Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday, 22 November 2024 00:53 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Thusiyan Nandakumar

The 2024 Sri Lankan Parliamentary election concluded last week, in which the ruling National People’s Power (NPP) gained a record majority and made headway into the Tamil homeland. There were notable casualties for senior Tamil nationalist politicians and for the first time ever a southern political party managed to gain a majority in all but one district in the north-east. Commentators have since speculated whether the result spells the beginning of the end for Tamil nationalist politics.

But voter data from last week paints a different picture.

Instead, the figures highlight a range of factors, including the fall of other southern Opposition political parties, leftist coalitions and paramilitary groups that allowed the NPP to siphon votes and grow their base amongst those who had already previously voted for pro-state forces.

And it also reveals that rising Tamil independent voices eroded at the older Tamil parties and brought a range of new nationalist voices to the fore in the north, but the more established parties still managed to grow their voter base in the east.

From 2020 to 2024

For the purposes of this piece, I will be comparing voting patterns from 2024 to the previous Parliamentary polls held in 2020.

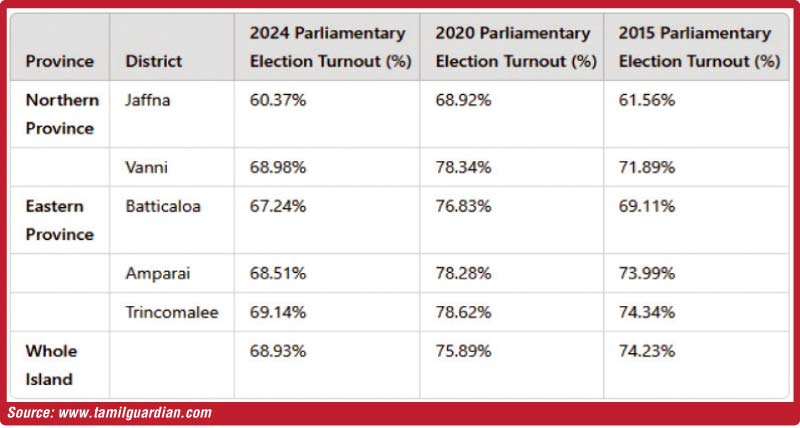

To begin, it is important to note voter turnout for the 2024 Parliamentary polls was historically low. As the Tamil Guardian reported last week, in comparison to the previous two parliamentary polls, turnout was lower in every district in the north-east. Figures dropped even from the Presidential polls held just two months ago.

This election also saw an influx of independent candidates and newly formed political parties compete. In places like Jaffna, where there were over 36,000 fewer votes cast in 2024 compared to 2020, this meant that there were hundreds more candidates competing for even fewer votes.

Jaffna is a good place to begin examining the Tamil vote.

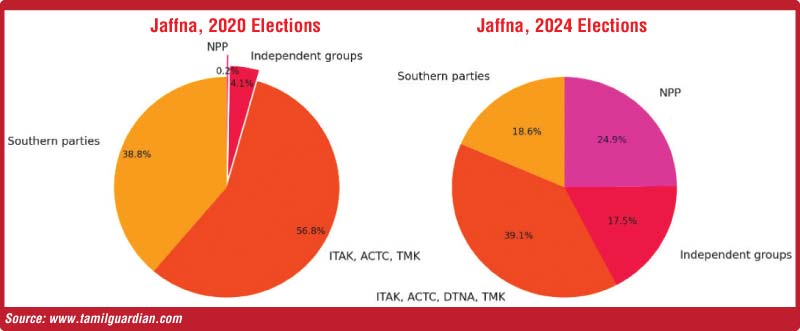

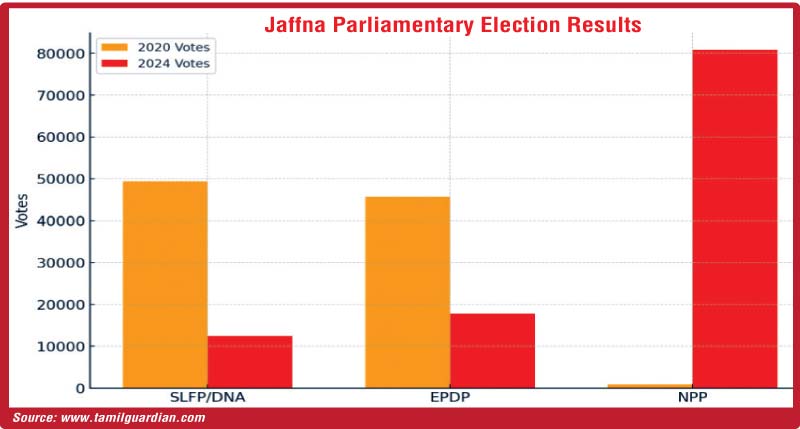

As the cultural capital of Eelam Tamils, the growth of the NPP vote in the district captured Colombo headlines. In 2020, the NPP had just 853 votes. In 2024, it recorded 80,830 votes.

