Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 22 June 2022 00:18 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

At this difficult juncture, to sail across a fierce storm, the only vessel we possess is our brains - Pic by Ruwan Walpola

“If you put bananas and money in front of monkeys, monkeys will choose bananas because monkeys do not know that money can buy a lot of bananas.” This was a part of a quote attributed to Jack Ma, co-founder of Alibaba Group. Monkeys are nothing more than an evolutionary prototype of humans. Thus if we assume the same bug continued its way to humans, they also may behave the same way.

Group. Monkeys are nothing more than an evolutionary prototype of humans. Thus if we assume the same bug continued its way to humans, they also may behave the same way.

Take Sri Lankans, for example. If we were offered, by a supreme God or any of the 330 million lessor gods we worship in this land, the choice of augmented brain capacity against a couple of billions of Dollars we would certainly select the latter. Just that we do not realise Dollars would solve our problems only for a few years, in the same way, monkeys will not be hungry for a few days with bananas. What we do not appreciate is the increased brainpower’s ability to earn more Dollars in the long term.

This piece presents two fundamental arguments. One – Sri Lanka’s current problems are created more by the sheer absence of brainpower – not just that of the leaders but the entire population. This may hurt our egos, but it is the reality. Two – most importantly, we can come out of it ultimately by increasing the brainpower of the entire population and not by taking more loans to cover existing ones. I have already touched on these ideas superficially in one of my previous articles (‘Sri Lanka needs a rapid economic transformation, not global sympathy’ FT, June 3, 2022) so this can also be treated as an extension where we can get into the nuts and bolts.

Understanding the problem: 5 Whys for Economists

We have discussed Sri Lanka’s current problems umpteen times on countless platforms varying from business journals to lunch groups and the parliament to petrol queues, but many still have not fathomed the gist of it. Mainstream economists identify it as gross mismanagement of the economy by successive governments that finally led to a situation we are so downgraded by rating agencies that we can no more borrow. (They feel comfortable as long as we were in a position to borrow, not repay, more.) Laymen, on the other hand, have formed their own theories. Politicians of different hues, they find, have pickpocketed public money to a level that made us bankrupt. Both these theories are partially correct but there is no strong evidence to fully support them. We certainly need a more plausible explanation.

