Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday, 14 January 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Overview

The policy debate towards negotiations on Free Trade Agreements (FTA) has been intensified after Sri Lanka signed a Free Trade Agreement with Singapore in 2018. Almost two decades ago, Sri Lanka entered into its first-ever FTA with India, followed by a similar trade pact with Pakistan.

After a period of long silence, negotiations are currently underway with an open-ended list for negotiation of more FTAs, the rationality of which has come under heavy criticism without the backing of empirical evidence-based research work. The gravity of such criticism has even led to the appointment of a Presidential Committee to evaluate the Sri Lanka-Singapore FTA (SLFTA) and make recommendations.

Free Trade Agreements typically seek to reduce trade barriers between partner countries. The new trend is that many of the liberalisation commitments of these trade agreements go beyond the trade in goods to include broader scope on provisions on services, intellectual property, trade facilitation, customs cooperation, Government procurement, ecommerce and investments as well.

FTAs have been seen by many as promoting broader economic integration. Globally, these wide-ranging and controversial bilateral and regional trade arrangements have thus emerged as part of the trade policy landscape.

In the backdrop of these recent developments, the main objective of this article by the Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry of Sri Lanka (FCCISL) is to shed some light on the strategic approach, preparatory process and matters of concerns of other countries when entering into FTAs and finally to provide a set of recommendations for the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) to develop a more pragmatic approach towards FTAs so that the Sri Lankan business community would hopefully achieve tangible economic advantages and commercial benefits across the wide spectrum of industries and services.

Definition of FTA: In simple terms, an FTA is an agreement between two or more countries to establish a free trade area where commerce in goods and services can be conducted across their common borders, without tariffs or hindrances.

(1) Types of trade agreements

Broadly, there are three types of trade agreements.

(a) Unilateral trade agreement. It occurs when a country dismantles trade restrictions with partner countries without any reciprocity from other partner country. It would put the country, which is receiving tax reliefs at a competitive advantage. E.g. GSP+ by EU to Sri Lanka. The United States and other developed countries only do this as a type of foreign aid. They want to help emerging markets strengthen certain industries. It helps the emerging market’s economy grow.

(b) Bilateral trade agreements: This is happening between two countries. Both countries agree to loosen trade restrictions to expand business opportunities between them. They lower tariffs and confer preferred trade status with each other. The sticking point usually centres round key protected or subsidised domestic industries. For most countries, these are in the automotive, oil or food production industries.as of today United States has 16 bilateral agreements.

(c) Multilateral Trade Agreements: These are among three countries or more and are the most difficult to negotiate. WTO agreements are typically multilateral agreement involving its member countries. The greater the number of participants, the more difficult the negotiations are. They are also more complex since each country has its own needs and requests and once negotiated, multilateral agreements are more powerful than bilateral trade agreements. They cover a larger geographic area. That confers a greater competitive advantage on the signatories. All countries also give each other most favoured nation status. They agree to treat each other equally. For example, the Asia Pacific Trade Agreement in which Sri Lanka is also a signatory. The largest multilateral agreement is the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). It is between the United States, Canada and Mexico which is however to be replaced by an agreement called United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA).

Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs) and FTAs coexist and consistent with the rules of WTO/GATT multilateral trading system as provided in Article 24 and Article 5 of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), though such agreements constitute a departure from the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) rule which is the fundamental principle of non-discrimination of the WTO agreements. Under this MFN commitment countries are not allowed to discriminate between their trading partners simply implying that If country grants a special favour (such as a lower Customs duty rate for one of their products) to a country, then it has to be extended for all other WTO members.

