Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Friday, 27 April 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A lot has been said in the very recent past about financial inclusion, SMEs and micro finance and the inevitable debt trap, culminating with the statement by the Governor of the Central Bank that a National Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFIS) is to be put into force in mid-2019.

Whether this strategy will be all-encompassing to deal with the most vulnerable sectors of the economy, is left to be seen. The Governor has identified the key concerns of such a strategy, while the IFC which is involved in facilitating this strategy has recognised the need to customise it to fit the country specifics to make it a truly Sri Lankan strategy.

To commence this walk we must take the first step – come to terms with what we mean by financial inclusion. Is it banking penetration, access to institutional financial services, or access to affordable credit, for those who are currently excluded? It is worthwhile here to consider the ADB’s definition –“ready access for households and firms to reasonably priced financial services”.

The financially excluded are easily the most vulnerable sectors of the economy – those that are currently being exploited by the unofficial financial system that thrives alongside and runs in parallel with, the institutionalised, regulated, financial system, which, unfortunately, does not welcome the financially excluded.

The most crying need of those that are financially excluded to be able to get out of the stranglehold of the unofficial sources of credit that thrive on their misery. This then should be the focus of any FI strategy – to ensure ease of access to affordable credit to those who need it and who are currently excluded from the institutionalised, regulated sources of credit.

An essential pre-requisite of a policy on Financial Inclusion (FI) is a policy on Financial Literacy (FL).

FI without FL will lead to misuse of bank credit at a debilitating cost to the consumer. Financial ignorance is the new financial illiteracy with financial institutions focusing on the return and not on the risk, to lure consumers. The financial jargon that is so commonplace in product literature, misleading advertisements and publicity.

Is the loan documentation user friendly? Is it in the language of the borrower who, it is presumed, is, in the first instance, print literate? If they are not literate has the loan process been explained to and understood by the borrowers to their satisfaction?

One of the most critical components, in my opinion, is that a simple one page loan agreement in simple language should be developed for this sector that gives, at first glance, the most important aspects of the loan. To flaunt long-drawn out loan agreements for these facilities is meaningless and defeats the whole objective of FI.

On the other hand not to support these facilities with any documentation is equally bad, where loan officers are known to go out into the field with their tablet PCs to record the transactions for their own purposes. The borrower is completely in the dark about the details of the loan and his obligations for repayment.

This is the concern raised by the Governor of the Central Bank recently, about loan sharks operating online, over which there is little or no control. The emphasis on awareness is indeed paramount. Mystery shoppers can be employed to demystify these seemingly, easy to access, loan schemes to reveal the obvious scams that are floating around the system and which prey on the gullible consumers. Whilst we can do only so much to protect the public, as watchdogs of the financial system and in ensuring its integrity, we are duty-bound to expose unethical financial practices which exploit our people.

Even though the Central Bank does not have any control over lending schemes not funded by public deposits, it can step in to ensure and preserve the integrity of market conduct, through maximum disclosure on the modus operandi of these schemes, where the people are made aware of the cost of these easy-to-access credit schemes – the rate of interest – and the annual percentage rate payable. This is an imperative. If it can be done in the UK where the controversial Wonga.Com payday loans which charged as much as over 1,000% (APR) as interest were subject to regulation by the Financial Conduct Authority of the Bank of England.

Since July 2014, all payday loan companies have had to conform to new rules, which limit roll-overs of loans and force them to increase affordability checks. From January 2015, they were also to have their charges capped. On 2 October 2014, Wonga agreed to write off the debts – thought to total £ 220 m – of 330,000 customers who were in arrears of 30 days or more. This was a direct consequence of discussions with the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).

As has been often said, we must, perforce, translate our very high level of literacy, one of the highest in the world, from just print literacy, to financial literacy where Sri Lanka does not rank very well. Even countries like Bhutan have a much higher level of parity between print literacy and financial literacy.

Do they need bank accounts? I think not. Certainly not before they have acquired a basic level of financial literacy to be able to understand the benefits, if any, of a bank account where, invariably, excessive bank charges would devour their meagre bank balances as a result of administrative or transaction costs.

It is unthinkable that the low and middle income sectors of the population have the financial capacity to operate a current account, as a result of which Sri Lanka still remains largely a cash society. The testimony to this is the recent editorial of the FT on the subject, which pointed out that although 63% of Sri Lankan adults had a bank account, they remained underutilised with no deposits or no withdrawals, which points to the fact that a bank account serves no useful purpose to most Sri Lankans if they do not have the financial capacity to fund it, to be able to operate it.

