Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Monday, 30 March 2020 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The fate of the Kola Monara

The Sri Lanka Rupee appears to be experiencing a freefall for about a week now. According to the Central Bank data, on 27 March, the US Dollar had been bought by commercial banks, on average, at Rs. 187.10 per dollar and sold at Rs. 191.99.

This has pushed up the indicative exchange rate, the mid-rate of buying and selling rates, to Rs. 189.55, up from Rs. 187.63 a week ago and from Rs. 177.48 a year ago. It records a depreciation of the rupee, popularly known as the ‘Kola Monaras’ or Green Peacocks – an ingenious new name christened to rupee by the local folk taking into account the design and the colour of the Rs. 1,000 note – by 7% over the year and close to 4% from its level at end-2019.

This is not an acute ailment due to the closure of the economy by the Government to fight the menacing COVID-19. Rather it is a sign of a chronic ailment that had started in Sri Lanka many years ago, as I had argued in this column in the past.

Problem is insufficient forex earnings

Sri Lanka’s problem is that it does not earn enough foreign exchange to make our foreign exchange payments. The main earner of foreign exchange, merchandise exports, had been showing a sluggish improvement as from about 2011.

During 2011-19, the annual average merchandise exports had been $ 10.9 billion, almost equal to the annual trade deficit of the country in the recent past. To fill the gap, this has to be supplemented by other types of earnings such as sale of services, earning factor incomes and receiving remittances which the country gets from its migrant workers abroad. Sri Lanka’s sale of services to foreigners such as banking, shipping, insurance, tourism and ICT, etc. earns it a net income. However, on account of the heavy interest payments on foreign loans, its factor income is in the negative range. Sri Lanka’s migrant workers send every year a substantial amount of foreign exchange to the country but it has now peaked at about $ 7 billion per annum.

These earnings are insufficient to finance the massive trade gap. Hence, the country’s balance with the rest of the world on account of current transactions, recorded in what is called the current account in the balance of payments has resulted in a deficit, at about 3% of GDP per annum on average, requiring the country to borrow abroad or attract foreign direct investments to fill the gap.

The good news is that the trade deficit has shrunk to about $ 8 billion in 2019 from its peak at $ 11 billion in 2018 responding to the drastic policy measures taken by the Central Bank in that year. This has pushed down the current account deficit to slightly less than 2% of GDP in 2019. But it is still a deficit which has to be financed through borrowings since foreign direct investments have been a meagre supply.

Borrowing from commercial sources to repay loans

Despite the many favourable factors which Sri Lanka possesses such as an educated workforce and location on a convenient trade route, the country’s track record in attracting Foreign Direct Investments in the past had been far from the desired. In fact, they had been less than $ 1 billion, on average, per annum during 2011-19.

Hence, the full responsibility for filling the current account deficit had devolved on foreign borrowings which Sri Lanka had to make mainly from foreign commercial markets under non-concessionary terms. This was because its elevation from a low-income country to a lower middle-income country in 1997 which status disqualifies it to receive concessionary foreign borrowings.

But, since the country’s foreign exchange earnings had been inadequate, these borrowings had created a new problem in the form a foreign debt trap making it necessary for it to set aside a bigger amount of foreign exchange earnings to pay interest on and repay the maturing principal of foreign loans.

|

Today, the Sri Lankan Government is at a crossroads. Battered by the onset of COVID-19, both globally and locally, the Government cannot introduce long-term remedial measures to correct the situation. Hence, its fight today is for ensuring day-to-day survival. As such, it has no option other than making further borrowings to meet its oncoming foreign exchange commitments

|

The sale of the Bank’s gold reserve to generate liquid cash

In fact, how the country met this obligation in the past was to borrow more from foreign markets thereby adding more woes to its existing problems. For instance, in the next 12-month period, according to the Central Bank data, Sri Lanka needs about $ 5.8 billion to meet its foreign debt obligations.

