Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Tuesday, 16 April 2024 01:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The largest recipient of the gross income of banks happens to be depositors and creditors who have invested in the debentures issued by banks

The largest recipient of the gross income of banks happens to be depositors and creditors who have invested in the debentures issued by banks

The actual distribution of banks’ income shows that the major beneficiaries have been not the shareholders, but depositors, employees, other service providers, delinquent customers, and the government. All these categories together account for about 90% of banks’ income and only about 10% is left for shareholders. Hence, the wide-spread belief that banks fatten themselves at the expense of customers is not supported by evidence

Banks should make profits to rescue themselves

Banks should make profits to rescue themselves

A reader of the Part I of this article (available at: https://www.ft.lk/columns/Debate-over-profits-of-banks-Who-shares-them-ultimately/4-760400) has brought to my notice that banks should make profits, in addition to the reasons mentioned earlier, to support them when they are financially insolvent.

This argument has validity in the current legal context in Sri Lanka. It is the accepted policy of the Parliamentarians in Sri Lanka, as revealed in the new Central Bank Act and the Banking (Special Provisions) Act that when banks get into insolvency, they should not be rescued through printing of new money by the Central Bank. Section 6 of the Central Bank Act has stipulated that the primary objective of the bank is to achieve and maintain ‘domestic price stability’ and ‘the other objective’ shall be to secure ‘financial system stability’.

This is starkly different from the previous Monetary Law Act in which both economic and price stability and the financial system stability had been made co-objectives of the bank. In the present case, the Central Bank will pursue the first as its primary objective and do something to secure the system stability if it does not conflict with the first objective. This ‘something’ relates to securing the stability of the system as a whole, known as macroprudential financial regulation of banks, and not the protection of individual banks as a consumer protection measure. Accordingly, the Parliamentarians have decided that the protection of individual banks, if they become insolvent, should be the responsibility of the taxpayers. Since, under this macroprudential policy, in terms of Section 66, the Central Bank can mandate banks to maintain different types of capital requirements, they should necessarily make profits to meet those additional capital ratios.

Exclusive authority to resolve insolvent banks

According to Section 62 of the Central Bank Act, the bank should be the exclusive authority to resolve insolvent banks under its supervision and regulation. It should consult the Minister of Finance only if the taxpayers’ moneys are used to resolve such a bank. When public funds are used for this purpose, the procedure is known as ‘bailing-out’ of insolvent banks by outsiders.

There is a consensus, after the frustrating experiences of the global financial crisis of 2007-8, that the burden of bailing out a bank should not be passed on to the taxpayers and banks should have their own means of coming  out of a general insolvency situation. This is called ‘bailing-in’ of banks by those who have an interest in the bank from within, namely, shareholders, depositors, creditors, and sometimes, employees.

out of a general insolvency situation. This is called ‘bailing-in’ of banks by those who have an interest in the bank from within, namely, shareholders, depositors, creditors, and sometimes, employees.

As a prelude to bailing-in of banks, the Section 9 of the Banking (Special Provisions) Act has mandated all banks to prepare a recovery plan, also known in banking circles as a resolution plan or a living will. This section has further stipulated that the bank concerned should not rely on, in any manner, funds from the taxpayers to recover from insolvency. Hence, funds should necessarily be generated internally.

In addition, in terms of Section 11, the Central Bank should design a resolution plan for systemically important banks based on the information supplied by such banks. Section 34 permits the government to provide capital to a systemically important bank being resolved but that will be a very rare occasion under the current condition of severe budgetary constraints faced by the government. The Central Bank has been taken out of the scene by Parliamentarians when it comes to providing capital funds to an insolvent bank. Section 36 of the Central Bank Act has permitted it to lend under exceptional circumstances only liquidity financing for 91 days, on the pledge of securities, and the extension of same for further 91 days if the need arises. Hence, banks are now on their own. They should build the capacity to stand on their feet without passing a cost to depositors by earning enough profits.

Who has used the income of banks?