These accounts will invariably become dormant accounts and certain banks which impose charges on minimum balances, would devour whatever there is left in these accounts as a result of the charges levied for balances which fall below the minimum specified balance. All any bank is concerned with is the administrative cost of maintaining these accounts which is one of the primary factors that contribute to the exclusion of those who are unable to maintain a minimum balance even in their savings accounts – which gives the banks imposing minimum balance requirements, a captive stable source of funds.

It is tantamount to giving a specific amount of your money free of charge to the bank for its use, just so as to be able to run that account at the bank concerned – i.e. the cost of your current account – in some banks it is as high as Rs. 7.5 million for a meagre rate of interest and of course the camouflage of all those frills they throw at you like the use of airport lounge services, etc., which would cost you much less if you paid for those services every time you needed to use them.

How many people have the financial capacity to give the bank the free use of such a large sum of their money? I fail to understand the logic of such patronage, just to be able to maintain an account at any particular bank. I may be naïve, but it certainly defies my common sense!

We have the example of the GFC which was the result of financial illiteracy of the consumer being exploited by the banks to the fullest – US Subprimes – Who were the losers? The banks were bailed out, but the consumers lost their homes – foreclosures were the order of the day across the US and in Europe.

Why? The documentation was clearly in favour of the banks – borrowers did not realise that the banks were luring them into debt even though they were not creditworthy, as they were securing the credit risk they were clearly taking, with the mortgaged property which meant that borrowers would be thrown out of their homes at the first sign of delinquency.

The banks lost nothing. The system clearly lacked accountability. We must ensure that the banks play a major role in their commitment to FL in the interests of fostering a responsible banking culture. The GFC was all about irresponsible banking.

Most banks have made definite efforts at enhancing financial literacy but who are they targeting? And is this enough?

We need to reach the grass roots – those that are most vulnerable. How much of the literature is in a language of the mass market – what the population are comfortable with? Markets differ from country to country, so the same degree of disclosure as other markets, will not suffice. We need to cater to our own, specific, markets and needs.

Microfinance, the debt trap and responsible finance

One of the most critical components of any FI strategy would have to be irresponsible finance practised by the so-called unregulated microfinance institutions and, indeed, under the micro finance schemes run by the regulated, banks and non-bank financial institutions.

Today microfinance has emerged as the most lucrative source of profit for most financial institutions, entirely at the expense of the middle and low income sectors of the population who are classified high risk, which risk premium is built into the exorbitant interest rates charged for loans disbursed to this sector.

The scourge of microfinance has been building up over the last five years at least and even though the statistics are obviously available at the Central Bank of this build up, particularly in the non-bank finance companies sector, no action has been taken to address the glaring debt trap that consumers of micro finance have been unwittingly caught up in and to nip the problem in the bud.

The microfinance legislation that finally saw the light of day sadly didn’t fit the bill and is a piece of legislation so laboriously crafted to cover only about 10 so-called MF institutions which fall into the definition of MF by virtue of the minimum capital specified (Rs. 100 million). Even the microfinance schemes of the banks and the non-bank finance companies do not come within the ambit of this legislation and largely remain unregulated in this market segment.

More profoundly, the myriad MF institutions that abound in the unofficial financial system, remain unregulated and have a free ride at the mercy of the consumers of MF whose woes remain appallingly unresolved.

The recent FT editorial on MF and the debt trap talked of the unbelievable plight of the consumers in the north who were assailed with MF after the war to meet their desperately critical credit needs and whose plight was allowed to be exploited through irresponsible credit schemes developed by financial institutions, obviously at an unaffordable cost, which resulted in their inability to service these debts.

Even the Governor of the Central Bank personally led a team of officials to examine this problem in the north. It is apparent that the low level of financial literacy of this highly-vulnerable sector was exploited to the hilt, by irresponsible finance and banking and no amount of sustained growth in the post-war climate, would help to alleviate the obvious debt trap they had fallen into, where the cost of credit was in the region of 40 to as much as 70%! Where in the world could anyone earn enough to be able to service such costly credit, except through drugs and other criminal activity?

What did the cash flow analysis of credit officers reveal, if indeed any cash flow analysis was undertaken? Were the monthly repayments of these loans within the income-generating capacity of the borrowers or, where they were obviously not, were they granted against security such as property or gold, jewellery and other valuables?

There is no statistical information on the quality of the loan portfolios of the financial institutions in the north and east, which if there was, would be very revealing on the overall quality of credit administration in these areas, the cost of credit disbursed, etc.

