Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Monday, 14 March 2022 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

This article is based on a presentation made on 26 February at the Monthly Seminar of the Sri Lankan Economic Association (SLEA), via the Zoom platform. Vaasa University, Finland and Karlstad University, Sweden former professor of Economics Professor J.A. Karunaratne made a presentation on “EU Agricultural Policy and Lessons for Sri Lanka”. The discussant was University of Peradeniya Department of Crop Science Professor Buddhi Marambe. The views expressed in the article are those of presenters and do not reflect views of SLEA.

EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and its implications for developing countries

EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and its implications for developing countries

During interwar period European economics faced severe scarcity of agricultural products. For instance, one loaf of bread in Germany was one million Deutsch Mark during the 1920s and 1930s. The great depression in Europe and elsewhere was also affecting this situation. This posed fundamental questions about laissez-faire economic policies which were being pursued in these countries. Government interventions in agriculture were minimal resulting in rising inflation, unemployment, food prices and creating anomalies in markets. Some argue that the disharmony created by these events was a contributory factor of the World War II.

After World War II, these countries realised that the internal enemy, i.e., scarcity of food, is more dangerous than the external enemy. Added to these factors was the fact farmers are influential in these countries due to their farm size being 30-300 hectares. Eventually, the need for direct government intervention was realised to promote agricultural produce and food supply and thereby guarantee food security.

Initial objectives of CAP were three-fold; support farmers and improve agricultural productivity, ensuring a stable supply of affordable food; safeguard European Union farmers ensuring a reasonable living; and keep the rural economy alive by promoting jobs in farming, agri-food industries and associated sectors.

|

| Vaasa University, Finland and Karlstad University, Sweden former professor of Economics Professor J.A. Karunaratne |

|

| University of Peradeniya Department of Crop Science Professor Buddhi Marambe

|

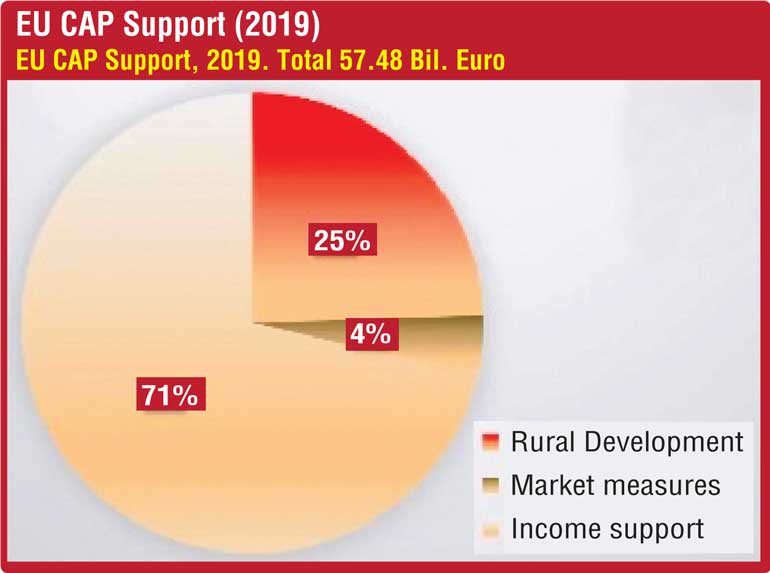

CAP consisted of three key components, i.e., (a) income support through direct payments to ensure income stability and remunerating farmers for environmentally friendly farming and delivering public services not normally paid for by the markets; (b) market measures to deal with difficult market situations such as a sudden drop in demand due to a health scare or a fall in prices as a result of a temporary oversupply on the market; and (c) rural development measures with national and regional programmes to address the specific needs and challenges facing rural areas.

As a result of these policies by 2019, 55% or about € 58 billion of the EU consolidated budget was allocated to agriculture and farming sectors. It should be noted unlike in Sri Lanka, a number of persons employed in the agriculture sector is about 4% of total employment and value addition to Gross Domestic Product is about 2% in the EU.

