Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday, 4 October 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

RBM guides all management activities towards the ultimate achievement of defined results at its core

The main objective of this short essay is to explore the basic concepts and approaches of the Results-Based Management (RBM) system. I also wish to discuss its uses in development results, the challenges of results-based management systems, and its impact on output and outcome.

The main objective of this short essay is to explore the basic concepts and approaches of the Results-Based Management (RBM) system. I also wish to discuss its uses in development results, the challenges of results-based management systems, and its impact on output and outcome.

It is essential to assess efficiency and effectiveness through organisational learning, accountability, and performance monitoring and evaluation in this context. Although results-based management is an aspect of new public management, many different terms are often used while searching for RBM. The equivalents of the same model found in the literature is management by results, performance management, rational management, development cooperation, and effects of management practices. However, herein RBM will be used for simplicity.

The core of the process

RBM emphasises the importance of defining expected results with the involvement of key stakeholders, assessing the risks that may impede anticipated results, monitoring programs designed to achieve these results through the use of appropriate indicators that report on performance. A ‘result-chain’ is at the core of this process: human and financial resources (inputs) generate activities that produce results in the short term (outputs), as well as in the medium, end-of-project, term (outcomes); and in the long term (impacts).

Therefore, RBM guides all management activities towards the ultimate achievement of defined results at its core. It represents a fundamental reorientation away from previous management approaches dominated by an emphasis on inputs and activities. It is presumed that results would follow if the inputs and activities were made appropriately dynamic.

In RBM, management functions consist of planning, organising, leading, and controlling, focusing on achieving performance targets. Arif, Jubair, and Ahsan (2015) discussed that RBM is one of the excellent management systems in which all efforts focus on optimum result achievement under the basis of norms of good governance. They have further pointed out that RBM’s framework results in better findings than this moment’s monitoring practice executed in public sectors. RBM’s framework monitors project purpose directly, which is in line with long-term purpose assessment.

Meanwhile, different scholars have identified that RBM effectively increases performance as demonstrated by customer care, meeting performance targets, and producing qualified products. It shows that the RBM implementation may hold organisational performance.

Several deliberations indicate that the RBM sets a platform for determining management policy thinking from a policy-making line in an organisation. Human resources would be a crucial factor in adopting performance standards and implementing the performance-based budget in institutions. Also, to successfully implement performance-based assessment, RBM would consider organisational competence and commitment at all organisational levels. It is crucial to have a new financial accountancy system and management policy, competent human resource management, and continuous drive and support from an organisation.

The puzzle in outputs and outcomes

This article’s core discussion on RBM is to apply output and outcome in our work, projects, initiatives, etc. It outlines the concepts of RBM and how we are capitalising on outputs and outcomes. In study encounters, outputs and outcomes do have a simple connotation. Outputs, outcomes, and impact are terms used to describe changes at different levels. As illustrated in the preceding discussion, outputs are the products, goods, and services that result from a development intervention. These projects are for producing outcomes – the short-to-medium-term effects of an intervention – and eventually impacts.

It is evident, however, that there is a significant inconsistency in the interpretation of these concepts. As per OECD’s (2011) definitions of the different terms when it comes to RBM in development cooperation, the explanations are as follows;

Input: The financial, human, and material resources used for the development intervention.

Activity: Actions taken or work performed through inputs, such as funds, technical assistance, and other types of resources mobilised to produce specific outputs (Related term: development intervention).

Output: The products, capital goods, and services that result from a development intervention; may also include changes from the intervention relevant to the achievement of outcomes.

Outcome: The likely or achieved short-term and medium-term effects of an intervention’s outputs.

Impact: Positive and negative, primary and secondary long-term effects produced by a development intervention, directly or indirectly, intended or unintended.”

