiency, waste and corruption.

Ten years ago, GDP growth was ticking along at 8-9% a year in Lebanon. But that fell sharply for several reasons including the impact of war in Syria, wider regional turmoil and diminished capital flows from abroad.

No to IMF

With few sources of foreign exchange, Lebanon depended on its diaspora to remit cash to the banking system, which is then recycled to finance imports and the state deficit.

But despite increasingly high interest rates, the foreign remittance inflows slowed. This has led to a scarcity of dollars and pressure on the Lebanese local currency pound which has weakened on a black market. And the weaker pound started to push up prices and this cost of living before the default.

The Lebanese pound currency which was pegged against the US dollar at around 1,500 pounds started to depreciate since August 2019 and its black market price hit a record low of around 2,400 pounds just before the default with more than 50% depreciation. Now the currency is hovering above 17,000 pound per US dollar.

The bulk of the Government’s spending is absorbed by debt servicing and paying a bloated civil service stacked with political appointees.

Despite years of warnings about the need to reform and rein in the deficit, governments failed to act.

There were wide calls for Lebanon to seek the International Monetary Fund (IMF) financial support.

But Hezbollah, a powerful group backed by Iran, is opposed to a deal with the IMF, because it would likely seek to impose stiff fiscal conditions that could cause a popular revolt. So the Government opposed to that idea.

Unlike many Arab countries, Lebanon is not dominated by one strong ruler but has a number of leaders and parties with sway over the country’s various sectarian groups.

Critics say the political system kept the ruling caste in power indefinitely and allowed politicians to put their own interests above those of the state. Before the default, there were massive protests countrywide against Government regulations that stopped the people from withdrawing their funds from banks. The protests are part of a broader movement that started in October 2019 in response to proposed taxes on WhatsApp, a messaging service.

The movement quickly snowballed into an anti-Government protest that forced then-Prime Minister Saad Hariri to resign. But that did not stop the protests.

Fractured politics

The protesters accused the political elite of exploiting State resources for their own benefit through networks of patronage and clientelism that mesh business and politics. The protesters’ demands included not only removing the elite, but also overhauling the system.

Lebanon’s fractured politics was also vulnerable to foreign interference that has long fuelled domestic crises. The Government lost the public trust and that resulted in continued protests on the road. Further economic deterioration, including the risk of a sharp currency devaluation also exacerbated social tensions.

IMF officials, however, were called in later after the default to help find a solution to manage Lebanon’s overwhelming debt amid the worst financial crisis since the Mediterranean country’s brutal 1975-’90 civil war.

However, now without a new government after the last year Beirut’s port blast, Lebanon cannot secure an IMF program or international donor support, and it cannot restructure its $ 90 billion sovereign debt pile.

In summary, the sequence of what happened in Lebanon was its post-war reconstruction was derailed by a corrupt elite amid slowed remittances which were vital to balance Lebanon’s BOP. The central bank ‘financial engineering’ kept inflows going and the Gulf halted support as the Iran’s influence in Lebanon grew. Then unfettered spending finally brought nation to its knees

Similar to Sri Lanka?

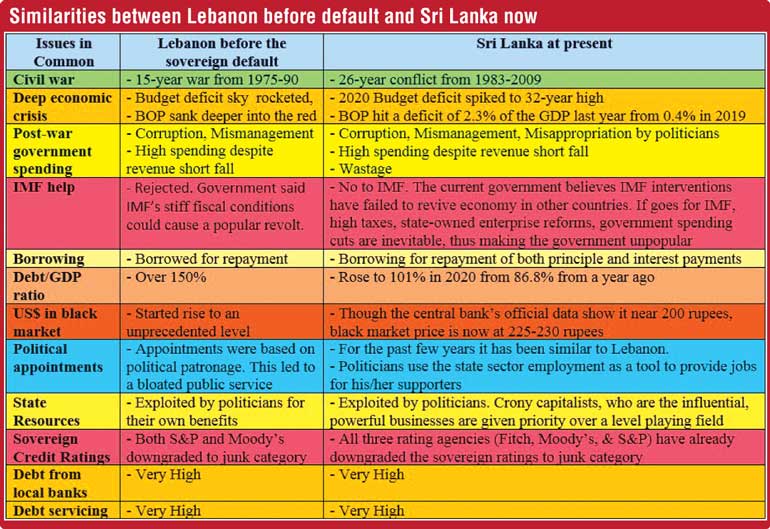

Many of the tell-tale signs in Lebanon just before the sovereign defaults are happening now in Sri Lanka.