But this is a challenging task given that the available liquid foreign exchange reserves have amounted only to $ 7.5 billion. They have been made liquid by selling the Bank’s gold reserves, according to its data, to the extent of $ 594 million in February and adding the sale proceeds to the freely available reserves. As such the gold reserves of the Bank now stands at $ 342 million at end-February, down from $ 936 million a month ago.

The track record of the rupee

As I said earlier, the rupee’s one-way journey has not been a new phenomenon. In 1947, just one year before independence in 1948, Sri Lanka rupee was exchanged for Rs. 3.32 per US dollar. In 1948, this was devalued to Rs. 4.78 per US dollar, taking into account the country’s specific situation as an independent nation with no backing by a colonial master.

Under the fixed exchange rate system which the country followed in the first two decades since independence, this rate was maintained till 1967. However, when the British Government unilaterally devalued its Sterling Pound by 20%, Sri Lanka also had to follow suit, since the United Kingdom was the country’s main trading partner with respects to its tea exports. Accordingly, the dollar-rupee rate was changed to Rs. 5.93 per dollar in that year. Since then, from time to time, the rupee was devalued both formally and informally. The formal devaluation pushed up the rate to Rs. 8.83 per US Dollar by 1976.

But this was a misleading rate since, informally, there was another exchange rate for the rupee for almost all imports and non-traditional exports at a higher level under a new system that had been introduced since 1967. This system was called Foreign Exchange Entitlement Certificate Scheme, commonly called FEECS.

Under FEECS, the rupee was traded at a premium of 65% over the formal exchange rate. Hence, for all practical purposes, in 1977 when Sri Lanka went for a flexible exchange rate system, the effective exchange rate was not Rs. 8.83 per US Dollar but Rs. 14.57 per US Dollar.

These systems were known as the multiple exchange rate systems and under the new reforms introduced in 1977, FEECS were abolished and the rate unified at a single rate of Rs. 15.56 per US Dollar. It therefore indicated only a depreciation of 7%. Since 1977, under the flexible exchange rate system under which it was the market forces that determined the fate of the currency, the rupee started its one-way journey of continuous freefall, ending at Rs. 189.55 per US Dollar as on 27 March.

Rupee’s one-way journey in graphical form

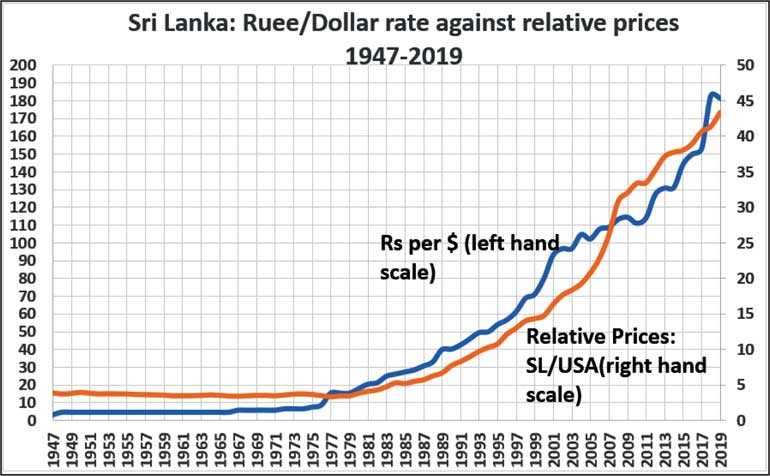

I have presented this story in Graph 1 drawn against the left-hand side scale. The line is more or less flat till 1976 but it is misleading since during that period there was a fixed exchange rate system coupled with multiple exchange rates.

But since 1977 in which year the country adopted a flexible exchange rate system, the rupee had been depreciating in the market steadily. The failure of the successive governments to arrest this development has been the worrying factor for many Sri Lankans.

The law of one price or Purchasing Power Parity

In this graph, I have presented another story. Its basis dates back to the Swedish economist Gustav Cassel who presented in 1918 that there could be one price in the world if the exchange rate gets adjusted according to the differences in the price levels among countries.