Where did those 79,777 votes come from?

Southern parties falter in Jaffna

Many have pointed to the demise of the older Tamil politicians and parties, which for years have been plagued by factional disagreements. The Tamil National Alliance (TNA), a coalition which was headed by the Ilankai Tamil Arasu Katchi (ITAK), had been disbanded and the party itself facing internal turmoil. The former constituents, mostly Tamil militant groups turned political parties, came together to compete under the Democratic Tamil National Alliance (DTNA) banner. The Tamil National People’s Front (TNPF), which competed under the symbol of the All Ceylon Tamil Congress (ACTC), remained staunchly independent from other Tamil parties, whilst the Tamil Makkal Kootani (TMK) (also known as the Thamizh Makkal Tesiya Kootani or TMTK) saw veteran politician C.V. Wigneswaran retire and a handful of new faces come to the fore.

Whilst these parties have key disagreements, including sometimes internally, they all broadly espouse the more mainstream Tamil nationalist politics – particularly when it comes to topics such as genocide recognition, Tamil nationhood and international accountability. Though the differences can be sharp, for example when it comes to implementation of the 13th Amendment, they can be considered a loose bloc of established Tamil nationalist voices.

In 2020, the ITAK, ACTC and TMK together received 204,197 votes.

Four years later, the ITAK, ACTC, DTNA, and TMK together received 127,121 votes.

In total, they lost 77,076 votes.

Yet it would be simplistic – and wrong – to say that all these lost votes went straight to the NPP, without examining what happened to other parties in the district.

Southern-based parties have long held a presence in the north-east. Some are a legacy of a time when the Sri Lankan State would ferment paramilitary partners in its war against the Tamil people. Others are a mix of left-wing union linked organisations or established Sinhala political parties that have sought to expand their presence into the Tamil homeland. For years, they have held a significant proportion of the votes in Jaffna.

Sri Lankan Government or Government aligned Tamil parties (such as the United National Party (UNP), Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLF) or Eelam People’s Democratic Party (EPDP)), overtly racist Sinhala extremist parties (such as the Our Power of People Party (OPPP)), island-wide leftist parties (such as the Frontline Socialist Party (FSP)) and one EPDP-breakaway group that ran independently received 139,180 votes in 2020.

But four years later that same formation received just 60,468 votes.

That is a loss of 78,712 votes – a number even greater than the Tamil parties lost.

The loss seems even more significant when examining just two parties that were the staunchest supporters of the Sri Lankan State – the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) that was formerly of Mahinda Rajapaksa and the paramilitary Eelam People’s Democratic Party (EPDP). Together they polled 95,170 votes just four years ago. That is a number higher than what the NPP achieved last week.

In 2024 however, the EPDP and Democratic National Alliance (DNA) that the former SLFP Jaffna lead Angajan Ramanathan was standing for, managed to garner just 30,157 votes – a loss of over 65,000 votes.

The NPP’s gain could have come from that range of parties, just as much as it could have come from the older Tamil parties. Given the sweep that the NPP managed to make across the rest of the island, it is a plausible argument.

A shattered Opposition has meant that in all districts outside of the north-east, the NPP secured an outright majority whilst other southern parties were left decimated. Parties that boasted the once mighty names of Mahinda Rajapaksa and Ranil Wickremesinghe have been left with three and five seats respectively, whilst Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s NPP has 159.

Many Sinhala voters saw little else on offer from the other southern parties and decided to cast their vote for the NPP. This pattern more than likely carried over into the north-east strongholds that some southern parties have long held. Further examples below will demonstrate how that is even clearer, and more crucial, for the NPP voter base.

The rise of the independent

What then of the Tamil vote? At this juncture, it is worth examining the growth of independent candidates.

In 2020, independent candidates (excluding the one breakaway candidate from the EPDP, who would later join the SJB) polled 14,900 votes.

This year, despite hundreds standing presenting stiff competition, independent candidates polled 56,893 votes.

There were 21 independent groups in total that polled over 100 votes each, including overt Tamil nationalists such as Dr. Ramanathan, former TNA MP Saravanapavan, and former LTTE cadres. Independent 16, for example, saw the president of a northern fisheries association stand for election. Independent 2 is a young Tamil lawyer who spoke in interviews of how the older Tamil parties stifled youth participation. Independent 13 paid tribute to Pon Sivakumaran, the first Tamil militant to die in the independence struggle, after handing in their nomination papers.

