Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday, 12 August 2023 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein

AE believed in a world that was governed by cause and effect. Everything in nature is determined by forces over which we have no control. Nature was everything from tiny dust particles to humans all the way to the sun, moon, and stars. For AE, there was an overarching cause and effect in the entire universe. How this operated was unreachable and mysterious to us and the sciences. The goal of science was to unravel these causes, like peeling off the layers of an onion, to ultimately lift the veil and reveal the mysterious mechanisms of how our world functions. Thus, to AE, nature was rational, causal, and capable of being comprehended by the human mind to various degrees of perfection

Ask anyone to name a scientist, and you will most likely hear the name, Albert Einstein (AE). He has attained an iconic status in history and is perhaps more responsible for his contributions to human knowledge than anyone else. Born in 1879 in Germany to Jewish parents, his scientific career witnessed turbulent times in Germany with the rise of the National Socialist Party of Adolf Hitler. In 1933, he decided to emigrate to the United States.

Ask anyone to name a scientist, and you will most likely hear the name, Albert Einstein (AE). He has attained an iconic status in history and is perhaps more responsible for his contributions to human knowledge than anyone else. Born in 1879 in Germany to Jewish parents, his scientific career witnessed turbulent times in Germany with the rise of the National Socialist Party of Adolf Hitler. In 1933, he decided to emigrate to the United States.

Einstein joined The Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, in the US. A quotation from AE, in German, is inscribed in stone above the fireplace in the faculty lounge of the mathematics building in Princeton: ‘Raffiniert ist der Herrgott aber boshaft ist er nicht’, which translated into English reads, ‘Subtle is the Lord, but malicious He is not’. This sums up AE’s vision of God. ‘Subtle is the Lord’ is also the title of his biography by Abraham Pais.

Was Einstein religious?

AE was raised as a Jew. From his writings, it is evident that AE was religious, but not in the sense that religion is understood by the average person. He was deeply influenced by the philosophy of Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677). He once said that ‘he believes in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the harmony of all that exists, not in a God who concerns Himself with the fate and the doings of mankind’. This, in contrast to atheism (no God), monotheism (one God), is termed pantheism. This is a belief where everything is identical to God; it means the universe, nature, and everything are ‘one’ with God. Others contend that pantheism is where the essence of the Divine is in everything, without everything being part of God.

There have been many great minds in history, from philosophers to religious leaders. Religions have also come in different forms: monotheistic (one god), polytheistic (many gods), and pantheistic. Obviously, the layman would like to know what this great mind of AE thought of religion. It is a good endorsement if this great mind is on your side of belief (be it a religion or atheism). Thus, one would like to know about AE: was he religious, did he go to church or a synagogue, what did he believe in, or was he an atheist?

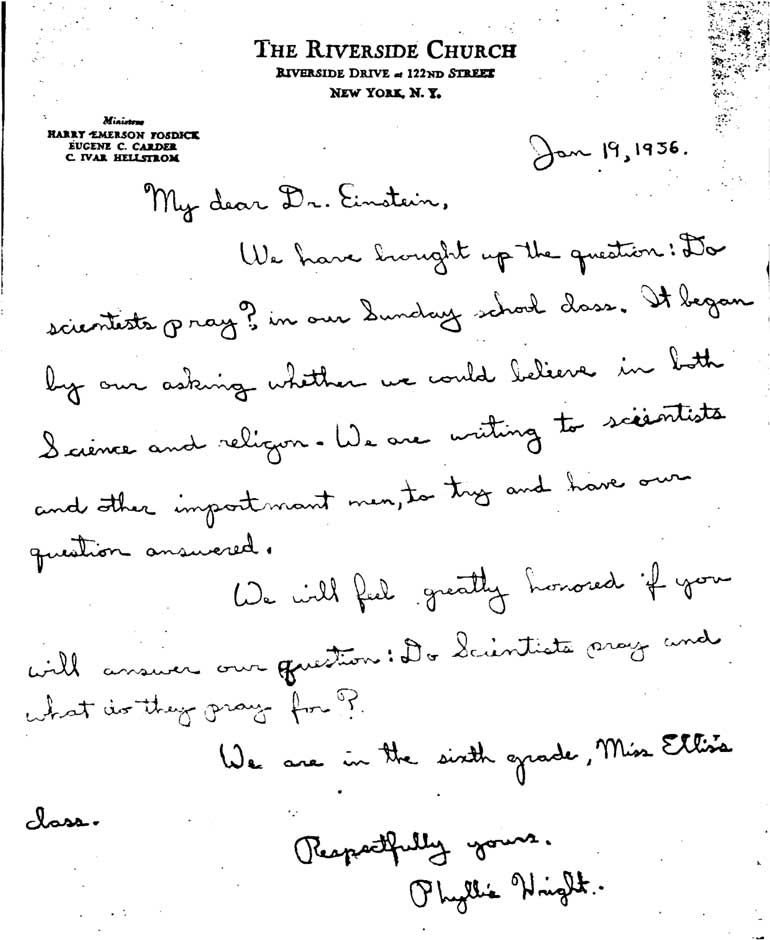

These questions were also of interest to a sixth-grade class of Sunday school children of the Riverside Church in New York. The question of what scientists believed interested these Sunday school children. So, Phyllis, one of the girls in the class, wrote the following letter, on behalf of her classmates and sent it off to AE, who by any measure was a good enough scientist.