Due to rising oil prices and high wages etc., the EU decided to shift labour intensive, polluting intensive and oil-based industries to developing countries. EU was not willing to allow agricultural products from developing countries despite oil crises and related commodity crises and as a result, agriculture sector was never touched by the EU considering it as a holy cow. Decades of government support to agriculture in the EU has resulted in south countries in the EU producing agricultural goods and northern countries specialising in industrial goods making agriculture a balanced sector. This is manifestation of regional integration with different countries in a region specialising in economic activities and sharing among the region.

CAP and lessons for Sri Lanka

In view of the limited room available for Sri Lanka and other Asian countries to export agricultural and farm goods, excluding tea, rubber and a few other goods, to the EU countries. Even in the case of the market tea, rubber and coconut products have declined due to the emergence of new suppliers such as Kenya and Uganda for tea, the Philippines for coconut products and Indonesia and Brazil for natural rubber.

There are three lessons that countries like Sri Lanka should learn from the evolving agricultural policy in the EU.

Concentrate on the market for agriculture-related health products (natural products that do not contain various chemicals) for which the there is a growing market and Western industries are unable to cater. Evidence shows that the young in the West are most concerned about health products which have been produced without the use of animal products (i.e., animal fat) and in environmentally sustainable ways. Another example is the growing market in the UK for Coconut Water (imported from Thailand) as a substitute for Coca-Cola and similar fizzy drinks. Other foods that have export potential are Al0e Vera, Moringa and spices.

Diversify markets into fast emerging markets such as China and South Korea without relying only on Western markets. There is an absolute demand for some goods which can be developed and produced in Sri Lanka, in countries such as China.

Promote the intermarket of Sri Lanka without having to depend on imports of agricultural goods as Sri Lanka has been doing for the past many years. For instance, Sri Lanka (perhaps together with India) should be able to promote in the West the Ayurvedic Health Products (not medicinal products for which the procurement of permissions is hard to procure). These include cocking oil as well as ingredients used, for example, skin-care and hair-care products (i.e., coconut oil, natural fragrances).

In the current context, what matters is not globalisation but regional integration in which countries in a particular region specialise in producing different goods for exchange within the region, as is done in EU countries.

The presenter stressed the importance of the production and supply of essential items of food demanded by the populace of Sri Lanka. This is to assuage potential drive for demand-pulled inflation stemming from agriculture that can be harmful for the economy particularly at times of economic, social and strategic crises in the country. He maintained that the agricultural sector must not be treated as a residual of the mainstay instead a highly integrated sector of the economy. Such a policy would ensure that the population in rural districts is maintained as India and China have been able to do despite their rapid rush for industrial development as well as natural resources (i.e., water and land resources) are utilised. In this regard, public decision-making in the land has to play a central role.

The discussant opined that as in the EU agriculture sector has evolved all over the world and successive governments in Sri Lanka have taken many a measure to improve agriculture by considering food security as a top priority. Thanks to mechanisation, modernisation, and research and development measures, the agriculture sector in Sri Lanka, as in the EU, has improved significantly. For example, in about 1940, Sri Lanka with a population of about 6 million imported 60% of its rice requirements while in 2020 with a population of 21.8 million, more than our requirement in rice was produced.

He further highlighted that focus of agriculture policy should be to ensure food security where food is available at affordable prices at any time with required nutrition and safety. This cannot be achieved by adopting an organic fertilizer-only policy considering diversification in Sri Lanka in terms of 46 agro-ecological regions, seven soil types and about 200 soil series. It was also noted that government should take steps to implement the agriculture policy developed with EU assistance covering major eight Agri sectors.

The presenters emphasised the need for evidence-based policy formulation in the country as well as a priority should be given to food security when formulating agricultural policies.

The writer is the Sri Lanka Economic Association (SLEA) Vice President and Central Bank of Sri Lanka former Director.