The 41,993 votes the independent candidates gained were more likely at the expense of the more established Tamil nationalist parties, with the polity voting for fresh Tamil voices amidst the ongoing turbulence between the older figures. It is a pattern that occurs throughout the north-east as independent votes rose in each of the five districts.

That transfer to independents and the lower turnout on its own could account for the loss of the older Tamil nationalist party votes. They did not all necessarily pass over to the NPP.

A collapse for the SLPP

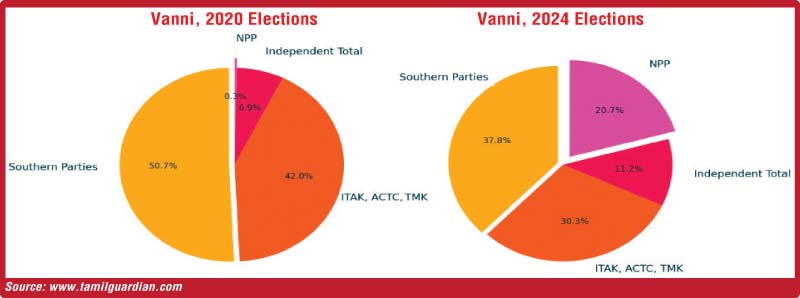

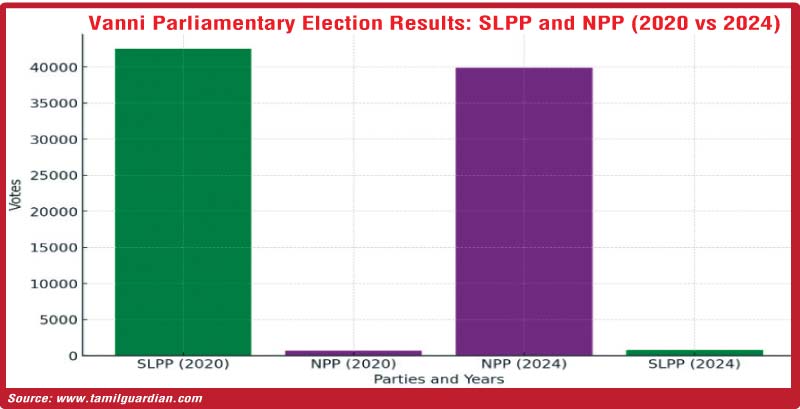

A similar pattern is seen in the Vanni, where amidst lower voter turnout, the older Tamil parties did lose votes. However, so too did the southern parties, whilst the growing number of independents and the NPP gained.

In the Vanni, the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) polled similar numbers from 2020 to 2024 at over 30,000 votes. But the Rajapaksa-led Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) vote collapsed entirely. The Rajapaksa led coalition went from 42,524 votes to just 805 votes.

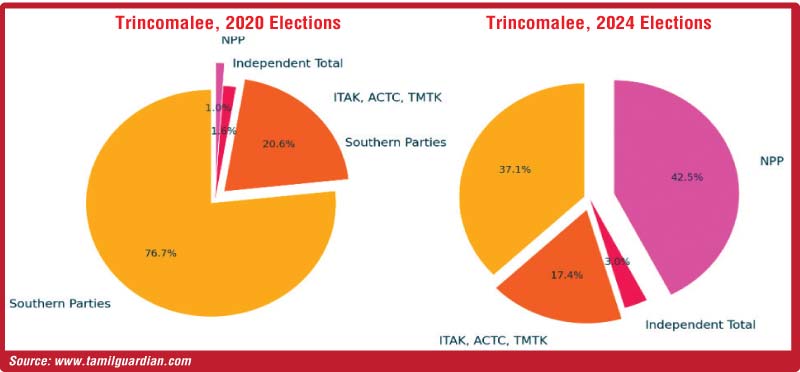

The same happened in Trincomalee, where the SLPP went from 68,681 to 1,399. Who did these votes go to instead? For Tamils in the district, where the TMK did not field a candidate, the ITAK and ACTC managed to garner a combined total of 35,710 votes – just 8,230 shy of the total they achieved with the TMK in 2020.

The NPP however gained a massive 84,805 votes, the vast majority of which would have undoubtedly come from supporters of other Southern parties, who lost more than 87,000 votes.

Tamil nationalism on the rise?

