Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Wednesday, 11 November 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Alongside its devastating impact on the global economy, the COVID-19 pandemic has encouraged a new era of innovative ideas. South Korea’s Universal Basic Income (UBI) experiment is a glimmer of hope in the darkness brought by COVID-19. It is an idea that has become popularised in many other countries, including the USA.

Alongside its devastating impact on the global economy, the COVID-19 pandemic has encouraged a new era of innovative ideas. South Korea’s Universal Basic Income (UBI) experiment is a glimmer of hope in the darkness brought by COVID-19. It is an idea that has become popularised in many other countries, including the USA.

This article provides an overview of the concept and discusses how an experimental level-modified UBI program would boost the post-COVID Sri Lankan economy.

UBI

The key concept of UBI is to provide a basic income to all eligible adults that is sufficient to meet their basic needs. This is provided in the form of a basic living stipend; no questions asked, and this happens in the form of a free cash transfer.

When it comes to how the money is spent, there could be conditions applied. Additional income such as UBI promotes leisure and more spending options, therefore it would result in a stimulated local economy, reduced income inequality, a healthier population, productive use of labour and an improved focus on production and entrepreneurship.

This idea is highly progressive, given the fact that the global trend is moving towards automated industries, which demand less conventional labour and more innovative thinking. Notably, for various reasons, this idea is different from a poverty alleviation subsidy like ‘Samurdhi’.

A UBI program could be used directly as a policy tool, as it broadly influences not only the receivers’ standards of living but also the local economy where the money is spent. Furthermore, participants are not expected to go through a stringent selection process, as eligible adults are entitled to payments, regardless of their current income or any other factors. Overarchingly, inherent issues with current subsidy programs such as political influences become irrelevant.

There are several different UBI models, however, South Korea’s Gyeonggi Pay has been one of the most successful programs in the past.

Gyeonggi Pay UBI experiment

South Korea’s Gyeonggi Province has broken into the limelight with its proposal of an experimental basic income program for young people, to precede the launch of a large-scale program. Under this program, approximately 175,000 24 year-olds receive 900 dollars a year (one million won) with no selection criteria to be met.

The payments are made every three months, in the form of a top-up card. The money must be spent within three months before the next payment is made. Importantly, there is a strict condition; the participants can only spend this money in selected local shops, ensuring that this money lives within the local economy and contributes to supporting it.

For example, they are not permitted to use this money at large international fast-food chains such as McDonald’s or goods of the town next door. At the same time, each transaction is reported to Gyeonggi researchers so allow them to monitor spending trends and household spending patterns continuously. There are also numerous additional surveys being carried out in the background, to observe the overall impact of the program on the local economy.

So far, the results of the experiment seem encouraging, as 80% of the people who responded to the follow-up surveys mentioned that the program encouraged them to visit local shops instead of large supermarket chains. Local shops and restaurants, on the other hand, showed about a 50 per cent increase in sales following the experiment. Overall, the concept so far has enabled Gyeonggi province to have its own stimulated local economy without losing money to the broader economy.

Experiment design in the context of Sri Lanka

To conduct a pilot experiment similar to Gyeonggi Pay, there are certain basic requirements that must be fulfilled by the experiment designers. Utilising advanced technologies, continuous monitoring systems and data collection are all crucial. The advantage of these experiments is that the data could also be reused to help form other policy decisions.

This ongoing learning process helps identify how much money is required to motivate participants towards additional consumption/production that they can then consume/sell back into the market.

When investigating the possible reality of such a project, the writer spoke with a couple of selected candidates from a rural community in Anuradhapura for their thoughts. According to them, programs like this would be more likely to replace non-local products with local substitutes.

They provided a simple example, how will a new market for local herbal drinks be created for conventional tea that is not grown in their area? Meanwhile, some shed light on how the additional income would motivate them to purchase extra seeds and fertiliser to push their boundaries from home gardens to commercial production of their agriculture.

Even though Anuradhapura is a possible geographical niche for a pilot project, selection of an initial geographical area to obtain a proper representation is extremely challenging. This experiment needs to avoid two extremes: (i) highly urban areas with developed markets setup, but with lower levels of production (ii) rural areas that are comprised of self-sufficient agricultural households but with undeveloped markets and shallow market interactions.

Ideally, it demands an area with an adequate balance between production and markets. In such an area, it is expected that households would invest their saved or additional labour into production and stimulate the local economy for higher growth. Sub-urban agricultural areas in the dry zone are ideal candidates for a pilot study. That being said, similar areas in upcountry and Southern parts cannot be excluded.

Most importantly, the selected geographical area should be able to disentangle the allocation of labour and goods between consumption, production and market-based exchange with the additional income. As for the participants, targeting young people initially is an intelligent choice, as this also helps prevent mass movement of productive labourers into cities to undertake relatively unproductive jobs.