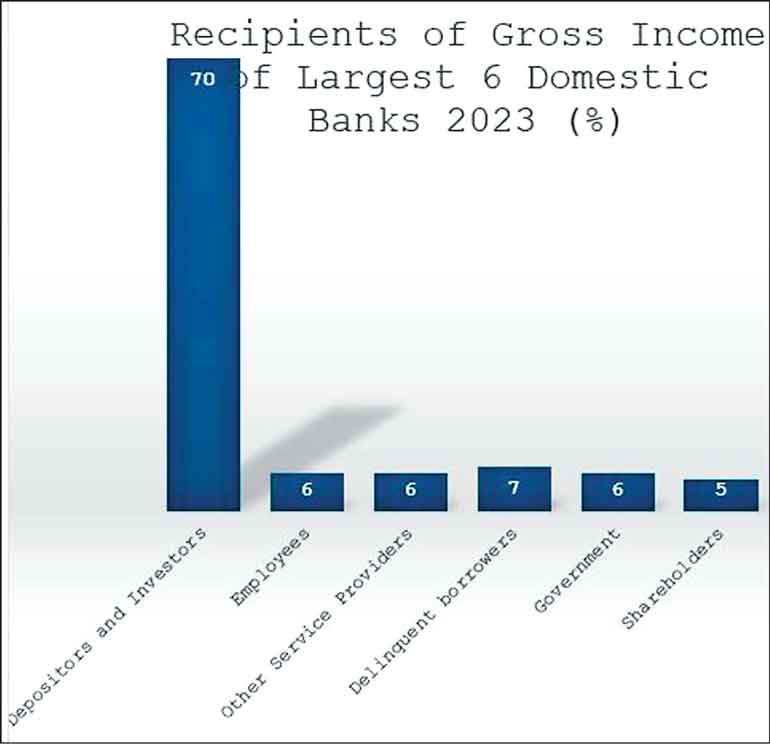

It is therefore important to identify where the incomes of banks have gone. I have calculated the recipients of the gross income of banks for the largest 6 domestic banks in 2023 from the published data. The results are given in figure I.

Depositors are the largest recipients

Accordingly, the largest recipient of the gross income of banks happens to be depositors and creditors who have invested in the debentures issued by banks. That amounts on average to 70%. However, the two state banks had paid more than 80% and the share has fallen to 70% due to the payout of about 60% by the other four domestic banks. The average for the six banks is in line with the published data by the Central Bank in its Financial Stability Report for 2023. Accordingly, on average, during the first 9 months of the year, commercial banks, as a group, have paid about 74% of their total income to depositors and other fund suppliers. This is contrary to the popular belief that banks are paying a pittance to their depositors compared to the thumping interest income they have received.

However, the Central Bank’s Stability Report mentioned above has reported that the interest margin, on average in commercial banks, had been only 3.6% in the period under reference. This is a substantial decline in the interest margins of 1990s that amounted, on average, to about 6%. However, Sri Lanka’s interest margins are not the optimal in comparison to global best records. For instance, in Singapore where there is an efficient banking sector due to its exposure to global competition, the net interest margins are around 1-1.5%. In 2024, due to the extraordinary condition of high interest rates, it is expected to peak at 2%. What this means is that Sri Lankan banks should continue their push for increased productivity which in turn will reduce the net interest margins.

Share of employees and other service providers

Both employees and other service providers had appropriated 6% each of the total income. This is prior to any salary adjustment on account of increased cost of living in the country. Since interest rates also have fallen due to the relaxed monetary policy stance of the central bank, once these rates are adjusted upward, these two categories will account for a bigger share of the total income of banks. This requires banks to improve labour productivity via automation and employment of advanced technologies.

Delinquent borrowers

During the economic crisis of 2021-2, there has been a significant increase in the incidence of loan default by borrowers, The Central Bank Financial Stability Report for 2023 has reported that the allocation for loan impairment in this manner happened to be about 22% of the total income of banks in 2022. However, after peaking of the loan impairment ratio, in 2023, it has moderated to about 7% of the total income. However, this ratio might increase again if the current economic crisis is not resolved in the next few years.

Heavily taxed banking sector

Banking industry has been a major contributor to the government coffers. It does so through taxes. Banking firms are taxed by the government at two stages: first at the income generating stage as value added taxes at 18% and social security contributions at 2.5% and then, at the profit ascertainment stage, as corporate income taxes at 30%. Value added tax and the social security contributions being indirect taxes could in principle be passed by banks to their customers. Yet, these taxes are fully borne by banks. The amount paid to government as a share of the gross income in 2023 amounted to 6%. However, the taxes paid on net income before taxes of these six banks had amounted to a thumping rate of 69%, which cannot be justified by any tax standard. Further, these taxes have reduced the shareholders’ value by more than a half from Rs. 209 billion to Rs. 100 billion. A country which expects its banks to stand on their own feet when resolving insolvent banks cannot squeeze their resources to the bottom of the bowl in this manner.

Shareholders don’t get the lion’s share

After paying all these payments, the amount left for shareholders happen to be only 5% of the total income. Hence, it is not accurate that the banks have been overcharging customers and underpaying depositors to satisfy the shareholders. In the new banking environment, it is the shareholders who should ‘bail-in’ insolvent banks. But if the profits left after paying all these payments are insignificant, the capacity of shareholders to bail-in an insolvent bank is limited.