This is the famous Purchasing Power Parity or PPP theory now liberally used by all. Later in 1960s, the Polish-American economist Bela Balassa improved upon Cassel’s PPP by highlighting that even when there is free trade among nations, PPP would not be maintained due to non-tariff barriers to trade and the non-availability of services for trade among nations. Whatever these modifications, the basic tenet of PPP still remains valid.

Exchange rate gets adjusted to equalise prices

Cassel’s PPP could be illustrated by a simple example. Suppose a shirt in Sri Lanka is Rs. 100 and that in USA is $ 10. If the exchange rate is Rs. 100 per dollar, it is beneficial for Americans to bring one dollar, convert it to Rs. 100, buy one shirt and sell it for $ 10 in the US market. This activity of buying from the low-priced market and selling at the high-priced market for profit is called arbitraging.

Arbitrageurs will cause the prices in Sri Lanka to move up by creating a new demand for shirts and the prices in USA to move down by increasing the supply. This process will continue until there is no more arbitraging profits through a movement of local prices and in the exchange rate up to clear the market. That exchange rate would be, at the prevailing prices, Rs. 10 per US Dollar. At this exchange rate, there is no more incentive for Americans to buy shirts from Sri Lanka since he has to spend $ 10 for that purpose. At that price, he could buy a shirt from the US market itself.

Domestic inflation versus foreign inflation

What this means is that the main determinant of the exchange rate is the differences in the relative prices between countries. Accordingly, if the home country prices are higher than the foreign country prices, the local currency should depreciate to maintain PPP.

In the opposite, if the home country prices are lower than the foreign country prices, the local currency should appreciate against the foreign currency. Thus, if a country desires to maintain stability in the exchange rate, all it has to do is to maintain its inflation rate equal to foreign country inflation rate.

Sri Lanka’s higher inflation than in USA

The second story I have depicted in Graph I, measured against the right-hand side scale, is the relative price movement between Sri Lanka and USA. This curve should remain flat if prices are equal in both countries, should fall if Sri Lanka’s price changes are lower than those in USA and should increase if Sri Lanka’s price changes are higher than those in USA.

From 1947 to 1976, both countries had a similar price changes and therefore, the relative price curve has remained flat. During this period, the exchange rate too has been more or less stable, according to data on the formal exchange rate between Sri Lanka rupee and the US dollar. However, as explained above, this is a misleading conclusion since during this period, the exchange market was not stable as demonstrated by the need for resorting to exchange and import controls, on the one hand, and using multiple exchange rate practices, on the other.

From 1977 onward after the exchange rate was freed from the strict government controls, the rate has continued to depreciate almost one for one with the increase in price changes in Sri Lanka vis-à-vis those in USA. In other words, the culprit in Sri Lanka’s continued rupee depreciation has been the higher inflation rate within the country compared to USA.

The uncontrolled budget is also a culprit

There has been another culprit in Sri Lanka’s inflation fiasco. That is the uncontrolled Government expenditure programs needing it to finance the budget basically by using the funds available from the Central Bank in particular and the commercial banking system in general.

When the Central Bank prints money and makes it available to the Government to undertake its expenditure programs, such money known as the base money, will end up at commercial banks enabling them to create further money and credit.

Hence, financing the budget through the Central Bank’s printed money is highly inflationary. That inflation has caused Sri Lanka’s prices relative to those in USA to increase faster and in the process push down the external value of the rupee. These profligate public expenditure programs, irrespective of the justifications offered, have resulted in a continuous depreciation of the rupee in the foreign exchange markets.

The gloomy market scenario

Today, the Sri Lankan Government is at a crossroads. Battered by the onset of COVID-19, both globally and locally, the Government cannot introduce long-term remedial measures to correct the situation. Hence, its fight today is for ensuring day-to-day survival. As such, it has no option other than making further borrowings to meet its oncoming foreign exchange commitments.

But there are two impediments faced by the Government in this regard. One is that the present global financial market conditions do not offer the best environment for it to borrow. The other is that its credit ratings have been lowered and as a result, it cannot raise funds at the best rates available for a country of equal rating.

