Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Thursday, 20 February 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka has the highest literacy rate in the South Asian Region. In Sri Lanka, currently, there is a trend that females are keener on receiving education than males, but when focusing the attention on the prevailing labour market of Sri Lanka, the percentage of males in employment is higher than the females.

In the third quarter of 2018, the labour force participation rate of males is 72.7% while females is only 34%. Out of that, the private sector has the highest number of female employees, which is 35.8% (Sri Lanka Labour Force

Survey, 2015).

Women are more educated than men in Sri Lanka. This has been a growing trend, most stark in higher education. In 2015, 60% of enrolment in state higher education institutions was female, and 68.5% of graduating students were female. Most disciplines currently produce a higher percentage of women graduates with notable exceptions in engineering (21.5% female) and computer science (41.8% female).

Challenges

There are a number of challenges facing public and private sectors to fill the labour shortage in several leading sectors in Sri Lanka. Even though the literacy rate is high, the requested skills are not matching where the industries have demands.

Public sector in Sri Lanka is identified to have an over-concentration of women with arts degrees and is also known to have higher rates of employment in this same sector. With wages in the public sector relatively low compared to the private sector, this over-concentration of women in the sector has become a leading factor in gender inequality and the wage gap in Sri Lanka. In addition, the highest levels of unemployment in Sri Lanka are recorded among women with university degrees (Sri Lanka Labour Force Survey, 2011), with most women degree holders known to be arts graduates (University Grants Commission, 2012).

Out of the total graduates, the majority is females and the majority of them are unemployed and are inactive due to not getting proper employment. The majority have successfully completed their degrees with classes, yet their subject choices have restrained them from getting employment.

So, they should be directed to focus on the current labour market and select subjects that help them in getting a job when they graduate. The combined effect of these demographics make women arts graduates in Sri Lanka one of the most vulnerable groups among Sri Lankan graduates. In addition, the problem of unemployment is most acute among women who are educated (G.C.E Advanced Level and above) (Sri Lanka Labour Force Survey, 2011).

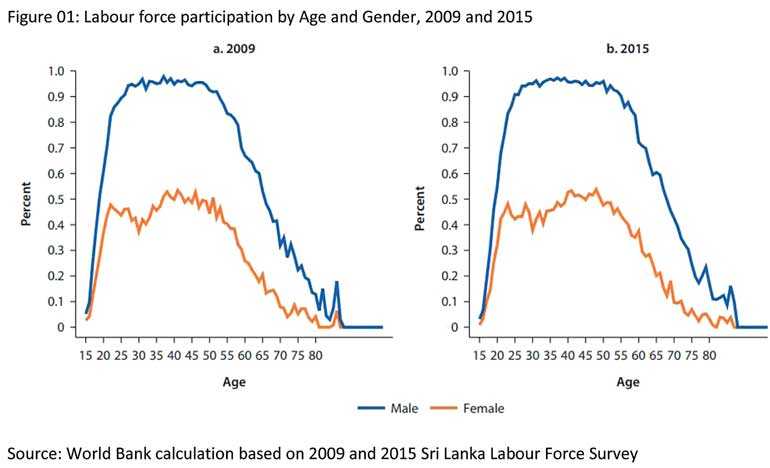

Sri Lanka has the 14th-largest gender gap in labour force participation (LFP) globally (WEF 2016). This large gap is surprising given the country’s long-standing achievements in human development outcomes, such as high levels of female education (including gender parity at most levels) and low total fertility rates, as well as its status as a lower-middle-income country with overall improvements in economic growth of more than 6% annually over the past decade (World Bank 2015, 2016). The World Bank source highlighted the differentiation among female and male labour force participation in

figure 1.

One of the main current issues that bothers the economic development of the country is that the majority of the graduated females are economically inactive. Many factors cause this situation. Women play the key role in handling household activities. Yet their leadership role and dedication towards their families is not recognised by society.