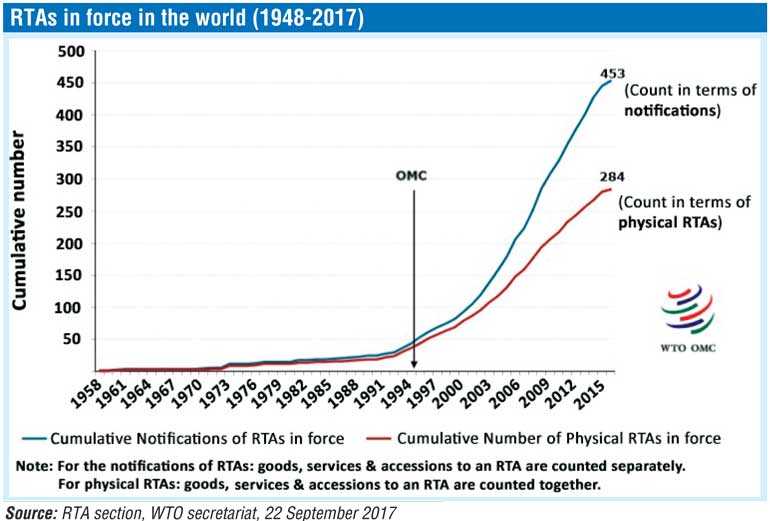

RTAs and FTAs have become a key trade policy instrument for most countries, and thus a major feature of today’s trade landscape. The number of bilateral FTAs negotiated between developed countries and developing countries has increased dramatically during the recent years. All WTO members are involved in at least one RTA, and bit more than half have at least five RTAs. It is reported that as of October 2017 globally there are about 284 “physical” RTAs in force of which majority are from Asia pacific region (AP).

(2) Reasons for the surge in RTAs /FTAs in the world

A complex mix of external and internal factors, as well as economic, political and security-related factors is behind the expansion, intensification and diversification of RTAs/FTAs.

External factors: Securing markets and providing export opportunities for domestic companies by dismantling the trade barriers between participating nations. The expansion of production that results from increased export opportunities enables companies to reap the benefits of economies of scale, which in turn leads to produce more competitive (price wise) products. Access to markets and the expansion of export opportunities are particularly important for companies from smaller country. For example, it was very important for companies in Canada and Mexico to gain access to the US market and Sri Lankan companies to enter in to India, China and EU. The importance of securing markets as a motive for participating in RTAs has become even greater as regionalism has expanded day by day.

Internal factors: Economic growth from increased efficiency due to greater competition as a result of the markets being opened. Since the 1970s, policymakers have come to recognise the benefits of liberalisation of foreign trade and investment, deregulation and the removal of domestic regulations have facilitated high economic growth in the developing countries of East Asia, as well as industrial nations such as the US and the UK.

Role of World Trade Organization (WTO): WTO provides a forum for negotiating amendments aimed at reducing obstacles to international trade and ensuring a level playing field for all, thus contributing to economic growth and development. The WTO also provides a legal and institutional framework for the implementation and monitoring of these agreements, as well as for settling disputes arising from their interpretation and application. WTO, which was established in 1995, and its predecessor organisation the GATT have helped to create a strong and prosperous international trading system, thereby contributing to unprecedented global economic growth.

(3) Sri Lanka’s case – Learning from other countries

The way countries viewed these trade blocks such as RTAs and FTAs have changed over time. For some reasons, if the current policy makers of GOSL believe FTAs would bring meaningful benefits to the country by way of promoting trade and accelerate economic growth, it is of paramount importance that our negotiators to learn from good practices adopted in other countries in negotiating free trade agreements. Following a very brief survey the following section below attempts to highlight some perspectives as to the inclusive consultation and analytical process, safeguarding defensive interest or even back off from negotiation if desired goals of FTAs are not likely to yield meaningful benefit for the country. We have selected countries - two from our own region and a few developed countries where there are systematic approaches and domestic trade interest driven approaches are adopted by well-experienced negotiating teams for pursuing bilateral FTAs.

(a) Australian approach to free trade

Australia has adopted cautious approach in selecting countries for entering into FTA. The Australian Government’s approach has been to negotiate comprehensive agreements that seek substantial reductions in trade barriers and included provisions on matters such as intellectual property, competition policy and trade facilitation.

In line with global trends, Australia has been pursuing bilateral and regional agreements enhancing Australia is broader economic, foreign and security policy interests. Australia has entered into 10 FTAs with both individual countries and groups of countries. A number of other agreements are currently under negotiation.

In 2009 the Australian Government requested the productivity commission to provide advice on the effectiveness of trade agreements in responding to national and global economic and trade developments and in contributing to efforts to boost Australia’s engagement in the region and evolving regional economic architecture. (The Productivity Commission having consulted all key stakeholders and having conducted studies in the academic literature, and research and quantitative analysis submitted a detailed report to the Government.)