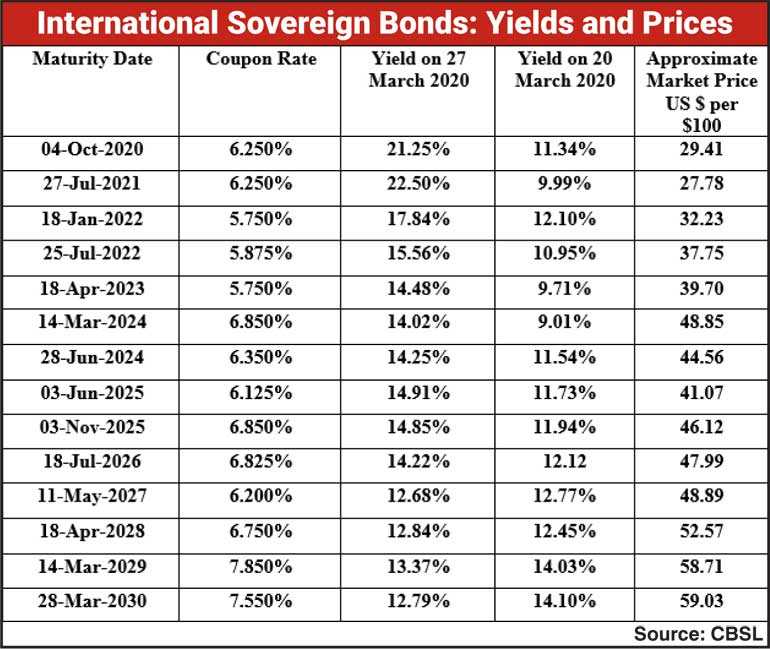

This is manifested by a sharp fall in the secondary market prices, or equivalently an unwarranted upward movement in their yields, of the International Sovereign Bonds or ISBs it has already issued. The gravity of the situation is demonstrated by the data issued by the Central Bank last week and presented in Table 1.

The sudden fall in the prices of International Sovereign Bonds

According to these market statistics, the bonds that are to mature in October this year has recorded a sharp increase in the yields from 11.34% to 21.25% within a week. The normal development in the market is that when a bond approaches its maturity, its market price tends to be close to its face value. But, in this case, the market price had fallen to $ 29 per $ 100 bonds indicating that the investors want to exit Sri Lanka at any cost.

The market conditions relating to Sri Lanka’s long duration bonds are not as alarming as short duration ones, but they do not offer the ideal situation for it to go to international markets for borrowing.

In the case of 10-year bonds, the high yield rates that were prevalent previously have slightly declined to 12.79%, indicating that investors are willing to exit Sri Lanka Government’s sovereign bonds at a deeply discounted price of $ 59 per $ 100 bond. What it means is that if Sri Lanka goes to the market today, to raise $ 100, it has to issue a bond at a face value of about $ 170. Needless to say that it would add more to the country’s existing debt stock.

The desperate sale of gold reserves

In these circumstances, the Central Bank has scraped the bottom of the bowl by converting a part of its gold reserves, estimated to be around 12 tons, into liquid foreign exchange balances. A country does so when it is desperate and there are no other viable options available. This is the first time that the Central Bank has resorted to this practice.

In India, Finance Minister Manmohan Singh who faced a similar catastrophic situation had to airlift 67 tonnes of gold from the Reserve Bank of India to London and Zurich to be pledged as collateral for a loan to be negotiated with IMF in 1991. However, Singh used the catastrophe to introduce a massive economic reform program which yielded amazing results for the country. Sri Lanka’s problem is that it has no space to do so in the current environment.

Unity rather than division is called for

Sri Lanka is surely going through the most difficult period in its history today. It is not a time for division among citizens on political, ethnic, language or religious grounds. Sri Lankans have to go through the severest economic hardships in the next three- to four-year time period and those hardships could be absorbed without feeling pain only if there is unity among the people.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected])