Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Tuesday, 28 November 2023 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

November is the month to specially remember those who departed. One such important soul draws our attention today. He was born and died in November. To be precise, born on 19 November 1909, and died on 11 November 2005, eight days before his 96th birthday. We are referring to none other than Peter Ferdinand Drucker, one of the greatest management thinkers the world has seen so far. Todays’ column is a tribute to him, 18 years later.

November is the month to specially remember those who departed. One such important soul draws our attention today. He was born and died in November. To be precise, born on 19 November 1909, and died on 11 November 2005, eight days before his 96th birthday. We are referring to none other than Peter Ferdinand Drucker, one of the greatest management thinkers the world has seen so far. Todays’ column is a tribute to him, 18 years later.

Overview

“There are no good or bad institutions but well-managed or ill-managed institutions.” The visionary statement by Drucker is applicable not only to institutions but to countries as well. We have seen that around the globe with, rise and fall of great nations based on the quality of their leadership. “My greatest strength as a consultant is to be ignorant and ask a few questions.” I remember this powerful quote from him, every time I engage in a challenging consultancy. He has been a guiding light for me as a life-long learner.

“Management by objective works – if you know the objectives. Ninety percent of the time you do not.” I have seen the ironic reality of this brilliant quote from him when we set objectives without communicating them properly and promptly to those who are supposed to execute, paving the way for many blame games.

Early days of Drucker

Drucker is acclaimed as the undoubtedly the most influential management thinker of the 20th Century. His career as a writer, consultant and teacher spanned more than six decades. His groundbreaking work turned modern management theory into a serious discipline. He influenced or created nearly every facet of its application, including decentralisation, privatisation, and empowerment, and has coined such terms as the “knowledge worker.”

Born 19 November 1909, in Vienna, Drucker was educated in Austria and England and earned a doctorate from Frankfurt University in 1931. He became a financial reporter for Frankfurter General Anzeiger in Frankfurt, Germany, in 1929, which allowed him to immerse himself in the study of international law, history and finance.

Drucker moved to London in 1933 to escape Hitler’s Germany and took a job as a securities analyst for an insurance firm. Four years later he married Doris Schmitz and the couple departed for the United States. His illustrious contribution to management blossomed during his stay there until his death in November 2005, at the age of 95, at his home in Claremont, California.

Drucker the professional

Business week called Drucker as the man who invented management. His contribution was so vital. He was a professional on many fronts. He shined as a thinker, teacher, and a trailblazer. “Efficiency is doing things right; effectiveness is doing the right things” is perhaps the best yet so simple quote from him.

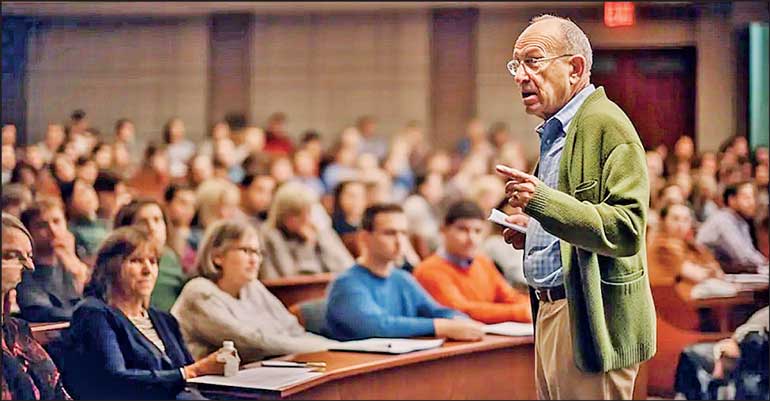

From 1950 to 1971, Drucker was a professor of management at the Graduate Business School of New York University. He was awarded the Presidential Citation, the university’s highest honour. Drucker came to California in 1971, where he was instrumental in the development of one of the country’s first executive MBA programs for working professionals at Claremont Graduate University (then known as Claremont Graduate School). The university’s management school was named the Peter F. Drucker Graduate School of Management in his honour in 1987. He taught his last class at the school in the spring of 2002. His courses consistently attracted the largest number of students of any class offered by the university.

Drucker came to California in 1971, where he was instrumental in the development of one of the country’s first executive MBA programs for working professionals at Claremont Graduate University (then known as Claremont Graduate School). The university’s management school was named the Peter F. Drucker Graduate School of Management in his honour in 1987. He taught his last class at the school in the spring of 2002. His courses consistently attracted the largest number of students of any class offered by the university.

Drucker had long wished to have the name of a benefactor attached to the school that bore his name. His wish was fulfilled in January of 2004, when the name of his friend, Japanese businessman Masatoshi Ito, was added to the school. It is now known as the Peter F. Drucker and Masatoshi Ito Graduate School of Management.