(b) Some important key findings of the report

(The term Regional/Preferential Trade Agreements (RPTAs) in fact refers to Free Trade Agreements throughout the report)

(1) Theoretical and quantitative analysis suggests that tariff preferences in BRTAs, if fully utilised, can significantly increase trade flows between partner countries, although some of this increase is typically offset by trade diversion from other countries.

(2) The increase in national income from preferential agreements is likely to be modest.

(3) The Commission has received little evidence from business to indicate that bilateral agreements to date have provided substantial commercial benefits. This may be because the main factors that influence decisions to do business in other countries lie outside the scope of BRTAs.

(4) While BRTAs can reduce trade barriers and help meet other objectives, their potential impact is limited and other options often may be more cost-effective.

(5) Current processes for assessing and prioritising BRTAs lack transparency and tend to oversell the likely benefits.

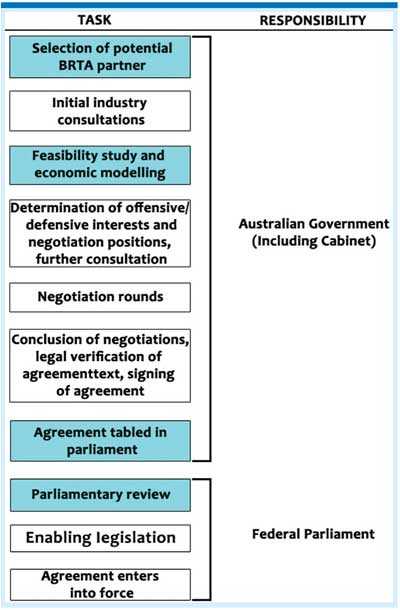

(c) Existing model of Australia towards FTA negotiations

See table 2. (The key learning points from the Australian model is selection of potential RTA/FTA partner, feasibility studies, economic modelling and parliamentary review by the Federal Parliament.)

(4) Politics of Free Trade Agreements

Suppose that an opportunity arises for two countries to negotiate a Free Trade Agreement (FTA). Will an FTA between these countries be politically and economically viable? And if so, what form will it take? These questions take us into the realm of international relations and the hard realities of international economic diplomacy and bargaining parity and power.

Governments all over the world have been meeting frequently of late to discuss the possibility of their forming bilateral or regional trading arrangements. These trade negotiations have never been easy, nor have they always been successful. Such activity towards bilateral and regional FTAs reflect in part the failure of the Multilateral Trading System and to make any progress in market access and trade negotiations where the intransigence and protective interests of the developed and powerful countries reign supreme.

It’s noteworthy to quote that studies of the UNCTAD evaluating the failure of many developing countries to obtain substantial benefit from Free Trade Agreements, attribute such failures to the predominance of vested business interests/groups which influence political authorities to enter into agreements and concede high levels of liberalisation adversely affecting the majority of industry/agriculture/in return for the concessions received by these few vested interest groups. In the case of Sri Lanka, it is a well-known fact that during the FTA negotiations with Singapore, Sri Lankan large-scale exporters and conglomerates especially in the apparel sector encouraged the Government of Sri Lanka to sign the agreement due to likely economic benefits for them.

FCCISL has no reason to doubt the efforts of GOSL in its efforts to maximise aggregate national welfare and economy wide benefits for enhancing the living standard of the people through creation of trade using FTAs. However this great intention is not enough. The Sri Lankan Government should also understand the nature of the game between governments as well.