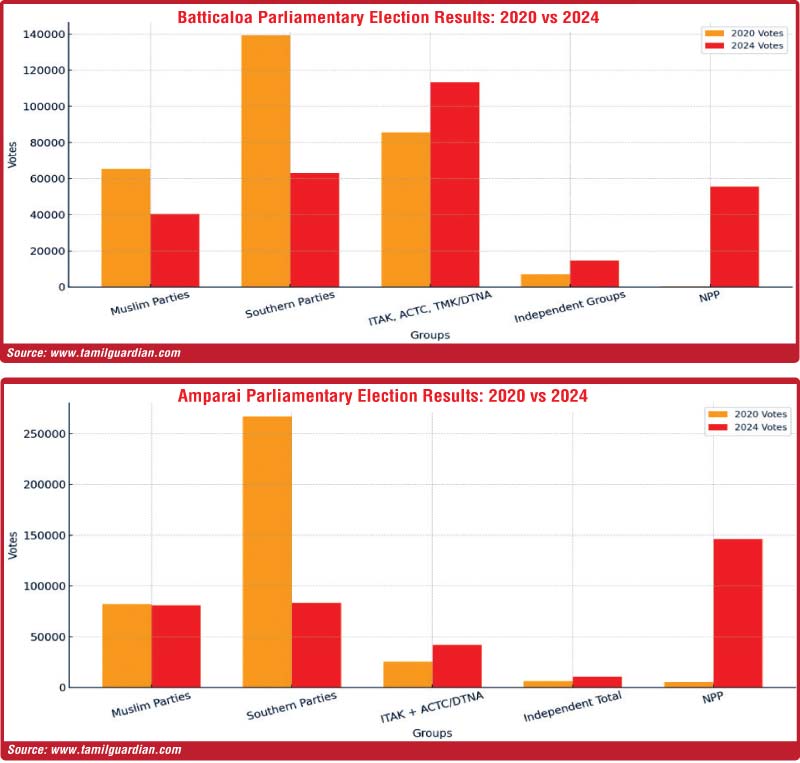

Travelling to the east further reinforces the point that Tamil nationalist politics is not yet dead. Indeed, if one assumes it is defeated in Jaffna, then looking at Batticaloa and Amparai it seems to be on the rise.

Batticaloa is the one district on the island that the NPP did not secure a majority in and a region that saw a growth in voters that chose the more established Tamil nationalist party.

The ITAK alone managed to grow its votes from 79,460 to 96,975, despite the breakaway DTNA also securing 14,540 votes for itself. A similar phenomenon occurs in Amparai, where ITAK went from 25,255 in 2020 to 33,632 in 2024, with the DTNA also gaining 7,227 votes. This growth comes with independent votes too also on the rise.

In these regions again, the more established southern parties saw dramatic falls once more (from 126,012 for the SLPP in 2020 in Amparai, to just 6,654 in 2024).

The NPP meanwhile, steadily grew, easily absorbing those lost votes.

Going beyond the headlines

In any electoral contest, the numbers on their own never tell the full story. But closer scrutiny of the data and the voting patterns that have merged, fit the broader image that is emerging from the Tamil homeland.

Southern-based parties fared badly across the north-east, reflecting what occurred throughout the rest of the island. And in regions such as the Vanni, Batticaloa and Amparai, the collapse of parties such as the SLPP would have meant ripe pickings for the NPP. Examining the data, it seems that it was the electoral fall of these paramilitary organisations and southern parties, which was markedly more significant than for the older Tamil parties, that played a greater role in the growth of the NPP.

Despite the growth of NPP votes, however, there has been a definitive lower turnout in the north-east, hinting at growing dissatisfaction with electoral politics. And the more established Tamil political parties did see a fall in votes in the north, with some senior figures losing their seats. But it is certainly not a whitewash, and Tamil nationalist parties still hold significant sway. Meanwhile independent voices, many of which are fiercely Tamil nationalist, wielded significantly more influence. In Jaffna, despite the much stiffer competition for votes with a lower turnout, fewer overall voters and one less seat, one independent candidate even got elected.

For the island, this means two more salient things. Firstly, the lack of any concrete southern opposition across the island handed the NPP a majority which now allows it to amend the constitution and rule virtually unhindered.

Secondly, Tamil nationalist politics is very much a hugely influential factor in the Tamil homeland. Almost all of the candidates in the north-east espoused Tamil nationalist rhetoric – including those of the NPP. At one rally in Jaffna for example, Dissanayake was compared favourably to LTTE leader Prabhakaran. Candidates paid tribute at LTTE cemeteries and at Mullivaikkal, the site of the Tamil genocide. This widespread normalisation of Tamil nationalism is even more evident when looking beyond the ballot. The paying tribute to LTTE leaders such as Thileepan has become a routine feature in the Tamil calendar, and across the north-east Tamils are currently preparing to commemorate Maaveerar Naal – a day for fallen LTTE fighters.

The recent polls have provided a small insight into the politics of the north-east, but elections themselves are not always accurate barometers of political sentiment. To get a more accurate picture, we need to go beyond the headlines.

(The writer is the Editor, Tamil Guardian.)