The school adheres to Drucker’s philosophy that management is a liberal art—one that considers not only economics, but also history, social theory, law, and the sciences. As Drucker said, “it deals with people, their values, their growth and development, social structure, the community and even with spiritual concerns… the nature of humankind, good and evil.”

Drucker’s contribution

Drucker’s work had a major influence on modern organisations and their management over the past 60 years. Valued for keen insight and the ability to convey his ideas in popular language, Drucker often set the agenda in management thinking. Central to his philosophy is the view that people are an organisation’s most valuable resource, and that a manager’s job is to prepare and free people to perform.

Drucker’s ideas have been disseminated in his 39 books, which have been translated into more than 30 languages. His works range from 1939’s “The End of the Economic Man” to “Managing in the Next Society” and “A Functioning Society,” both published in 2002 and “The Daily Drucker,” released in 2004. His last book coauthored with Joseph A. Maciariello, “The Effective Executive in Action” was published by Harper Collins in January of 2006.

Drucker created eight series of educational movies based on his management books and 10 online courses on management and business strategy. He was a frequent contributor to magazines and a columnist for the Wall Street Journal from 1975 to 1995. A highly sought-after consultant, Drucker specialised in strategy and policy for both businesses and no-for-profit organisations. He worked with many of the world’s largest corporations, with small and entrepreneurial companies, with nonprofits and with agencies of governments.

“Checking the results of a decision against its expectations shows executives what their strengths are, where they need to improve, and where they lack knowledge or information.” Such was the advice from Drucker for the executives.

Accolades for Drucker

Drucker was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in July 2002 by President George W. Bush in recognition for his work in the field of management. He received honorary doctorates from universities in the United States, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Great Britain, Japan, Spain, and Switzerland.

Let others now speak for Drucker. Given below are some.

“The world knows he was the greatest management thinker of the last century,” Jack Welch, former chairman of General Electric Co. (GE), said after Drucker’s death.

“He was the creator and inventor of modern management,” said management guru Tom Peters. “In the early 1950s, nobody had a tool kit to manage these incredibly complex organisations that had gone out of control. Drucker was the first person to give us a handbook for that.”

Adds Intel Corp. (INTC) co-founder Andrew S. Grove: “Like many philosophers, he spoke in plain language that resonated with ordinary managers. Consequently, simple statements from him have influenced untold numbers of daily actions; they did mine over decades.”

“It is frustratingly difficult to cite a significant modern management concept that was not first articulated, if not invented, by Drucker,” says James O’Toole, the management author, and University of Southern California professor. “I say that with both awe and dismay.” In the course of his long career, Drucker consulted the most celebrated CEOs of his era, from Alfred P. Sloan Jr. of General Motors Corp. (GM) to Grove of Intel.

Deep into Drucker’s writings

Businessweek magazine in its special supplement after Drucker’s death highlighted his noteworthy achievements.

- It was Drucker who introduced the idea of decentralisation – in the 1940s – which became a bedrock principle for virtually every large organisation in the world.

- He was the first to assert, in the 1950s, that workers should be treated as assets, not as liabilities to be eliminated.

- He originated the view of the corporation as a human community, again, in the 1950s, built on trust and respect for the worker and not just a profit-making machine, a perspective that won Drucker an almost godlike reverence among the Japanese.

- He first made clear, still the ‘50s, that there is “no business without a customer,” a simple notion that ushered in a new marketing mind-set.

- He argued in the 1960s, long before others, for the importance of substance over style, for institutionalised practices over charismatic, cult leaders.

- And it was Drucker again who wrote about the contribution of knowledge workers – in the 1970s – long before anyone knew or understood how knowledge would trump raw material as the essential capital of the New Economy.

Drucker made observation of his life’s work, gleaning deceptively simple ideas that often elicited startling results. Shortly after Welch became CEO of General Electric in 1981, for example, he sat down with Drucker at the company’s New York headquarters. Drucker posed two questions that arguably changed the course of Welch’s tenure: “If you weren’t already in a business, would you enter it today?” he asked. “And if the answer is no, what are you going to do about it?”

Those questions led Welch to his first big transformative idea: that every business under the GE umbrella had to be either No. 1 or No. 2 in its class. If not, Welch decreed that the business would have to be fixed, sold, or closed. It was the core strategy that helped Welch remake GE into one of the most successful American corporations of the past 25 years.

Way forward

“We now accept the fact that learning is a lifelong process of keeping abreast of change; and the most pressing task is to teach people how to learn.” So said Drucker.

Discovering Drucker is one sure way of broadening awareness and understanding of management. This is true for practitioners and professionals alike. In Druckers own words, “follow effective action with quiet reflection; from the quiet reflection will come even more effective action.” Doing so will add value to most of our lives, enriching institutions, and nations alike.

(The writer, a Senior Professor in Management, and an Independent Non-executive Director, can be reached at [email protected], [email protected] or www.ajanthadharmasiri.info.)