Most of the women claim that they have no time to engage in an employment as they are emotionally and mentally bound to their households. But some women break this social stigma and engage in employments or start their own businesses, but this number is considerably low. This situation prevails among the Arts faculty graduates of Sri Lanka.

The population of Sri Lanka by the end of the 2017 comprises 48.4% male while 51.58% is female. Out of the female population, only 36.6% is engaged in employment and of the 48.4% of the male population, 74.5% participate in the labour force. So, there is a considerable number of females who are economically inactive. Strategies should be initiated to increase the female labour force participation.

Reason for not joining in private sector jobs

Many factors are often influential in the job preference of women arts graduates, making it difficult to identify the effect of one over another. However, identifying and separating these factors as forces that either repulse them out of the private sector or attract them toward the public sector is necessary.

The lack of personal connections that allow access to private sector jobs was found to be the most predominant factor that pushed women arts graduates out of the private sector.

The strongest pull towards the public sector was found to be the policies and work ethics that enabled a healthy work-life balance.

Limited access to private sector jobs, Lower mobility for women that limits the availability of the private sector, and

The lack of skills that are required for the private sector.

Recommendations

Common insights among policy makers and private sector employers is that women arts graduates prefer public sector jobs over private sector jobs even if it means that they would remain unemployed for long periods, and this is often despite having other job opportunities available to them.

This preference appears problematic due to the limited number of jobs available and lower wages in the public sector.

Private sector also expect particular skills from Arts graduates such as, language skills, personality, and leadership, risk handling skills, independence and relevance.

Generally the following recommendations are identified to increase the number of female graduates participating in industry.

Increase female enrolment in ICT technical education by scaling up promotion of STEM courses to girls and their parents. In fact, introducing computer education as a compulsory subject in secondary school, or even earlier, may be the fastest route to ensuring that girls as well as boys are acquiring these important technical skills for their futures.

Expand industry-linked internships and school-based business incubator and exposure programs for female students at the secondary school level.

Provide career counselling and job market information in higher education. A number of school and university -based interventions can be provided to promote increased FLFP in ICT, including internship placements with ICT employers and mentoring relationships with higher-skilled workers and managers (especially female ones).

Awareness programs for the first year and final year female undergraduates of Arts Faculties of the selected universities and connect them with the leading industries and training institutes.

Make aware the female Arts faculty undergraduates of the current labour market and show them the path for future ready workforce.

Ensure the relevance and increase the number of skilled female workforce supply.

Connect the leading industries and institutions with the Arts Faculties of the selected universities.

Reduce barriers to female participation in paid work, particularly lack of child care services and socio-physical constraints on women’s mobility.

Expansion of opportunities for females to access part-time work and maternity leave

Expansion of opportunities for female to generate income in their homes by providing some combination of technical and vocational training, financial literacy and business development training, access to credit or other financial assistance, and links to markets

Improved public transportation safety for women, and create partnerships with private employers to encourage firm-specific transportation for female workers

Expanded housing stock for firms’ female workers (through provision of firm incentives), as well as housing in the vicinity of worksites—for female internal migrant workers and other working women—that is leased at affordable rates

Expectation

By achieving the above mentioned recommendations, the ultimate expectation of this exercise is to increase the female labour force participation and ensure the relevance of the leading employment sectors by encouraging and directing the arts faculty undergraduates to follow a suitable path.

(The writer is Assistant Director, NHRDC.)

References

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/sri-lanka-women-universities/

http://www.wercsl.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Pushed-out-and-Pulled-in-Sri-Lankan-Women-Arts-Graduates-Employment-in-the-Public-Sector.pdf

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/1cfa/43b8c187866b893b3b9af488ff1cefab3f55.pdf

http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/281511510294264126/pdf/121117-PUB-PUBLIC-Getting-to-Work-Unlocking-Womens-Potential-in-Sri-Lankas-Labor-Force-Overview-Ebook.pdf