My dear Dr. Einstein,

Jan 19, 1936.

We have brought up the question: Do scientists pray? In our Sunday school class. It began by our asking whether we could believe in both Science and religion. We are writing to scientists and other important men, to try and have our question answered.

We will feel greatly honored if you will answer our question: Do Scientists pray and what do they pray for?

We are in the sixth grade, Miss Ellis’s class.

Respectfully yours.

Phyllis Wright.

(transcribed from the original)

AE replied to Phyllis in a couple of days; his reply is given at the end of this article (if you are curious, please scroll down and come back here!).

AE corresponded with a lot of people during his lifetime. This included, scientists, heads of state, important people, authors, artists, and children. The children wished to send him birthday wishes, get his autograph, or receive advice from him for problems at school from their friends or with their parents. Some also gave him practical advice. In 1951, a six-year-old girl gave AE the following piece of advice:

“…I saw your picture in the paper. I think you ought to have a haircut, so you can look better.”

(From the Einstein website: https://einstein-website.de/en/correspondence-with-kids/)

AE’s view of science and the world

AE believed in a world that was governed by cause and effect. Everything in nature is determined by forces over which we have no control. Nature was everything from tiny dust particles to humans all the way to the sun, moon, and stars. For AE, there was an overarching cause and effect in the entire universe. How this operated was unreachable and mysterious to us and the sciences. The goal of science was to unravel these causes, like peeling off the layers of an onion, to ultimately lift the veil and reveal the mysterious mechanisms of how our world functions. Thus, to AE, nature was rational, causal, and capable of being comprehended by the human mind to various degrees of perfection.

One may look at this world from two aspects: the world of everything that is large – from the extinct dinosaurs, to planets, moons, suns, and galaxies – and the very tiny world of atoms and molecules, and the tiny particles that make up these atoms, out of which everything is made. The theories (of relativity), which AE put forward in 1905 and 1915, were perfectly capable of explaining the large world. However, the fundamentally tiny world of atoms and the even tinier particles within the atoms were governed by the forces of the atomic world. To explain the goings on in this tiny world, scientists (or rather physicists) at the time proposed the Quantum theory. This theory, by some of the greatest physicists who were cotemporaries of AE, included Max Plank, Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schroedinger, and many others. Central to this theory was the absence of causality and the necessity of a chance factor (probability) to explain the mechanisms of the atomic world. AE would have none of this; for him, causality was fundamental to the workings of this world, and he rejected this Quantum theory. For him, quantum physics could only be accepted, if there was another layer of causal explanation to explain this randomness. A world without causes did not make sense to AE, for it was something without harmony or divine beauty. It was this randomness and necessity of probability, which lies at the heart of Quantum Theory, that led him to make his famous statement that ‘God does not play dice’.

God does not play dice

In one of his many letters that he wrote to his friend and fellow physicist, Max Born, on 4 December 1926, he expressed his views on quantum mechanics. He wrote in German, of which there are many translations. As is the case with translating from the original, the informality and spirit of the message are usually ‘lost in translation’. The relevant sentence from the letter, in German, is: Jedenfalls bin ich überzeugt, dass der Alte nicht würfelt, which in English is: ‘In any case, I am convinced that the Old Man does not play dice’. The ‘Old Man’ is presumed to be God, and hence the phrase, God does not play dice.

Spinoza’s God

AE was much influenced by the philosophy of Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677). Spinoza was a 7th century Dutch philosopher. He ran into problems with the church by trying to move religion away from superstition and divine intervention, and in a direction that was far more impersonal. He was content that every projection of God as a person was the imagination of humans. However, he did not claim to be an atheist but was a strong defender of God. But this was not the God of the Old Testament. His God was not distinguishable from nature, and God was the universe; his God was impersonal and not interested in human affairs.

This view is called pantheism, which differs from traditional religions in two important ways: (i) God is not above and beyond the universe as in traditional conceptions of God; for the pantheist, He is the universe (He does not transcend the universe). (ii) The pantheist God does not have a will and cannot act in or upon the universe; He is a non-personal entity that pervades all existence. Thus, pantheism is a form of atheism since it denies an omnipotent God.

So, was Einstein religious?

Well, yes, but not in the sense that we look at religion. He believed in a deity that was, in a sense, nature itself. Perhaps no one knows what AE really thought. One can only derive his inner thoughts from his writings.

His biography describes his religious education. As a child, he was taught the elements of Judaism at home by a relative, and in school, he learnt the Catholic faith. When he was around 11 years of age, he went through an intense religious phase, following religious precepts in detail and composing several songs in honour of God, which he sang to himself on his way to school. All this came to an end when he was exposed to science. Religious matters were not discussed at home; his Jewish parents being liberal and non-dogmatic about religion. In fact, his father did not practice Jewish rites at home.