Role of banks

Banks provide a useful service to the economy and without them, the modern money economy cannot function properly. Banks help both savers and lenders. They mobilise scattered savings at a lower cost, pool such funds and make available those funds to investors by way of short-term and long-term loans. Short-term loans that provide working capital help the economy to maintain the current production and employment levels. Long-term loans that provide investment capital help the economy to expand the production boundary and, hence, generate economic growth. They also pool risks and offer numerous financial products and derivative products to meet every requirement of participants in a modern economy. Yet, banks are always being criticised by the very same customers who are being helped by banks.

Several reasons can be attributed to this animosity against banks.

Need for an amicable public relationship

First, they are big, wield enormous powers and have the right to grant or deny a facility to a customer. Hence, it is natural for a bank customer to feel inadequate when dealing with what he considers as a mighty institution. It leads to what economists call a ‘love and hate’ relationship between banks and customers. They love banks because the banks help them to procure financial assistance to run businesses. They hate banks because they are big and could decide on their future at banks’ discretion. An inevitable corollary of this love and hate relationship is the general suspicion which customers start harbouring in them about every action taken by banks.

Source: Computed by author from published data

Some actions may be genuine and well-intentioned. Yet, the normal suspicion about banks does not help customers to fully appreciate what banks have done for them. It applies to the profits made by banks which in the eyes of customers would have been possible only if banks had exploited the customers. This psychological resentment in bank customers against banks comes to light in various forms and one such form is the criticism of banks on the ground of making exorbitant profits or maintaining unfair margins. It is necessary that banks cultivate amicable customer relationships to eliminate such harmful attitudes in the customers.

Maltreatment of customers?

Apart from the unfounded perception of suspicious behaviour of banks, banks’ casual treatment of customers too has contributed to a wide-spread mistrust about banks’ actions and policies. There is ample evidence about banks’ not properly disclosing full information when they enter a contractual arrangement with a customer. One example is how a bank would treat a customer who wishes to make an early repayment of a loan. Genuine customers who do not wish to get into indebtedness might want to repay their loans earlier than the maturity date. For them, having a loan liability is some unbearable burden and would like to have them discharged from it as quickly as possible. However, banks, as a general policy, discourage early repayment of loans before the contractually due date.

It is not difficult to understand the logic employed by banks in such cases. Early repayment distorts the bank’s targeted cash flow and interest income. Hence, any early repayment is made subject to penal rates making it costly for a borrower to exercise that option. To be fair by banks, these conditions are printed in loan agreements what some people refer to as ‘small prints’ But they are not properly explained to customers when the agreements are signed and they come to know about it only when they plan to make an early settlement of a loan.

Asymmetric adjustment of rates

Another maltreatment which customers often complain about is the one way revision of interest rates by banks when the market rates have increased. This often happens when loans are raised against the security of fixed deposits. In this type of loans, the customer initially agrees to pay interest on the loan at a rate certain fixed percentage points higher than the rate paid on the fixed deposit. However, when the market rates rise, banks unilaterally raise the rate charged on the loan without making a corresponding rate revision on the secured fixed deposit. Banks empower themselves to do so by incorporating permissive clauses in the loan agreements. Such clauses too are not fully explained to the customers at the time of signing the loan agreements.

Injurious perceptions

These incidents may occur in isolation but add one by one and gradually to the general adverse perception which customers form about banks. They spread quickly across the market by word of mouth or by deliberate publicity given in the media. Such perceptions are injurious to the healthy operation of banks. It, therefore, calls on banks to have proper and effective customer management systems established within banks. Such customer management is as important as the normal asset and liability management techniques which banks piously adopt as risk mitigation devices.

Need for profits

Banks must make profits to ensure their sustenance as going concerns. However, such profits which are glorified by banks themselves have become the source of public resentment against banks. The normal belief by many has been that banks make profits at the expense of their customers. In other words, many believe that banks overcharge customers and, in the process, do exploit them. This argument suggests that banks’ shareholders enrich themselves by continuously exploiting their most valuable asset, viz., the customer base.

Users of bank incomes

However, the actual distribution of banks’ income shows that the major beneficiaries have been not the shareholders, but depositors, employees, other service providers, delinquent customers, and the government. All these categories together account for about 90% of banks’ income and only about 10% is left for shareholders. Hence, the wide-spread belief that banks fatten themselves at the expense of customers is not supported by evidence.

Put a stop to maligned public opinions

The public forms adverse perceptions about banks because of what they believe as maltreatment at the hands of mighty banks. Banks themselves are responsible for this harmful but avoidable opinion formation. Such adverse public perceptions can easily be avoided by establishing proper and effective customer management systems in banks. Banks should realise that effective customer management is as important as the normal asset and liability management which they employ as a part and parcel of their day-to-day management.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)