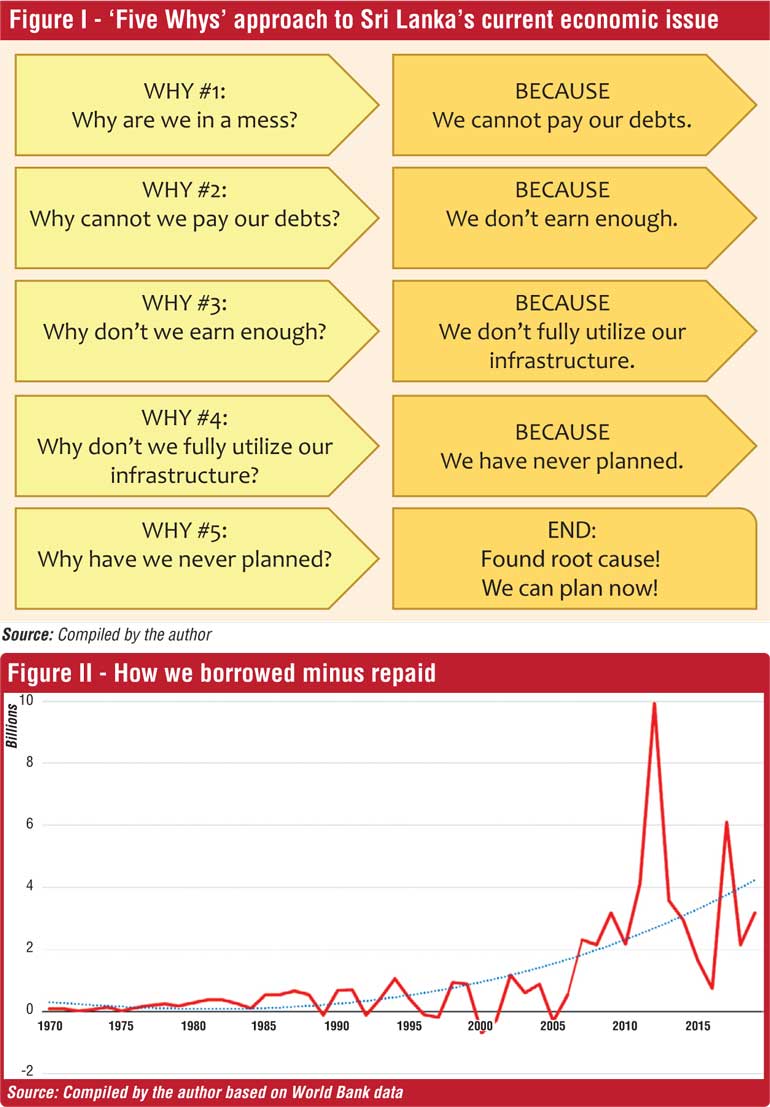

‘Five Whys’ (or 5 Whys) is an iterative interrogative technique used to explore the cause-and-effect relationships underlying a particular problem. Introduced by Sakichi Toyoda, the Japanese industrialist, inventor, and founder of Toyota Industries in the 1930s, it became popular in the 1970s. Toyota says they still use the approach to solve complex management issues. The method is remarkably simple: when a problem occurs, you drill down to its root cause by asking “Why?” five times. Then, when a counter-measure becomes apparent, you follow it through to prevent the issue from recurring. We too can use this approach to get into the root cause of the current issue. (Figure I)

Why is Sri Lanka, not Singapore, in trouble?

The answer to our ‘First Why’ is straightforward. Why are we in a mess? Because we cannot pay our debts? Yes. That was easy. We may have to think more to answer the Second Why: Why cannot we pay our debts? One can argue that we have taken debts exceeding limits. Sri Lanka’s debt burden is well over $ 50 billion and the Debt-to-GDP ratio was 105% by end of 2021. If you think this was high, wait until you learn the same figures for Singapore, which records $ 875 billion in debt with a Debt-to-GDP ratio of 152%.

If this surprises you please note Singapore has been borrowing heavily for the last two years to recover from its COVID-19-stricken economy. Cool. Nobody calls Singapore bankrupt. Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch, all rate Singapore AAA. They know Singapore’s books are in order and they will find no issues in repaying all their debts in time. I think you get what I am driving at. It is not because we have exceeded our limits. It is because we do not earn enough. That leads to our ‘Third Why’: Why cannot we earn more?

Multiple reasons. Not that I fully rule out mismanagement, corruption, and even wrong policy decisions. True, all these have cost us and decreased our earning capacity. Still leaving these perennial problems out there have been many other reasons. We often tend to ignore the twin impact of Easter bomb attacks and COVID-19 on the Sri Lankan economy for more than three years since April 2019. We have done great in tourism arrivals in 2018, the year before the former incident.

According to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka Annual Report for the year, a total of over 2.3 million visitors brought the island a total of nearly $ 4.4 billion – averaging $ 174 per tourist per day. Certainly not bad. 2019 first quarter saw the highest ever quarterly tourist arrivals ever. Annual arrivals saw an overall decline of 18% with 1.9 billion arrivals in 2019. The revenue dropped to $ 3.6 billion. Even there was a minor improvement in per tourist earnings. Still, the hit of COVID-19 was too stark. That took nearly an earning of $ 5 billion out annually.

Not that I argue that we would have not faced any economic issues if it were not for the Easter bomb attacks and COVID-19. We would have still faced the crisis, but the impact would have been low and it would have passed in a better manner.

What happened to all that money we borrowed?

Before getting further let me ask a pertinent question: Where did all the money we borrowed go? Yes, we lost part of it to mismanagement, corruption, and bad policies. Still, that’s not the whole story. To understand where it really went we have to have a more comprehensive look at the debts taken against the expenditures over the years. Figure II below helps by presenting the net borrowings (borrowings minus debt payments) of each year since the 1970s.