Full swing operation, funding and theoretical explanation

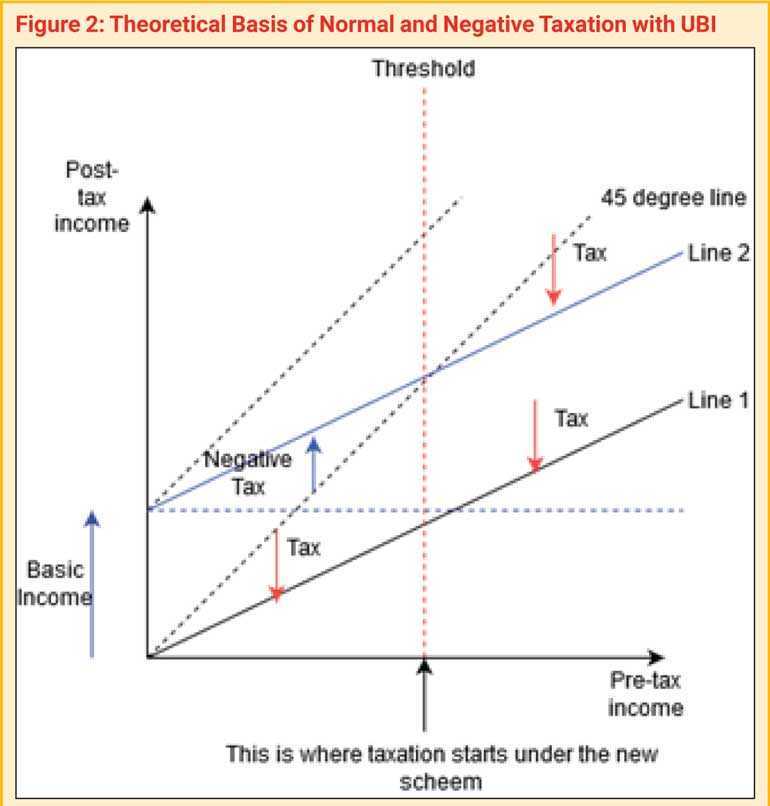

If the pilot project succeeds, policymakers have more incentives to expand the program to the whole of Sri Lanka, perhaps by integrating it with the macro-level fiscal policy. Nobel prize-winning economist Milton Friedman’s negative income tax theory provides a precise theoretical explanation in this regard. Friedman shows that cost of such a stipend could be balanced with a tax system that comprises both positive and negative taxes. Figure 2 shows this basic idea.

However, before moving into a macro-level aggregation, the initial start-up funds need to be raised. In such a case, someone may perceive this as a fiscal expansion, funded through new money that carries the risk of inflation.

However, compared to conventional money-financed fiscal expansions, here, new money is channelled through a guided framework wherein the bottom layer of the economy benefits the most. It could theoretically be shown that such intervention that influences economic growth-centric activities is highly effective.

A recent study by the Roosevelt Institute shows that poor households tend to spend aggressively compared to rich households (see the full study: https://www.econ2.jhu.edu/people/ccarroll/papers/cstwMPC.pdf). In economics, this is measured through Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC). Nevertheless, this disproportional consumption behaviour itself provides the basis for a program like UBI, as funds are injected to the most active part of consumers of the economy. Therefore, UBI is underpinned with the basis for higher economic gains.

Analogically this is similar to starting a fire and attempting to burn larger sized logs. To allow larger sized logs to burn, one must always start with kindling and fine flammable material. Once the fire has started, then it can accelerate and grow. The conventional fiscal expansions ignore the importance of kindling and fine combustible material and attempt to target larger sized logs straight-away, which is not successful in the context of a developing country.

In the same way, this small targeted intervention can be highly productive when compared to conventional and unguided monetary financed fiscal expansion, which can sometimes promote hyperinflation wherein money is not supported by an underlying economic growth.

(The writer is a PhD candidate attached to the Monash University Australia. He is an Engineering graduate from the University of Moratuwa and holds two master’s degrees related to Economics and Finance from the University of New Mexico, USA and the University of California, Berkeley, USA. He previously worked as a Senior Assistant Director at Central Bank of Sri Lanka and as an Operations Analyst at BNP Paribas New York. The writer can be reached via [email protected])

Figure 2 shows Friedman’s basic idea of integrating a UBI program with the tax system. Here, the X axis is the pre-tax income and the Y axis is the post-tax income. The 0 income tax line is shown by the 45-degree line and the normal rate of taxation is shown by Line 1. Now assume everyone is guaranteed a basic income. Line one shifts to Line 2. Now previous income zero person receives the basic income and low-income groups up to the threshold level earn a negative tax (a subsidy). Under the new scheme, the actual normal taxation happens after the threshold. Even though the short term the cost is significant, it is expected that long-term growth prospects will generate more income for the governments. For example, productive labour might generate passive incomes can be utilised by governments in the long term.