(a) Lessons from Pakistan-China FTA (the bad politics of a good idea)

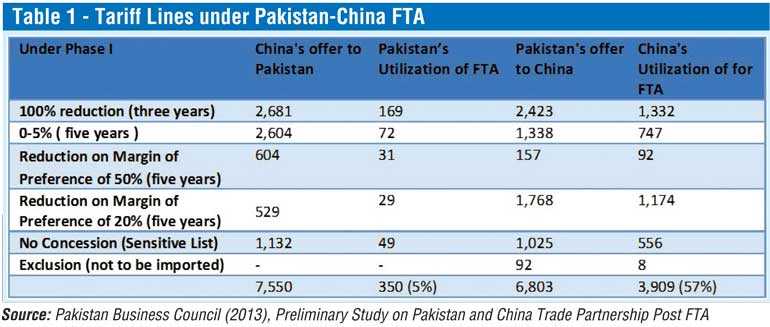

Pakistan and China signed up a FTA in 2006 and made it effective 2007. Under Phase (1) of the agreement China agreed to eliminate/reduce tariffs on 6,418 product lines, and Pakistan was to eliminate on 6,711 product lines over a period of five years.

As of end of 2013, bilateral trade reached little over $ 9 billion, as compared to $ 3.5 billion in 2006 prior to the FTA being implemented while the trade imbalance has grown in favour of China during this time. It’s noteworthy to mention that during the phase (1) China made substantial use of the FTA and has managed to utilise 57% of the concessions under the FTA, compared to mere 5% in the case of Pakistan. (Please see below.)

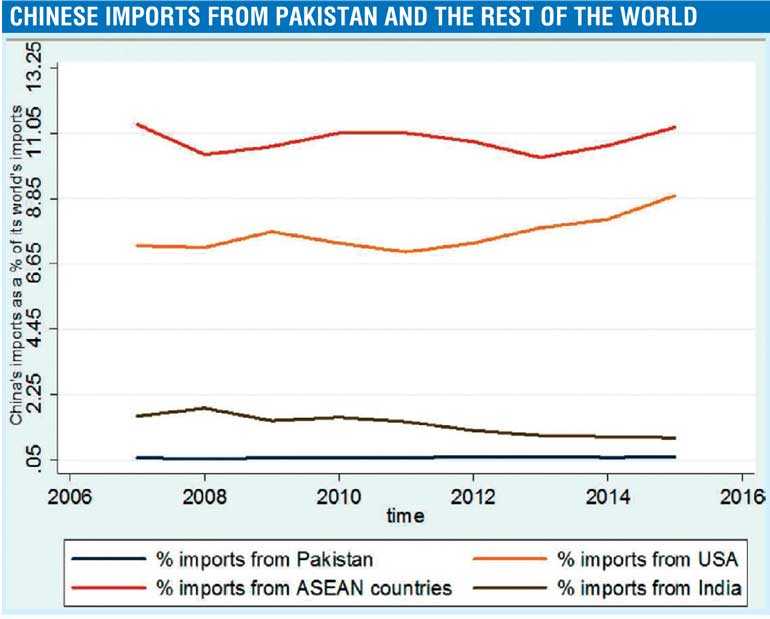

Under the FTA has China effectively increased buying from Pakistan? What is Pakistan’s position as an exporter to China compared to other countries which export goods to China after signing similar FTAs? Chart 3 tells the story!

As evident from the graphical presentation on bilateral trade between the two countries over the last decade, Pakistan has failed to derive the benefits out of the FTA with China. In March 2017 Lahore School of Economics and Pakistan Business Council have attributed the following factors for poor performance of Pakistan.

a. In the same year, (2007) China entered into an FTA with ASEAN and awarded higher or equal tariff reductions to competing ASEAN countries for products for which Pakistan possesses big export potential in the Chinese market. As a result, tariff preferences enjoyed by Pakistan under the FTA have been eroded and similar products of ASEAN countries became more attractive to Chinese importers.

b. During the negotiations Pakistan’s top exports to the world (and China) have been placed in China’s negative list despite the demand for such goods being high in China.

FTA concessions offered by Pakistan seem to be more beneficial for China both in terms of the number of product lines utilised and variety of type of product lines utilised. In this context, the theory of give and take has not applied equally to both countries.

At the time of signing the FTA between two countries, during Phase (2) it was agreed to remove 90% of tariff lines. However, no negotiation was begun even three years after the lapse of the phase due to the refusal by the Pakistan to commence the negotiations due to the negative impact created by phase (1) on the Pakistan economy.

(The writer is Secretary General/CEO of FCCISL. He was a member of the NTFC study tour to Australia in 2018 organised by ITC/EU.)

(To be continued.)