Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Friday, 3 August 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

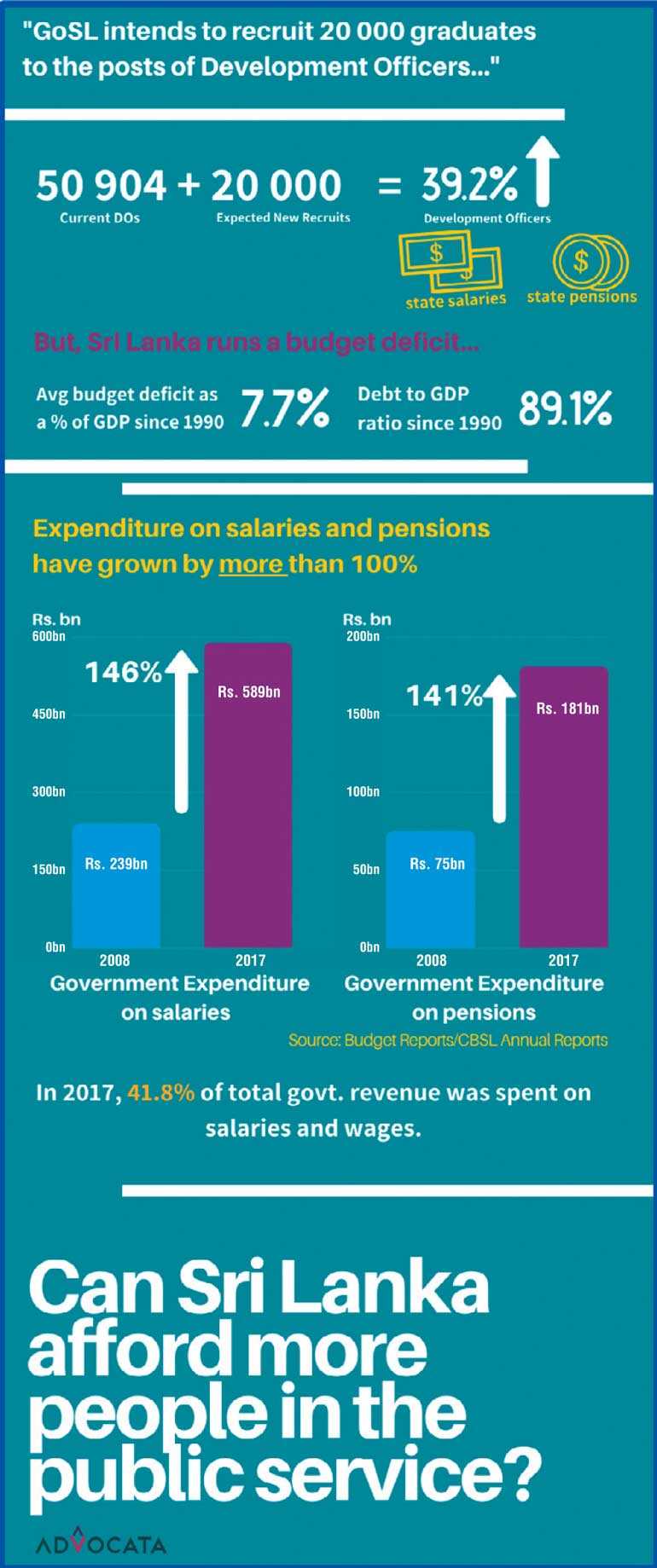

National Policies and Economic Affairs Additional Secretary Asanga Dayaratne announced recently that the Government will be appointing 20,000 graduates as Development Officers (DO) this month. This decision was taken after interviewing 57,000 graduates who had graduated on or before 31 December 2016 [1]. Additionally, the Cabinet will recruit 7500 more graduates after the elections in August, who will also be absorbed in as DOs later. [2]

National Policies and Economic Affairs Additional Secretary Asanga Dayaratne announced recently that the Government will be appointing 20,000 graduates as Development Officers (DO) this month. This decision was taken after interviewing 57,000 graduates who had graduated on or before 31 December 2016 [1]. Additionally, the Cabinet will recruit 7500 more graduates after the elections in August, who will also be absorbed in as DOs later. [2]

Why are these graduates being hired? It appears that this is a make-work program. As per recent press reports, it appears there are no real vacancies to hire people, but since these graduates are demanding jobs, jobs are being created by the State. The number of DO’s in Sri Lanka is 50,904 (2016 data). This new recruitment drive will increase the number by almost 40%. Such a sharp increase may mean other costs – they will need office space, furniture, computers and other facilities.

We may view this charitably, why not give the unemployed jobs? The question is, who pays for this?

Sri Lanka’s budget is already overstretched, the country has run a persistent budget deficit, averaging over 7.7% of GDP since 1990. The deficit has been met partly by borrowing, which is why the debt-to-GDP ratio has averaged 89.1% during the same period, almost double that of our peer group. The recent increases in taxes, VAT, income tax and others were needed to bridge the deficit. If more people are to be recruited, the salary bill will rise and there will be a need for increases in taxation. It will not be immediate, the tax increases will come a little later, but it will need to happen eventually, just as the recent tax increases followed increments given to the public sector in 2015.

What is happening here?

The Government is giving jobs to graduates, but then taxing people to pay for it. All that is happening is money is being transferred from the general public to newly-hired graduates. The graduates will be happy, but the public who sympathise with their plight may not realise that the salaries of these people will eventually be paid by them.

People forget that they pay tax every time they go to the market. VAT and import duties add a lot to the cost of a shopping basket or to a meal in a restaurant.

Are people getting richer? No. Will the graduates who get jobs be better off by having the public pay for this? What if the private sector creates jobs? Salaries would then be paid by businesses that hire people from the profits that they earn. The public will not be paying the salary bill. Instead, the businesses will from whatever they earn from their customers.

In fact, there are many unfilled vacancies in the private sector. While the public sector is overstaffing, there are 497,302 open vacancies in the private sector [4]. A local agricultural entrepreneur based in Polonnaruwa stated: “It is very difficult to find semi-skilled workers to operate our machinery because their attitude is such that they would rather stay home until they get a government job”.

The problem is that the jobs available do not meet the expectations of the graduates or that graduates lack the needed skills for these jobs currently open in the job market.

What the Government could do is assess the skills demanded by the job market, and invest in retraining these graduates. The retraining will be a one-off cost, but the graduates will have a productive job in places where they are actually needed, and there are no long term costs burdened on the public.

Some graduates do not like jobs in the private sector. An unemployed graduate from Ruhuna University stated: “I am a graduate from Ruhuna University. I’ve been unemployed for three years and I am waiting for a government job. I am not interested in a job from the private sector, so I have never applied for one. Government jobs are secure and unlike private jobs, they provide a pension.”

What they and the public must understand is that taxpayers cannot finance this anymore. There are many other problems that also burden taxpayers, including losses in State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs).

To create better jobs, the Government can facilitate new investment, especially in new sectors, by cutting red tape and improving the business environment. The sustainable way to better jobs is through new investment, not make-work programs.

Shyranthi Dhurairaj is an undergraduate reading for her L.L.B. at the University of London International Programs. She is also a part of the research team at The Advocata Institute. Advocata is an independent policy think tank based in Colombo, Sri Lanka. They conduct research, provide commentary and hold events to promote sound policy ideas compatible with a free society in Sri Lanka. Visit www.advocata.org for more information.