Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday, 23 December 2024 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

|

As a transhipment port, the Port of Colombo ranks among the best in the world, primarily due to its excellent linear connectivity and capital-intensive seaside operations. However, as landside operations are riddled with extended cargo clearance times, excessive compliance requirements and lengthy waiting times for container pick-up and delivery, its performance stands below par against gateway ports. This not only significantly impacts the quality of service experienced by the thousands of customers who visit the port each day, but may also deter potential foreign investors looking to set up businesses in Sri Lanka.

As a transhipment port, the Port of Colombo ranks among the best in the world, primarily due to its excellent linear connectivity and capital-intensive seaside operations. However, as landside operations are riddled with extended cargo clearance times, excessive compliance requirements and lengthy waiting times for container pick-up and delivery, its performance stands below par against gateway ports. This not only significantly impacts the quality of service experienced by the thousands of customers who visit the port each day, but may also deter potential foreign investors looking to set up businesses in Sri Lanka.

A comprehensive three-year study conducted by a team of researchers from the University of Peradeniya and the University of Wollongong in Australia has now revealed a set of underlying factors that contribute to the poor landside operations performance of the Port. These factors, which are elaborated in this article, relate to the three key aspects of cargo clearance procedures, information-sharing protocols and the physical configuration of port facilities. The findings of the study also include possible short, medium and long-term solution pathways for addressing these factors towards achieving sustainable operational excellence.

Performance comparisons

Seaports form part of the critical logistical networks that facilitate international trade. Efficient and responsive logistics systems can make a substantial contribution to a country’s economy, in terms of revenue generation, employment creation and attracting foreign investment. In this regard, the Port of Colombo is of particular significance, largely due to its strategic location and the ability to accommodate larger vessels. It is a major hub port located in the midst of east-west shipping lanes and ranks among the top 30 global ports in terms of the number of containers handled.

According to the Container Port Performance Index (CPPI) published by the World Bank in 2020, it ranks at the 17th place out of 351 ports, earning it the status of the top-ranked port in South Asia. The port boasts of an excellent liner connectivity index, as well, meaning it is well connected to many other ports in the world through direct sailings. Being a transhipment hub, more than 75% of the cargo reaching the port is re-loaded to a different vessel destined to a port elsewhere in the world.

Australia, a country of continental proportions, has several large container ports such as Port Botany in Sydney, the Port of Melbourne, the Port of Brisbane and the Fremantle Port in Perth. These ports serve as gateway ports, meaning that they primarily handle export and import cargo. According to the World Bank study (ibid), Australian ports perform poorly in terms of the CPPI, placing the highest-ranked port in Australia, the Port of Brisbane, at the 246th place on the index. The top two ports in the word on this metric are Yokohama port in Japan and King Abdullah port in Saudi Arabia.

The CPPI is computed based on the time a ship spends at a port, commonly known as the vessel turnaround time, which largely depends on seaside operations. The time a ship spends at the port comprises waiting time to berth, berthing time, cargo operations time and waiting time to depart. Apart from the efficiency of seaside operations, several other factors, including the number of available berths, the number of vessels visiting the port, the size of the vessel, the number of containers exchanged at the port, and the number of cranes deployed to handle a vessel determine the turnaround time. While there are many factors at play, the differences in seaside performance of the Australian ports and the Port of Colombo can be largely attributed to the crane intensity or the number of cranes deployed per vessel. As a transhipment port, the Port of Colombo accommodates ultra-large container vessels frequently. As such, it is set up to quickly turn around vessels, with a large number of cranes servicing a vessel, so the berth can be allocated to the next incoming vessel within the shortest possible time. To the contrary, given the type of cargo handled and the nature of operations, Australian ports do not see the need to deploy a large number of cranes, which could be idling at times of low vessel traffic.

However, this comparative picture is reversed when the focus is on landside operations. A few metrics can be used to compare the landside operations performance of ports such as the truck turnaround time and the container release time. The truck turnaround time is the total elapsed time between a truck entering the port (after necessary pre-approvals) and exiting the port (after picking up or dropping off a container). In Australia, the average truck turnaround time is estimated to be 30 minutes, whereas it takes around 3 hours at the port of Colombo, showing a notable disparity.