The Government vehemently rejects claims of possible sovereign default. Despite all three international rating agencies having said the island nation’s external debt is unsustainable, the Central Bank and Finance Ministry have rejected such claims.

Central Bank Governor W.D. Lakshman last month in a lengthy statement said the Government could manage its sovereign debts and some media were just speculating.

The Government has to repay $ 1 billion principle payment on 27 July that Sri Lanka borrowed via sovereign bonds when the current Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa was the president in 2011 at 6.25% yield. The Government will pay this from its dwindling foreign exchange reserves as it is unable to tap the international capital market because of higher risk premium owing to its lower credit ratings.

Sri Lanka, like Lebanon, is also struggling with a deep economic crisis after successive governments piled up debt amid a 26-year civil war. Some of its infrastructure projects, financed by foreign loans, are yet to give any substantial return on investments.

Corruption, mismanagement, wastage, and misappropriation of funds by ruling politicians have been amply reported in local media.

The debt mountain is equivalent to 101% of national output last year. The $ 81 billion economy is now borrowing new money to repay its existing creditors. The COVID-19 pandemic has wiped off its nearly 5% revenue of the GDP from tourism. The Government has announced incentives to send more remittances, put brakes on imports, and encourage the domestic economy.

The budget deficit in 2020 has risen to 11.1% of the GDP, its worst since 1988. The balance of payment (BOP) turned to a deficit last year. The country’s GDP growth has fallen to very low numbers. It contracted to its worst level last year mainly due to lockdown owing to pandemic.

The key difference is Sri Lanka’s economy has worsened in the last 16 months mainly due to the pandemic and the things would have been completely different if not for COVID-19 whereas Lebanon’s economic crisis could not be managed by its Government.

“We have alternatives”

Sri Lanka’s current Government is also maintaining a policy stance of not seeking IMF help because of past experience despite some Opposition members urging it to start early talks with the IMF.

“Some people wish to push us for the IMF and they know what will happen if you go for IMF. That happened to them. They went to IMF, they had to face various economic hardships,” Ajith Nivard Cabraal, State Minister in charge of money and capital markets told media last week.

“We have alternatives. Already the Government and the Central Bank are in the process of discussing these alternative and we will face and win this challenge as in the past.”

He also said the question of a possible economic collapse was coming from 2006 and it was not something new. “This has been repeatedly said and this is said with a political angle. But there are some issues though these critics will never come up with any solutions.”

With the shortage of dollar inflows, similar to Lebanon, Sri Lanka’s rupee currency has plunged in black market. It was trading around 225 rupees per dollar at the latter part of last week, though the Central Bank’s official data show the inter-bank transactions were done at around 200 rupees.

The large amount of the Government’s revenue is used for debt servicing and for the salaries of a bloated civil service stacked with political appointees. Successive governments have neglected repeated calls for reforms and to rein in the deficit.

Like Lebanon, Sri Lankans also wanted to change the political system and culture which was the reason most of them overwhelmingly voted for President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, a non-career politician.

That move came after people witnessed the plundering of State resources by politicians for decades. People still have some grim hopes that the President can do something to revive this country though their hopes are eroding fast with the Government rapidly losing public trust, mainly because of economic hardships especially in the face of COVID-19.

IMF help for confidence

Though there is speculation that Sri Lanka is also on the path for a sovereign default probably in 2022, some optimists say the island nation’s economic condition has not worsened to a level where Lebanon was just before declaring sovereign debt default.

The Central Bank last month was unable to raise $ 100 million to rollover Sri Lanka Development Bonds (SLDBs) and got only around 36% of what it wanted.

“It is a sad state of affairs, but it is the truth. However much the Government is trying to show the world and the people here that they have enough and more dollars with them and there is no need to panic, the reality is they were scared even to go to the market and raise the amount required to repay this debt,” Harsha De Silva, an Opposition MP and economist told media last week.

“Immediately we have to go for a debt restructuring programme. There is no doubt about that. In order to do that we have to go to the IMF to create that platform to bring everyone together.”

De Silva was a State Minister in the previous Government which went for a $ 1.5 billion IMF loan in 2016. It raised tax revenue and curbed Government expenditure with an aim of fiscal prudence under the IMF loan which instilled global investor confidence.

However, that Government became unpopular for its economic management, partly due to misinformation and fake news campaigns carried out by its main Opposition members, who are now in Government.

