Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Wednesday, 17 October 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka’s excessive reliance on foreign capital to finance investment under favourable external financial conditions is now leading to disruptions, as those conditions change in a decisive interest rate tightening phase in the United States. As US monetary policy becomes tighter and the dollar strengthens, emerging economies like Sri Lanka are hit by twin blows from both the interest rate and currency adjustments.

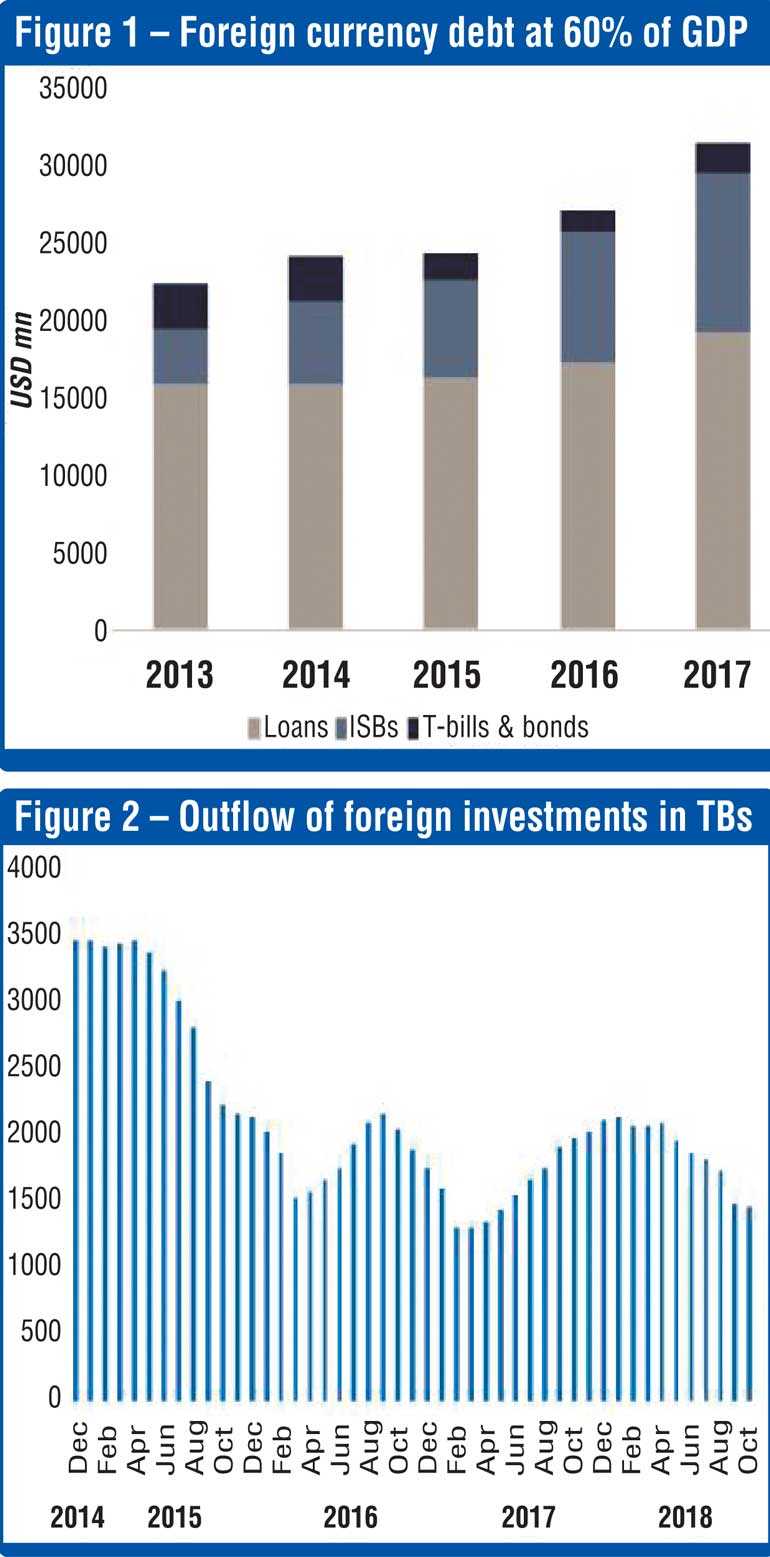

The Sri Lankan rupee (LKR) has depreciated by 10% in nominal terms by end September 2018, relative to a 2% depreciation in 2017. Sri Lanka is not alone amongst emerging economies; in fact, it can be argued that the depreciation of the LKR looks modest next to the near 14% depreciation of the Indian rupee. But that is where the comparison ends, because Sri Lanka, unlike India, is carrying a hefty total external debt stock at 60% of GDP that makes the economy-wide impacts of currency depreciation far more risky.

