Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Friday, 9 March 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

I don’t want you

I don’t want you

But I hate to lose you

You’ve got me in between

The devil and the deep blue sea

– Christopher Rea (song writer)

Volatility of voter behaviour cannot be discounted when election results are analysed for 2010, 2015 and 2018. This is a belated post-mortem of LG elections, due to unavoidable circumstances, nevertheless with a final focus on the present crisis in ‘good’ governance.

Within these eight years, the voter behaviour has fluctuated from one end to the other or between ‘devil and the deep blue sea.’ This is not to blame the voters for any inconsistency, irrationality or opportunism, but to understand the underlying reasons why they behave in such a manner probably given the profound uncertainties in the political economy as a whole.

In 2010, at the presidential elections, Mahinda Rajapaksa (MR) obtained almost 60% of votes while his former Army Commander, Sarath Fonseka left with only 40%. Both were ‘war-winning heroes,’ but perhaps the people trusted more of MR for economic management than a mere Army General. These were the heights of executive presidentialism. MR’s administration managed some economic strides, even during the war years, thanks to the Chinese loans and investments.

When it came to the presidential elections in 2015, not only that the war euphoria had somewhat waned, but the economy also was slowing down without any new initiatives and/or marred with corruption. The voters have a tradition of elected democracy since 1931 and they have effectively changed governments several times since 1956. It was such a change that they particularly wanted in 2015. There was a pressing need for a change given the implications of the 18th Amendment; MR vying for a third term, breaking conventional democratic traditions.

Voter behaviour

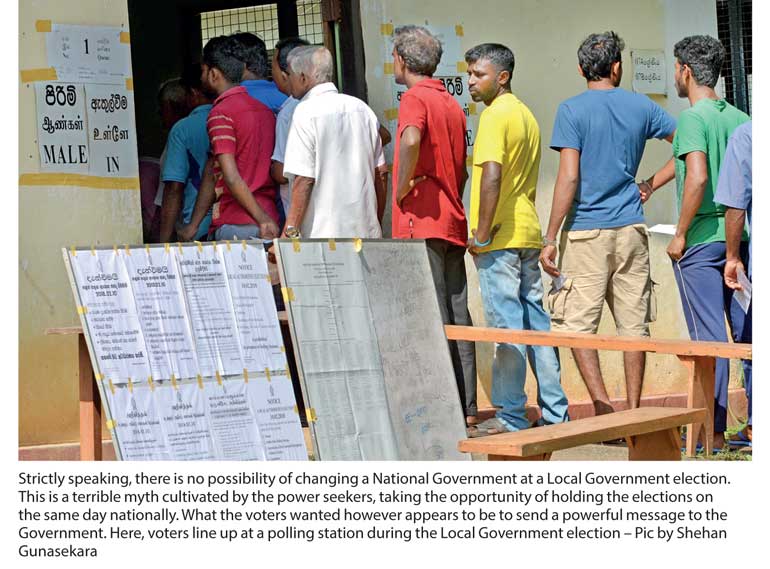

Strictly speaking, there is no possibility of changing a National Government at a Local Government election. This is a terrible myth cultivated by the power seekers, taking the opportunity of holding the elections on the same day nationally. This is a crisis which could have been avoided if the normal procedures of democracy were followed by holding Local Government elections locally and separately.

What the voters wanted however appears to be to send a powerful message to the Government. In addition, it has virtually created a crisis in the Government with attempted changes in the hierarchy. It took five years for the first disillusionment of the voters (2010-2015), and only three for the second (2015-2018).

It is difficult to attribute rationality to individual voters. When they vote, the behaviour could be impulsive also influenced by propaganda. Under modern circumstances, the monopoly of propaganda does not rest with the Government. Even otherwise, the Sri Lankan voters in particular have shown traits of rebelliousness when it comes to disillusionment.

In a fragile, contradictory and uncertain economic circumstances, the disillusionments run quick and high. It is not the rich that determine a voting results at an election, but the poor. When the poor realises that their elected Government is overtly aligning with the rich, national or particularly international, their disillusionments can run a mock. Therefore, the political economy factor stands crucial.

Although the individual voting behaviour might not be counted as rational, the collective voting behaviour is not as such. The voters collectively pass rational messages to the rulers. Otherwise, there is no point in having elections and elected democracy. The failure to take signals would be fatal to the incumbent regimes.

Factors behind

When individuals vote, they do so on the basis of (1) their traditional party affiliations, if there is such, (2) the reliability of the candidate/s, (3) the policies put forward by the parties or the candidates, (4) the attraction or charisma of leaders of the parties, fronts or electoral movements and (5) issues at stake, economic or political. In a country like Sri Lanka, ethnicity, religion and also the general ‘ideological orientation’ do play a role in voting, depending on the voter. That can be considered the sixth factor, but largely working through the previous five.

It appears from various election results of the past that party affiliation is not a long term determinant among voters. There can be some diehard party adherents (kapuvath UNP), but the general voters often change their party affiliations. This is more so in the case of practicing politicians! This can be one reason why the voters also change their parties. Another reason is the fluctuating political fronts, as the individual parties are not confident in winning alone. This has been the case in many elections since 1956.

In the case of the last Local Government elections, the party affiliations became completely overturned. One of the oldest parties in the country, the SLFP, performed extremely poor (4.5%), irrespective of the fact that the President of the country that they elected three years back being the leader of the party. That is a dramatic change.

It is a mindboggling question why did the SLFP put forward candidates under the party name, disregarding a major split within the party, instead of totally contesting under the name of the UPFA (8.9%). The most traditional party in the country, the UNP, also performed quite poorly (32.6%), one of the lowest percentages that they have ever obtained. In contrast, the newly formed party, the SLPP, obtained 44.7% of votes nationally, leading the contest quite spectacularly.

In a Local Government election, what should have become important are the candidates and the local policies, in addition to perhaps political parties. However, none of the parties put forward such local policies and the ballot paper did not give the names of the candidates contesting for a ward. Instead, the voters were asked to select among certain symbols (and the party/group) quite primitively.

Most of the voters did not have a clue to whom they were actually voting. This became hilariously evident at Maharagama, a good number of voters voting for the ‘Motorcycle’ and the candidates being quite unknown to the locals. The voting procedure in fact betrayed the objectives of the so-called new electoral system, boasted as an attempt to deepen democracy by giving the people a true representatives closer to their needs and interests in a ward.

There are criticisms that the Joint Opposition or the SLPP turned the local elections into a national one. Whoever were the advisors, the blame should go to the responsible Minister and the Government for holding Local Government elections nationwide on the same day after repeatedly postponing the elections on the pretext of formulating a new and a better electoral system.

‘Referendum’

In Sri Lanka’s elections and campaigns, there is a certain element of populist mass dynamic. Instead of formal competitions between established political parties, the voters tend to go by emotions, slogans and mere propaganda. This should not be exaggerated however. In such a dynamic, when it happens, what becomes crucially important are the leaders and the issues involved and not so much the parties, the candidates or the policies. Such mass upheavals are often led by (pretentious) charismatic leaders and not the rational ones.

There is much talk about the efficacy of ‘single issue campaigns’ in certain intellectual quarters. It is argued that the ousting of the previous regime was effected on the basis of such a single issue: changing the presidential system. If that was the case that was also the major weakness of that change or campaign. That may be the subjective intention of some campaigners, in particular from the civil society or the left. However that does not appear to be the sole reason why the voters voted for a change in 2015.

If there was a ‘single issue’ that predominated an election campaign in the recent past, then that was at the last Local Government elections. Perhaps the opposition learned it from the Government strategists. The opposition called for a ‘referendum.’ It was the single issue: ‘whether the people have confidence in the Government or not.’ Although the opposition that called for the ‘referendum’ did not strictly obtained over 50% vote, to fulfil a formal referendum, nevertheless the result was overwhelmingly against the Government.

Crisis in local governance

There are crises in governance at two levels. What is most neglected is the crisis in the Local Government system. The other is within the Cabinet and in the UNP-SLFP ‘National Unity’ Government. Both are the creations of the politicians and not the voters or the people. What is revealed at the Local Government elections is not only the political culture or behaviour of the voters, but mostly of the politicians.

Sri Lanka has had the most disastrous Local Government reform last year, under the patronage of ‘good governance,’ and the crisis that the country is experiencing now is largely due to this irrational reform. This was also after three years of procrastination. No country has ever doubled the number of councillors in Local Government institutions in one stroke like in Sri Lanka. It is said that the number of councillors in some councils in fact exceeds the number of workers employed by the council.

Even after almost a month of the elections held on 10 February, the authorities have not yet been able to officially constitute the councils. There are now efforts to disregard the women representation at least in some councils, on various pretexts, without admitting the flawed procedures or rectifying them without delay. Even after the final constitution of the local councils, it is likely to have the most antagonistic and thus a dysfunctional system quite detrimental to the needs of the local populous.

This is a mammoth tragedy considering that the indigenous Local Government system or Gamsabhas have a long history in the country. This is also a major failure of ‘good governance’ or Yahapalanaya that the present Government is elected on.

Crisis in the ‘National’ Government

The crisis in the ‘national’ or the ‘National Unity’ Government is not merely a result of the recent local elections. The verdict of the people has just aggravated it. There are many interpretations given, pseudo-constitutional and other, to the present crisis and what is mostly neglected is the policy aspects and crises.

From the beginning, the Government did not appear to follow the basic principles of parliamentary democracy, for example, in dismissing the previous PM, and in appointing the new one in January 2015. This was the same in the case of ousting the then incumbent Chief Justice and appointing a new one or the previous one. The Government appeared to put forward a theory that ‘good governance may be achieved through bad governance or authoritarian principles.’

Although the governmental change created a considerable space for ‘free speech’ and political activity, soon came the ‘bond scam’ within a month quite negating the anti-corruption drive that it promised to the people. The main defender from the beginning of this corruption was the Prime Minister, Ranil Wickremesinghe (RW), himself who was politically responsible for the initial and subsequent corrupt practices.

It is difficult to fathom how any ‘good governance advocate’ could defend this man, unless he/she is tainted with the same ailment. This was also the reason why the UNF could not obtain a clear majority at the general elections in August 2015, even though at that time the full details and gravity of the corruption were not clear. The people were baffled without a proper alternative.