The pattern reveals a few interesting facts. Borrowings have been a bare minimum in the 1970s and only a minor increase is seen following the 1978 reforms. The jump in 1986 and the gradual increase thereafter can be directly attributed to the cost of conflict. Contrary to what is probably a laymen’s guess, the conflict was not the major reason for the heavy borrowings. Significant borrowings starts only in 2006 and experience a sharp rise post-conflict. For example in 2012 alone we borrowed nearly $ 10 billion. What for these monies were spent? We can find this by looking at the political agendas of the times. In one word, the answer is: Infrastructure.

Successive governments in the post-conflict times were heavily investing in building soft and hard infrastructure not just in urban areas but in rural areas as well. These were the times we built the second largest international airport, second-largest harbour, (rebuilt) destroyed rail lines for hundreds of kilometres (and a new line now extends up to Beliatta), all highways we have so far, and generously spent developing the North and Eastern provinces to the current level. From the soft infrastructure side, healthcare and education systems had a boost with a lot more new buildings, fresh staff, and facilities.

Apart from these, the governments have used the borrowings for major activities. One – to repay previous loans and two – to provide ardent citizen support in terms of the creation of more jobs in the public sector, and offerings hefty subsidies in many areas. The rationale behind each of these may or may not be justified. Still, we cannot deny the fact. These were where our money went into.

Infrastructure, infrastructure everywhere, not many a rupee that earns

Sri Lanka is not a poor country. Undoubtedly, not in terms of infrastructure. We have far better infrastructure facilities than some of the countries like Bangladesh, from which we now request financial assistance. The issue is we do not earn back from the infrastructure facilities we have built by making huge investments.

To be fair, there are other countries that continue to make the same mistake. Myanmar is one example. Naypyidaw is officially the capital of Myanmar. It has replaced Yangon as the administrative capital in 2005. Naypyidaw is well known for its unusual combination of large size and low population density. In reality, Naypyidaw is mostly a ghost city. Its 20-lane boulevards, like most roads in the city, are largely empty. Naypyidaw is the exact opposite of the twentieth-century busy and overcrowded metropolitan.

Hambantota is our own Naypyidaw. Look at what we have built over the last 13 years. The Hambantota Magampura International Port was opened in 2010 and is Sri Lanka’s second-largest seaport. Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport (MRIA) was opened in 2013 to be Sri Lanka’s second-largest international airport. Southern Expressway (E01) and Magampura Expressway (E06) already connect Mattala and Hambantota to Colombo and Katunayake BIA. The Railway network, now extended till Beliatta will reach Hambantota to be operational by 2023. There is an international cricket stadium at Sooriyawewa. Hambantota is also equipped with a modern hospital, hotels, and a conference hall of international standards. In short, no other place in Sri Lanka, except Colombo can boast this kind of infrastructure.

Hambantota: A twin commercial city?

If such facilities were available somewhere, in another country, it would have been by this time a successful twin commercial city. Still, Hambantota remains as rural as it was 25 years back. Why not use this infrastructure, which we have built with such colossal investments, for the benefit of the nation? This could be our ‘Fourth Why’: Why don’t we fully utilise our infrastructure?

To answer this crudely: Our issue was the limitations of our brain capacity. As a nation, we have never thought of such a solution. We never visualised Hambantota as developed as Colombo. Our brains were too small for that. For us, developing Hambantota was just a means of providing more ‘jobs for the boys’. We never had a plan that goes beyond that. Had we done something like Central Planning, as they did in Korea and many other countries, the long-term goals would have appeared there. We never did such planning after 1972-77. We thought market conditions would work bringing the jigsaw puzzle together and in no time Hambantota would be an economic centre. Sadly, that never happened.

Many Indian states are ‘twin-city’ ones, while Sri Lanka remained a single-city country for centuries after focusing only on the development of Colombo since the British times. Kandy or Galle are hardly considered ‘cities’ at the international level. Indian approach has been different.

Could Hambantota be another Mangalore or Coimbatore?

Mangalore, where I stayed for four years for my undergraduate studies, is one of the twin commercial cities of the Karnataka state. It was developed to the same level as the capital, Bangalore 352 km to the east. (Bangalore-Mangalore travel is an overnight affair like Colombo-Jaffna) Mangalore has its own airport – one of the two international airports in the state. Opened in 1951, by then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, it now serves as the destination mainly for flights from Middle Eastern nations. Unlike Mattala MRIA, it handles more than 1.25 million passengers a year recording a revenue of $ 8 million.