The Sri Lankan rupee (LKR) has depreciated by 10% in nominal terms by end September 2018, relative to a 2% depreciation in 2017. Sri Lanka is not alone amongst emerging economies; in fact, it can be argued that the depreciation of the LKR looks modest next to the near 14% depreciation of the Indian rupee. But that is where the comparison ends, because Sri Lanka, unlike India, is carrying a hefty total external debt stock at 60% of GDP that makes the economy-wide impacts of currency depreciation far more risky.

The current vulnerability of the LKR comes primarily from a reversal of capital flows, although an upswing in international oil prices and consumer imports on vehicles added to pressures in the thin forex market. The Central Bank of Sri Lanka’s (CBSL) sensible approach to allow a gradual depreciation to take effect, with some limited intervention to defend the LKR has, however, come under mounting criticism. This is not surprising perhaps, given that Sri Lanka is more used to delaying the inevitable, by using up the last of its official reserves before a forced, and often sharp, devaluation is affected.

Thus, unlike the two most such recent episodes in 2015 and 2012, a more pragmatic and prudent stance is being implemented. With reserves down from $ 10 billion (5.5 imports months) in April 2018, to $ 7.2 billion (4 import months) by end September 2018, policy interventions at hand for Sri Lanka have dwindled owing to past and current dollar denominated borrowing.

Brakes on non-essential imports and measures to induce repatriation of export earnings aside, what can work is temporary capital controls on outflows as successfully applied by Malaysia during the East Asian financial crisis. But here too, Sri Lanka comes up against the need to retain foreign investor confidence as it prepares to refinance a large volume of foreign debt settlements during 2019-2022.

And there lies the economy-wide threats to the Sri Lankan economy from the currency turmoil. Debt measured in LKR will balloon; more so, if GDP growth remains at the rather modest 4% seen in the last six consecutive quarters. Strong growth is important to lower Sri Lanka’s debt leverage ratios.

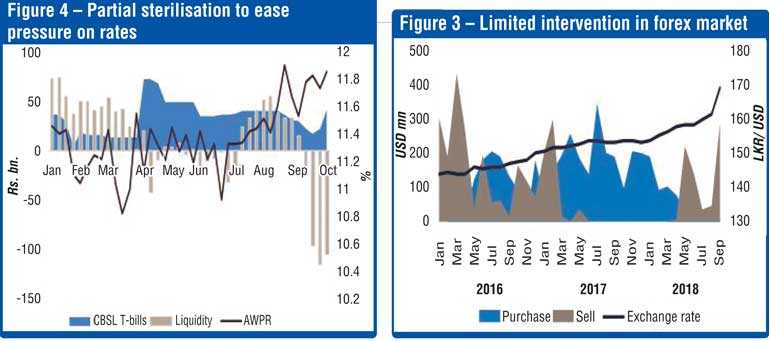

The role for fiscal policy is limited. To dispel foreign investor concerns and ensure that confidence is upheld, a sustainable fiscal regime is necessary. Already, the reversal of foreign investments from Treasury bills and bonds, and brakes on imports will impact revenues, while interest servicing costs are likely to nudge up. It seems, therefore, sensible to do what the CBSL has been doing so far – allow for only partial sterilisation of forex market intervention to ensure that interest rates do not go sky-high and stifle private investment and growth prospects altogether.

Non-sterilised intervention in the forex market not only employs the interest rate channel to nudge short term interest rates, but it also sends signals of monetary authority intentions to shape expectations on future monetary and forex policy. But, any leeway here too will come up against rising inflation as depreciation (and fuel price adjustments) feeds into prices; already, year-on-year inflation has climbed from 1.6% in April 2018 to 5.1% in August 2018.

The Sri Lankan economy is thus set to face testing times; dollar revenues need to be generated to match dollar-denominated debt service as never before, just as the next steps and their outcomes for the economy are likely to be heavily determined by the intersection of politics and economics in the country.

(The writer is the Executive Director at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To talk to the author, email [email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ – http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/.)