‘Cargo release time’ measures the time it takes for an import container with commercial goods or personal effects to be cleared by the border control agencies. ‘Time-release studies’ published by the customs agencies around the world can be useful in this regard. According to the latest time-release study of Sri Lanka Customs, published in 2022, the release time for a full container load is 17.5 hours. However, upon closer inspection, it can be observed that the release time has been measured from the time an agent files a customs declaration until the container is released to the consignee. Given that the customs declaration is typically filed by an agent 3 days after the arrival of the vessel, the release time measured from the point of arrival of a container at the port could be even longer. Comparatively, in Australia, the release time is 2.4 hours from the time the container arrives at the port until it departs the port, showing a significantly better performance. The average release time from arrival to gate out in Singapore is 7 hours and 27 minutes (in 2020).

Factors affecting poor performance

These performance differentials on the landside can be attributed to several factors. They directly or indirectly relate to cargo clearance procedures, including the scheduling of container pick-up and delivery, information-sharing protocols and the physical configuration of port facilities. The extent of technology deployed across the different segments of the cross-border logistics system is another key factor that contributes to these performance disparities.

In Sri Lanka, unlike in Australia, the customs agency does not allow for filing of the customs declaration prior to the arrival of cargo at the port. The current practice is that the documents mandated for declaration, such as the delivery order (DO), can only be obtained from the ocean carrier upon berthing of the vessel at the port. Sri Lanka customs has moved towards digitalisation by allowing the customs declaration to be filed online. However, negating the advantages of digitalisation, subsequent to online filing, the importer or their agent must visit the customs office with physical copies of the original documents to obtain clearance.

Understandably, this requirement is aimed at minimising potential risks of fraudulent activities. Nonetheless, in terms of the logistics system performance, physical visits not only add to the lead-time but also generate a large amount of paperwork. Comparatively in Australia, the submission and the subsequent evaluation of the declaration are performed entirely online.

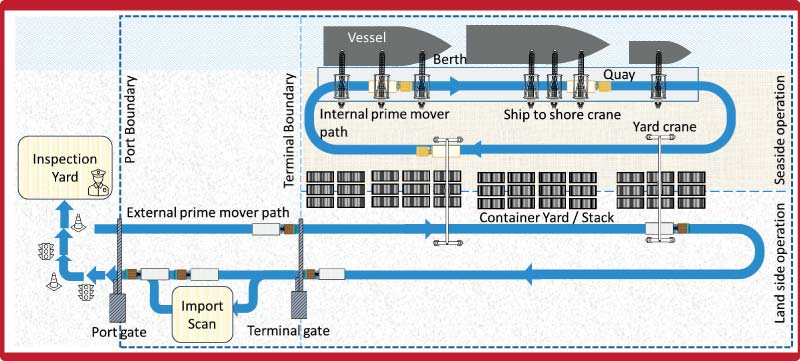

Another difference between the two cross-border logistics systems is the process followed by trucks visiting the port. Trucks visiting a port in Australia are required to obtain prior appointments following a schedule, thus minimising congestion. However, at the Port of Colombo, there is no such appointment system, and the vast majority of trucks enter the port in the afternoon. This is usually preceded by the customs clearance activities, which are performed in the morning. As a result, long queues in and around the port in the evening are a common sight. This is exacerbated by the procedure that the details of trucks, drivers and containers are compared manually against the gate passes issued by container terminals and customs at those gates. The customs house agent is also required to be present for this ‘clearance’ task. In comparison, there are automated smart gates at Australian ports where the details of trucks and containers are read by sensors, followed by the gates opening automatically.

Moreover, in Sri Lanka, once the container exits the port gate, the clearance process could continue further. Some of the trucks are required to visit a container inspection station located in congested areas of the city, which can take several hours to reach despite being only a few kilometres away. The capacity of these inspection centres is also limited, resulting in lengthy clearance times extending into many hours. Contrastingly, in Australia, inspections of containers are carried out prior to releasing it to the importer, with only the containers assessed as high-risk (as opposed to randomly selected containers) are subject to inspections. Therefore, once the container leaves the port, it is often released to the consignee with the exception of only a few containers requiring further inspection by the quarantine agency.

Several other differences can also be observed between the two systems. In Australian ports, there is a single gate, the gate of the container terminal that trucks have to cross to enter or exit the port. However, at the Port of Colombo, a truck needs to cross the port gate, which is considered the customs perimeter, after passing the terminal gate. There are duplicated checks done by authorities representing the relevant agency at each gate, which adds to lead-time while also causing inconvenience.