Mangalore seaport, which is just next to a fairly developed industrial area, is the seventh-largest in India, with annual revenue of $ 60 million. The city is famous for its chemical and oil industries. The latest additions are IT and outsourcing companies like Infosys, Cognizant, and Thomson Reuters with their offices at the heart of Mangalore, with multiple BPO centres. Export Promotion Investment Park (EPIP) is at nearby Ganjimutt while a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) has been constructed just next to Mangalore University.

Another IT park called Soorya Infratech is situated close to the city centre. From the images on Internet, I see the face of the city, which now has a population of over 600,000, has changed beyond recognition since I last left it over 25 years ago. Infrastructure-wise Hambantota can be compared to Mangalore; market-wise not.

Coimbatore, the second-largest city in Tamil Nadu after Chennai, is perhaps a better example, as it is closer to home. A major hub for manufacturing, education, and healthcare, Coimbatore is among the fastest-growing tier-II cities in the subcontinent. Housing over 25,000 small, medium and large industries with the primary industries being engineering and textiles. Coimbatore is called the “Manchester of South India” due to its extensive textile industry, fed by the surrounding cotton fields.

Lately, Coimbatore also gained fame for its software industry with a $ 100 million annual revenue. Coimbatore is a major centre for the manufacture of automotive components in India with car manufacturers Maruti Udyog and Tata Motors sourcing up to 30%, of their automotive components from the city. The auto industry employs 70,000 people and had an annual turnover of nearly $ 400 million. Please note all these happen just across the fence. Tamil Nadu is not one of the fastest developing states in India.

Where is Sri Lanka’s long-term central plan?

Hambantota may be just one chapter. Sri Lanka needs a more detailed long-term strategic Central Plan for the country. Like every plan, it should be SMART; Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound. This plan should be comprehensive and provide Dollar earning targets for each sector. (e.g. Apparel sector USD P billion per annum by 2025 and Q billion by 2030) There must be measurable and achievable KPIs for sectors and entities.

Achievements against these KPIs should be evaluated each year, with genuine interest to revise plans were there any obstacles. This process is familiar to us at organisational levels. Why do we shy off doing the same at the national level? In a way, this is exactly what the funding agencies and developed countries have been asking for some time: Were we ready to invest/assist what are their plans? (Read: Where will our money go? Do they end up in a mechanism that creates more Dollars and makes debt sustainable? Or, we put them in a bottomless pit?)

For reasons clear only to them, mainstream economists hate the Central Planning process. Their popular example is GOSPLAN – the agency responsible for central economic planning in the Soviet Union, which they call a “failure”. Perhaps we need to revisit international history a bit here. GOSPLAN wasn’t a failure, though at ground level there were attempts to artificially improve the production levels. If not for the increased production that happened with GOSPLAN, the Soviet Union would have probably lost WWII at Stalingrad, and perhaps I would be penning this article in German.

Even apart from that Central Planning is a methodology used by so many non-communist countries; most notably South Korea (7 Central Plans; the last one for the period 1992-96) and India (12 Central Plans the last one for the period 2012-17). In 2015 India replaced its Planning Commission with a Think Tank with a new name NITI Aayog (National Institution for Transforming India). It is debatable what level of planning we must get into, leaving the market to take from there, but Central Planning is not something we can afford to ignore in present circumstances.

Conclusion: We need planning; we need brains

At this difficult juncture, to sail across a fierce storm, the only vessel we possess is our brains. In foregone times, encountered difficult times villagers flocked around their elders, whom they thought the most experienced and the wisest, for advice. This is exactly what we should do right now. Sri Lanka must be led across the abyss by its most experienced and intelligent people, be they, politicians or officials. They should be independent, futuristic, realistic, and most importantly data-driven. This is not the moment for politics and ideologies. If we genuinely think, we lack that level of intelligentsia the next best move is to outsource. We hire foreign consultancy for many projects when local expertise is not available. Why make an exception in the most critical case?

(The writer is a policy researcher. He can be reached via [email protected]. Views expressed here are personal.)