The current Government’s stubborn stance of not seeking IMF assistance was reflected in global investor calls held last year.

After presenting the 2021 Budget in November, a State Minister of the Government took part in two global calls with investors to explain the Budget. However, investors and analysts on the call said the Minister was unable to “convincingly respond” to the questions raised over plans for foreign debt repayment.

Rating alarm

Just before the sovereign default, Lebanon was hit with a double downgrade by two of the world’s largest ratings agencies, Moody’s and S&P Global Ratings, dragging its sovereign credit rating further into junk territory. Sri Lanka’s credit rating has been already downgraded two notches by three global rating agencies last year and the rating is already in the junk territory.

After the rating cuts, both Sri Lanka’s Central Bank and Finance Ministry criticised all the rating agencies, charging that the decision had been based on incorrect facts.

Unlike the ousted ‘Good Governance’ administration, the current Government has yet to come up with a comprehensive plan to face the heavy external debt repayment. The Government, however, has said the upcoming Chinese-built Port City could be a game-changer once it commences operations.

Besides this, the ruling Sri Lanka Podujana Party (SLPP) is seriously looking for options to avoid any defaults and the measures include SWAP arrangements with the central banks of China, India, and Bangladesh, leasing out some prime lands in Colombo on a long-term lease, and cultivation of cannabis to export as a medicine.

Fitch Ratings in a 16 June statement said affirmation of Sri Lanka’s ‘CCC’ junk rating reflected a challenging foreign-currency sovereign external debt repayment burden over the medium term, low foreign-exchange reserves and high and rising Government debt that give rise to sustainability risks.

“External liquidity pressures have eased somewhat in recent months following bilateral loan disbursements, and our expectation of a forthcoming IMF special drawing rights (SDR) allocation,” it said.

It said a total of about $ 29 billion in foreign-currency debt obligations were due between now and 2026, against foreign exchange reserves of $ 4.5 billion as of end-April 2021. The Central Bank data showed that the Government has to repay $ 7.2 billion in the 12 months through end April 2022.

The island nation has no option of rolling over the $ 1 billion sovereign bond, maturing this month, but has to pay from the reserves.

Fitch early this month said Sri Lanka’s largest banks were the most susceptible to heightened sovereign risk due to their higher exposure to foreign-currency denominated Government securities and, in some cases, weaker capital positions.

Grappling with pandemic

Before proving his economic policies, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa unfortunately had to deal with an unpreceded pandemic since early last year and it is still uncertain when the country will see the normalcy.

A shrinking economy, excess printing of money, excess local borrowing, higher cost of living despite moderate inflation, depleting foreign reserves, job losses, lack of foreign inflow from tourism and lack of aid from pro-West nations – all indicate that Sri Lanka is yet to come out of a possible default crisis.

“I see many issues in Sri Lanka similar to what happened in Lebanon. However, I do not see any default coming this year,” a London-based financial analyst who has been doing research on Sri Lanka’s external debts said.

“The issue is I still don’t see any concrete statement from the Government on how they are going to face the external debt repayment throughout 2026.”

(The writer is former Reuters Economic Reporter for Sri Lanka and current Head of Training at Center for Investigative Reporting Sri Lanka. He can be reached at [email protected].)

Discover Kapruka, the leading online shopping platform in Sri Lanka, where you can conveniently send Gifts and Flowers to your loved ones for any event including Valentine ’s Day. Explore a wide range of popular Shopping Categories on Kapruka, including Toys, Groceries, Electronics, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Flower Bouquets, Clothing, Watches, Lingerie, Gift Sets and Jewellery. Also if you’re interested in selling with Kapruka, Partner Central by Kapruka is the best solution to start with. Moreover, through Kapruka Global Shop, you can also enjoy the convenience of purchasing products from renowned platforms like Amazon and eBay and have them delivered to Sri Lanka.

Discover Kapruka, the leading online shopping platform in Sri Lanka, where you can conveniently send Gifts and Flowers to your loved ones for any event including Valentine ’s Day. Explore a wide range of popular Shopping Categories on Kapruka, including Toys, Groceries, Electronics, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Flower Bouquets, Clothing, Watches, Lingerie, Gift Sets and Jewellery. Also if you’re interested in selling with Kapruka, Partner Central by Kapruka is the best solution to start with. Moreover, through Kapruka Global Shop, you can also enjoy the convenience of purchasing products from renowned platforms like Amazon and eBay and have them delivered to Sri Lanka.