Additionally, in many cases, each agency operating at the border demands similar information at different points of time, thus exacerbating the compliance burden on importers, exporters and their agents. Most of these organisations, over time, have deployed their own information systems as part of their digitisation efforts. This has somewhat eased the submission process compared to paper-based processes. However, the information systems have often been developed independently resulting in the need to submit the same information multiple times still prevailing across the board. For example, exporters in Sri Lanka are required to submit overlapping information to customs, the shipping company, the port authority, the container terminal and the export facilitation centre. This is in addition to obtaining necessary clearances from agencies such as the National Plant Quarantine Service, Department of Animal Production and Health, Department of Import and Export Control and the Sri Lanka Tea Board, depending on the type of cargo involved.

As this is a rather common problem around the world, international organisations such as the World Trade Organization and World Customs Organization have recommended information systems known as National Single Windows (NSW), which replace multiple systems with a single centralised system. However, the implementation of NSWs has proven to be difficult, expensive and time-consuming for many countries, given the scale and complexity of such initiatives. Interestingly, despite having a highly efficient system for processing documents, Australia does not have a NSW implemented to date. Instead, it has developed a system using a ‘message broker’, to interface the pre-existing information systems of the individual agencies and has proven highly effective. This demonstrates that rather than adopting universal systems, countries are able to develop and implement solutions to suit local conditions.

|

Possible solution pathways

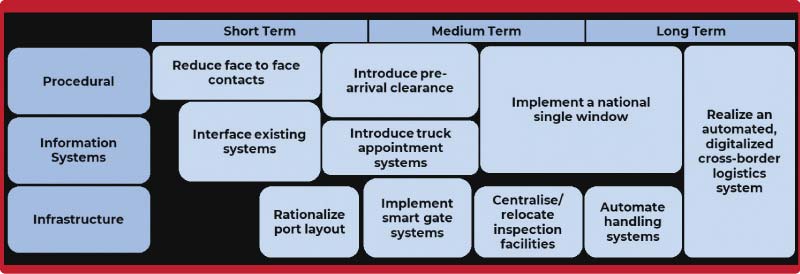

Having identified the key factors affecting the landside operations of the port and their underlying causes, several solution pathways can be proposed. For example, in regard to addressing procedural factors, there are opportunities for streamlining current protocols, in the short-term, for minimising face-to-face contacts and redundant interfaces without compromising the integrity of the system. Introducing pre-arrival clearance could be considered as a medium-term option, prior to adopting more substantial technology-driven solutions such as automated inspections or a fully on-line system, which may well be pursued in the longer run.

Although the factors related to information sharing are best addressed through data integration across multiple stakeholder platforms, as a short-term solution, incremental improvements are quite possible with higher-level interfacing at the functional level across the government agencies directly involved in the process. Given that large-scale infrastructure upgrades are long-term options to be considered at the whole-of-the-government level, options such as facility layout improvements, truck appointment systems and smart gates can all be explored as short-medium term options to reduce congestion and improve service levels.

Overall, in order to uphold the integrity of the cross-border logistics system, with respect to its core purposes, the proposed changes must be aligned with risk management best practices, as well. As such, long-term pursuit of digitalisation, as well as employee buy-in and leadership commitment to facilitate cultural shifts, are all critical aspects of achieving and sustaining operational excellence. Additionally, any formal evaluation of the proposed solution pathways should include standard tests such as technical feasibility, environmental impact assessment and benefit-cost analysis.

Considering that the Port of Colombo performs at the best practice level on seaside operations, there is a compelling case for improving landside operations, as well, to lift its overall performance. This is particularly important as the country aspires to attract foreign investment and given that two more container terminals are poised to start operations soon. As the nation attempts to re-build its economy, it is paramount to have a high-performing logistics system for imports and exports. The businesses and entrepreneurs striving to revive the economy can immensely benefit from having an efficient cross-border logistics system in place.

More detailed scholarly publication on this study, including more detailed solution pathways, can be found at https://rdcu.be/dVKIq.

(Dr. Namal Bandaranayake, a senior lecturer at the University of Peradeniya, is a logistics scholar and a senior project management practitioner with over 15 years of industry experience in multinational companies.)

(Dr. Senevi Kiridena, a senior lecturer at the University of Wollongong in Australia, is an operations strategy and supply chain management expert with over 20 years of experience in the industry, academia and the Australian public service.)

(Prof. Asela Kulatunga, a faculty member of the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom, is a senior scholar specialising in supply chain engineering, industrial systems, sustainable manufacturing and life cycle engineering.)