Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Tuesday, 7 March 2023 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It was wrong of the EC to unilaterally declare elections without reporting to the Parliament about the fiscal situation conveyed to the EC by the Executive – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

The feeble attempts by the Election Commission (EC) in face of resistance from the Government to hold local elections and the awkward missteps that followed have brought two critical issues to the fore.

The feeble attempts by the Election Commission (EC) in face of resistance from the Government to hold local elections and the awkward missteps that followed have brought two critical issues to the fore.

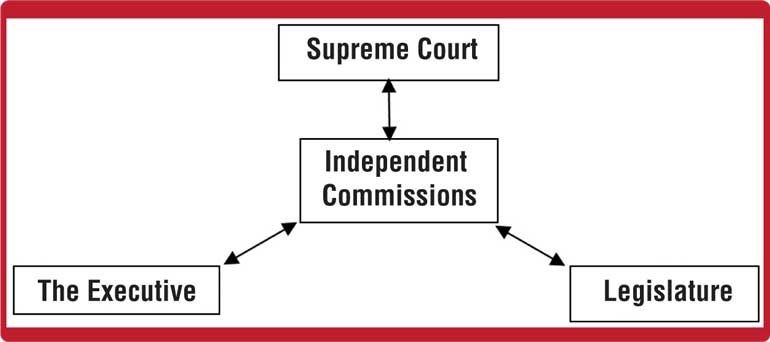

What are limits to the independence of independent commissions? Did the EC overestimate its independence and act unilaterally?

Has the Parliament shirked in its duty as per Article 158 where it states that the Parliament shall have full control over public finance?

There is an uproar in the media and on the streets by the opposition, trade unions, and others demanding the holding of local elections. The EC has maintained that despite claims of no money by the executive there are indeed ways of managing the money. They have gone to the Supreme Court assuring that they will hold the election according to the law. Missing in this conversation is the main actor, the Parliament, the ultimate authority in fiscal matters and to which the EC is ultimately accountable. EC has been going back and forth to the SC and the media, but not reported to the Parliament the fiscal situation communicated by the Executive. How correct is that?

The Parliament is the authority on fiscal or legislative matters, not the Supreme Court

If I am not mistaken, for the first time in the history of the EC fiscal constraints have hampered it fulfilling its obligations to hold elections on time. It is also the first time that the country is facing an economic crisis of this proportion.

As the President revealed in the Parliament in his “I am not postponing elections, no election to postpone” speech, the Secretary for Finance had informed the EC in December 2022 that money is not available for elections. Correct or not, the executive had made the claim and the response of the EC should have been to inform Parliament that its local elections law may not be enforceable and sought guidance.

Yet on 9 February in response to two writ applications filed by groups of parliamentarians in the Supreme Court, the EC had given assurances to the Supreme Court that they will hold the elections as per the law. Did the EC act with due diligence when the Executive had made it clear that money is not available? Various moves by the Executive to drive the message home were ugly to say the least. But that does not absolve the EC from its failure to inform Parliament and seek a resolution to the Executive’s claims. The Parliament is the authority with mandate and the capacity to examine the Executive’s claims and determine whether an unprecedented economic crisis and resulting cash flow problems warrant any legislative action such as extending the term of the local councils.

The general public may have lost trust in Parliament where SLPP, which may not be keen to go to polls, is in the majority. But as far as the EC is concerned, the first stop should be the Parliament no matter who holds power there.

In a decision on 24 February, the Supreme Courts gave itself ample time to make a ruling on an application to postpone the election by setting the next hearing to 11 May and giving time to the Ministry of Finance to explain why they don’t have money. At the same time the Court made the cautionary observation that they could do very little in regard to fiscal matters. The Courts probably expect the fiscal matters to be settled by or before 11 May by Parliament.

Now the ball is in Parliament. What could/should it do?

It is not too late for the Parliament to intervene

It is not too late for the Parliament to intervene

To my knowledge, we don’t have a precedence of fiscal issues directly impacting the functioning of an Independent Commission. The fact of the matter is that the financial crisis has reduced this country to no better than a small private bus operator who would use the daily cash haul to pump diesel for the next day. Unfortunately, the Government has not done a good job of explaining this simple fact to the people.

As Samarajiva noted in his “Does the government have money” column, the cash flow problems have always been there. The appropriation bill is only an estimate for the whole year. If the Government estimated a revenue of 3,000 billion and allocated 10 billion for the election that does not mean that it has the money on hand in February to pay for immediate costs like printing and transport.

In the heydays before the reality of debt default hit us, Government borrowed from the Central Bank getting it to print money, or borrowed from lenders, local and foreign.

Today we have a different scenario. Nobody is lending to us because on 12 April we had to suspend payments on all foreign debt, conclusively demonstrating to the whole world that we are not able meet debt obligations. If we are to become acceptable to lenders again we need a ‘certification’ from IMF to the effect. They will not give that unless, amongst other things, we bring our primary deficit, or the difference between government income and expenditure, to a prescribed level.

If there is any other way out, the agitators in chief – Sajith Premadasa of SJB or Anura Kumara Dissanayake of NPP – have so far failed to reveal such.

The Executives story that there is no cash is indeed plausible, but it needs to be corroborated because the Executive is certainly not an unbiased participant in the affair of holding or not holding local elections.

In my opinion, it was wrong of the EC to unilaterally declare elections without reporting to the Parliament about the fiscal situation conveyed to the EC by the Executive in December. Further, their assertion to the Courts on 9 February that elections will be held without resolving the fiscal issue is also problematic.