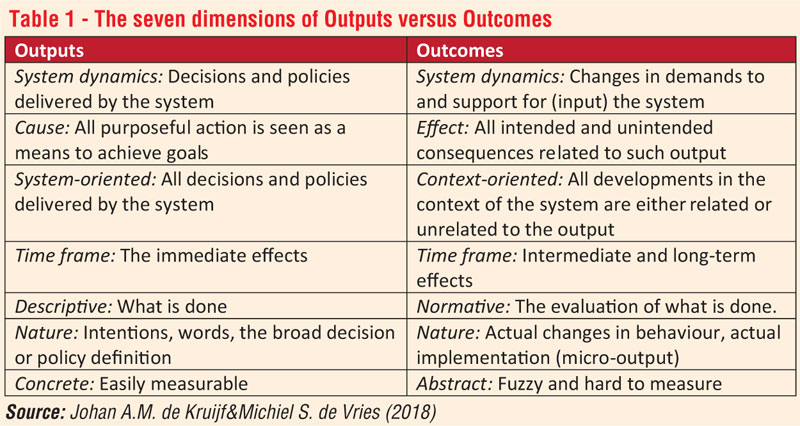

According to the problem, ‘output’ and ‘outcome’ are abstract terms and vary in meaning. It tends to see both outputs and outcomes as impacts of policies and decisions and take their importance for granted. However, researchers use the terms results, consequences, and outcomes interchangeably. Three terms describe the effects of a program or activity, particularly its achievement or progress toward established goals. In most cases, outputs and outcomes have been explicitly distinguished. Table 1 provides greater clarity of the two.

Impact of outputs and outcomes

The definition of goals has significant clarity-issues, mainly on the premise that goals, in general, cannot be achieved. It is necessary to define measurable goals, to be able to measure results, a habit that has been a subject of criticism. One of the possible implications of only setting measurable goals is the risk of avoiding defining goals that are difficult to measure. As Talbot (2007) puts it, we make essential what can be measured because we cannot calculate what is vital.

Focusing on the process instead of concentrating on the performance and results can lead to validity issues. If defined indicators do not measure the change that is supposed to be measured, the implications of such a shift would be the risk of the gauges becoming the organisation’s real goals instead of indicators that correlate with the higher-level goal. Hence, there is an inherent risk of missing unintended consequences since the evaluation will only shed light on the pre-set measures.

The popular idea of what can’t be measured will lead to organisations adapting their activities to be measured. For instance, authorities may change their priorities towards less urgent operations in a hospital to keep the waiting time down.

In the public sector, measurable goals are political goals that are complex and difficult to operationalise, and they lack quantifiability. In such circumstances, there is a significant risk that these measurable goals create a more short-term focus. The general public appoints political leaders for a specific term, and the natural trend is that it is for a political cycle (Specific period unless otherwise changed). The politicians wish to achieve the goals set up within that period. In the RBM debates, this political cycle issue is an attribution problem. It connects to the subject of the availability of information from one cycle to the next cycle.

On the one hand, there is a risk that the pressure on presenting results and statistics about a specific period will increase the need for such data and functional data systems in a particular context. On the other hand, all the information created must showcase what outputs and outcomes are produced from a specific project. It could get transmitted to the next phase where the other party or new leadership can interpret nature differently, as it’s a general phenomenon on the political front.

RBM at critical times

Critical times demand decisive decisions. Decisions are actions. Results-based management is a management strategy, or a set of management principles, aimed at achieving essential changes in the way organisations operate, with improved results as the central orientation. The primary purpose of this thinking and practicing model is to improve efficiency and effectiveness through organisational learning and, secondly, to fulfil accountability obligations through performance reporting. It also underscores control over outputs, which creates a need for measuring performance through regular follow-up, evaluations, and audits.

Ideally, one of the basic assumptions is that politics and administration should separate, as they have different agendas. However, one can’t execute without the blessings of leadership. Once the goals formulate, it is up to the executing power to shape the operations towards reaching the goals by achieving objectives.

Management by Objectives uses the term ‘objective,’ but the question remains whether that term adequately defines the concept? With RBM, the terms inputs, activities, outputs, short-term outcomes, medium-term outcomes, and long-term impacts are well-defined, and they carry specific and different meanings. Thus, RBM creates a more significant focus shift for the future, inviting us to be more practical in our endeavours. We prefer to discuss problems and analyses of the situation in detail. We hardly look at the results in a systematic way and work out backward for genuinely effective results. It is that the RBM model aims at producing results at all times. We see some initiatives but not results!

(The writer is a Faculty Member/Management Consultant, Postgraduate Institute of Management, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka. He can be reached via [email protected].)