In an article for the NY Times in 1930, AE identified three stages of the evolution of religious thought in humans. In primitive man, it was Fear that evoked religious beliefs: fear of hunger, wild beasts, sickness, and death. Humans at this early stage of evolution had little understanding of causal relations, and the human mind resorted to creating illusory beings (gods, demons) who were responsible for the unfortunate happenings. To secure a favourable response and to appease the gods, sacrifices were offered to propitiate them. This led to the formation of a special priestly caste that acted as mediators between the people and the beings they feared. The second stage of religious development saw the desire for guidance, love, and support that lead towards a social or moral conception of God.

This was the God, to quote AE: “who protects, disposes, rewards, and punishes; the God who, according to the limits of the believer’s outlook, loves and cherishes the life of the tribe or of the human race, or even or life itself; the comforter in sorrow and unsatisfied longing; he who preserves the souls of the dead”.

AE ascribes to these two stages of religious development the anthropomorphic conception of God, where the human mind attributes human traits to non-human entities. He goes on to say that only exceptionally endowed individuals can rise above this level and identifies the third stage of religious development, which he calls cosmic religious feeling. According to him, there is no anthropomorphic conception of God corresponding to this stage, which is difficult to explain to anyone who is entirely without it. AE identified his religiousness with this stage of cosmic religious feeling. He identifies the beginnings of religion in many of the Psalms of David, and in some of the Prophets, and in Buddhism, which has a much stronger element of this cosmic religious feeling.

In 1940, he published an article in Nature on Science and Religion, where he wrote: But science can only be created by those who are thoroughly imbued with the aspirations towards truth and understanding. This source of feeling, however, springs from the sphere of religion. To this there also belongs the faith in the possibility that the regulations valid for the world of existence are rational, that is comprehensible to reason. I cannot conceive of a genuine man of science without that profound faith. The situation may be expressed by an image: science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.

It is evident from his writings that AE has given much thought to the nature of religion and its relationship to science. While mainstream religions can be communicated from person to person through religious books (Bible, Quran, Torah, etc.), how can Cosmic religious feelings be communicated in the absence of a definite notion of God or a theology? AE answers this by saying that “it is the most important function of Art and Science to awaken this feeling and keep it alive in those who are receptive to it”.

Thus, AE arrives at a conception of the relation of science to religion, where he states that for someone who is thoroughly convinced of the universal operation of the law of causation, one cannot entertain the idea of a being who interferes in the course of events. Such a person has no place for a religion of fear and equally little for a social or moral religion. A God who rewards and punishes is inconceivable to AE for the simple reason that a man’s actions are determined by necessity, external and internal, so that in God’s eyes he cannot be responsible any more than an inanimate object is responsible for the motions it undergoes. However, he argues that science has been unjustly charged with undermining morality in the absence of a religion.

He was a pacifist and believed that a man’s ethical behaviour should be based effectively on sympathy, education, and social ties and needs; no religious basis is necessary. Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hopes of reward after death.

For AE, cosmic religious feeling is the strongest and noblest motive for scientific research.

AE’s reply to Phyllis

While the letter from Phyllis was handwritten and in English, AE typed his reply to her in German.

January 24, 1936

Dear Phyllis,

I have tried to respond to your question as simply as I could. Here is my answer.

Scientific research is based on the idea that everything that takes place is determined by laws of nature, and therefore this holds for the actions of people. For this reason, a research scientist will hardly be inclined to believe that events could be influenced by a prayer, i.e., by a wish addressed to a supernatural being.

However, it must be admitted that our actual knowledge of these laws is only imperfect and fragmentary, so that, actually, the belief in the existence of basic all-embracing laws in Nature also rests on a sort of faith. All the same this faith has been largely justified so far by the success of scientific research.

But, on the other hand, every one who is seriously involved in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that a spirit is manifest in the laws of the Universe—a spirit vastly superior to that of man, and one in the face of which we with our modest powers must feel humble. In this way the pursuit of science leads to a religious feeling of a special sort, which is indeed quite different from the religiosity of someone more naïve.

I hope this answers your question.

Best wishes

Yours,

Albert Einstein

Finally, here is a quote from AE to summarise his views on religion:

“The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion that stands at the cradle of true art and true science. Whoever does not know it and can no longer wonder, no longer marvel, is as good as dead, and his eyes are dimmed. It was the experience of mystery – even if mixed with fear – that engendered religion. A knowledge of the existence of something we cannot penetrate, our perceptions of the profoundest reason and the most radiant beauty, which only in their most primitive forms are accessible to our minds: it is this knowledge and this emotion that constitute true religiosity. In this sense, and in this alone, I am a deeply religious man.” From his essay The World As I See It (1930)

It appears that atheists, monotheists, Jews, or polytheists cannot claim AE to be on their side. Only pantheists, in a very broad sense, could claim him!

I am grateful to the Albert Einstein Archives of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, for sharing a copy of the original letter from Phyllis.

(The writer is a retired scientist, who is keen on popularising science to the public. He can be reached at [email protected].)