It was reported on 24 February that the EC has finally written to the speaker but unfortunately the speaker’s initial response has been lukewarm. Too much money and man hours have been wasted already preparing for an election. The speaker and the Parliament must be creative in finding a solution. Is there some way to set up a Speaker’s Committee in Parliament as in the UK as a priority or can the public finance committee examine the claims by the Executive in an open and transparent manner and make a determination?

Only Parliament is able to study the cash flow claims of the executive and make a determination. If the Executive’s claims are indeed true then Parliament has to make a determination as to what monthly expenditures to cut.

Salaries and pensions consume 86% of the cash flow each month. Will delaying those payments by a few days get us the cash we need without printing money and jeopardising our chance of getting our economy on track? The Parliament has a responsibility to tell us.

The opposition should be in Parliament checking on the President’s claim that there is no money for elections, not creating havoc in the streets demanding an election.

Lessons for the future

Lessons for the future

It is easy to prescribe a course of action in retrospect. In defence of the EC, we are all on a learning curve here. It is not too late to learn from our mistakes and map out a future course of action.

On hindsight, I would say that– “independent commissions have to work within the limits imposed by all three branches of government, and in the event the Executive’s action or inaction hinders the commission’s duties, it should seek the advice of both the Judiciary and the legislature. Regarding fiscal issues, the Parliament is the ultimate authority. The Supreme Court can do little. Fiscal issues is one area where the Election Commission must not act unilaterally.”

Notwithstanding these fiscal limitations, the EC still has sufficient powers to act independently. But we need to make provisions to address fiscal barriers, if any, to be faced by the EC in the future. We cannot have an Executive fearful of elections making claims that there is no money to hold elections. There has to be checks and balances.

1) There is much room for independence

1) There is much room for independence

The independent commission are clearly not laws unto themselves anywhere in the world but they are able to act independently largely by virtue of their recruitment and dismissal processes.

India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, UK and United States, to cite some countries which are more familiar, all have independent commissions for elections. Singapore is an exception where the election commission is under a ministry. All other commissions are accountable to Parliament and open and transparent recruitment and limited dismissal processes allow members of these Commissions to act independently without fear of reprisals.

For example, in UK, the Electoral Commission was established by Parliament as a body independent of Government but accountable to the Parliament. The Chair of the Electoral Commission and the other Electoral Commissioners are selected through an open recruitment process carried out by the Speaker’s Committee on the Electoral Commission. The procedure for removal of recruited commissioners is not clear but a violation of the comprehensive code conduct for commissioners is cited as grounds for removal.

We too have a recruitment process supervised by the Constitutional Council of Parliament. Once appointed, the Commissioners of the Election Commission, say, cannot be removed except by the process prescribed for removal of judges of the Supreme Court outlined in Section 107(2) of the Constitution.

Except for recent missteps in navigating the unchartered waters of fiscal hindrances, one could say that our Election Commissions have so far acted with a reasonable degree of independence. What can be learnt from recent missteps?

Commissions cannot act unilaterally in financial matters, for example

The behaviour of EC in the past few months points to an over-estimate about their own independence. I will hazard four guesses as to why.

First, the 19th Amendment excluded the EC from accountability to Parliament giving an unwarranted sense of impunity to the Election Commission. The 20th Amendment removed this exemption and decreed that all independent commissions are accountable to the Parliament. Though the EC had maintained that they should be treated as a special category, the 21st Amendment drafters too maintained the equality of commissions. The Election Commission had lodged their protest without success. Perhaps the thinking that they are accountable only to the Supreme Court still lingers in the culture of the Commission.

Secondly, even if the EC was to be accountable to the parliament there is no formal mechanism for the purpose. Only after a message from the Supreme Court that it cannot do much about fiscal affairs did the EC sought a directive from the Parliament.

Thirdly, The EC may have tried to show that they are committed to hold the election no matter what to alleviate any question of legitimacy in their appointment. The present Commission was appointed by a disgraced President who had the power to singlehandedly pick the members, and it is alleged that some members were politically active just prior to their appointment.

Fourthly, there is this notion that our Commissions may lose their independence if they engage with the executive or the legislature directly. The local government election debacle shows that an open dialogue with the Executive and the Legislature by the EC with sensitivity to economic realities would have served the country better.

2) An unprecedented economic crisis demands open dialogue between actors

Not only the EC, sometimes other commissions too act as if they should act in a vacuum removed from socio-economic or politico-economic realities. A case in point is the National Education Commission (NEC). The Yahapalana government of 2015-19 came to power with a clearly stated objective of introducing 13 years of education through an additional vocational track in school, but NEC went on to publish a national policy document in 2016 with no reference to the Government’s intended policy. They missed in their responsibility to critically engage with policies of an incoming government. They simply published a document that was in preparation before the election. It is the same with the present NEC and their national policy document released in 2022. There is no mention of the unprecedented economic crisis and the need to go beyond making wish lists as before.

3) A Speakers Committees in Parliament for the Election Commission is a must

We need a mechanism in place for an independent commission to seek an opinion or a solution from Parliament. In the UK there is speaker’s Committee for the Elections Commission. To quote:

“The Electoral Commission [of UK] is answerable to Parliament via the Speaker’s Committee (established by PPERA 2000). The Commission must submit an annual estimate of income and expenditure to the Committee. The Committee, made up of Members of Parliament, is responsible for answering questions on behalf of the Commission. The Member who takes questions for the Speaker’s Committee is Bridget Phillipson.”

In Sri Lanka’s case, a Standing Order establishing a Speaker’s Committee for Independent Commissions should give the committee a wider mandate which allows the presenting of questions on behalf of any Commission to a relevant parliamentary committee.