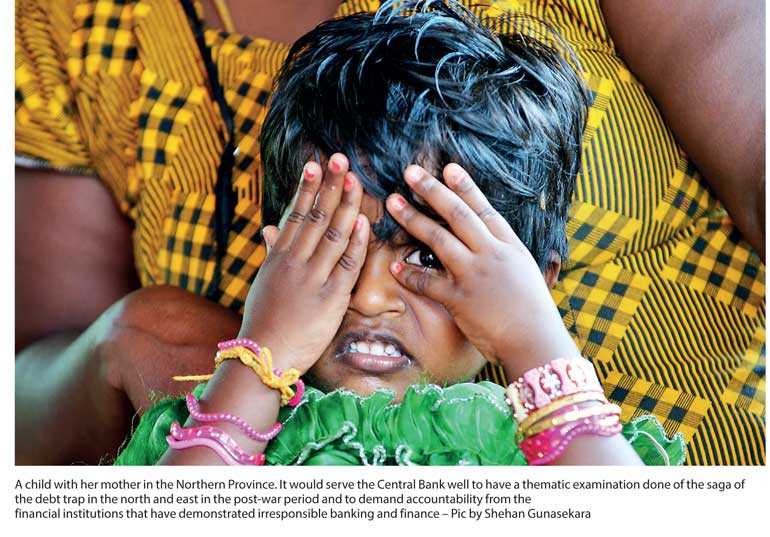

It would serve the Central Bank well to have a thematic examination done of the saga of the debt trap in the north and east in the post-war period and to demand accountability from the financial institutions that have demonstrated irresponsible banking and finance. It is reported that the hire-purchase schemes sold to financially illiterate borrowers in the north, primarily for consumption credit, were at the root cause of this huge debt trap they have unwittingly got themselves into.

The question that looms large here is: What are these MFIs? Are they licensed MFIs or spurious lending agencies that operate freely in the system, and which prey on the vulnerable low-income groups of people. Are there any statistics on the number of MFIs that operate in the financial system outside the regulated system? This then is the challenge for any FI strategy to identify and eliminate these vultures in the system, which is key to the success of the FI strategy.

The delayed action by the Central Bank to monitor the lack of responsible banking and finance that prevailed in the north has now resulted in the demand for a moratorium on these debts and the demand for a maximum rate of interest of 25%. While the moratorium is entirely justified, the maximum rate of interest even at 25% is far too excessive and must reflect a reasonable margin over the cost of funds.

To service a debt at 25% one has to get a return from whatever economic activity that is engaged in, of at least 30%. I am not sure that this sector of the population are engaged in that type of lucrative business to be able to generate such an attractive return and are, on the contrary, already toiling hard to even bring some food to the table for their families.

This is indeed a very sad state of affairs, when on the other hand, one reads of the financial results of almost all the banks and the finance companies, where profits have doubled and trebled, but very little is said of how these glossy results were generated, particularly when growth rates and GDP growth rates are in the doldrums.

I think it was MTI’s Hilmy Cader who said that even when there is an economic downturn, the banks and financial institutions are able to show an increase in profits! This would indeed be a very interesting study to undertake to see from where these profits are being generated, obviously from the high level of unproductive, consumption credit that is being disbursed, and classified as personal loans, which attract very high rates of interest.

The level of productive credit disbursed by the financial system just has to be reflected in the level of economic growth in the country. It is therefore imperative that the Central Bank begins to compute the all-important level of household debt in the economy vs. business finance.

It is alleged that even property loans are granted as personal loans and evade classification under the property sector. The several sub-classifications under household debt will surely be very revealing of the extent to which households are engaging in financing property, vehicles, consumption, education and other granular information which is currently not available. Whilst not undermining the financial system, it is imperative that every effort is taken to encourage responsible banking and finance and to ensure that the vulnerable sectors are not exploited as a result of their financial illiteracy.

The commitment that is evident from the Governor of the Central Bank and even from Government, to deal with the huge debt trap that has been facilitated by an unbridled, unregulated microfinance sector in this country, must be translated into action by identifying the gaps in the system that have escaped the attention of the authorities and by addressing them in a positive manner, to deliver positive outcomes.

It must be recognised that, while the problem of the debt trap is very acute in the north in the post-war scenario, microfinance is also rampant in the south and in other parts of the country where the same concerns prevail.

(The writer is the former Director of Bank Supervision and Adviser to the Governor at the Central Bank of Sri Lanka and freelance writer and independent consultant on financial regulation.)

The National FI strategy must, perforce, address the following issues if it is to be successful:

Flowing from the Government’s policy on mandatory credit, I wish to reiterate that the FI strategy should encourage credit accessibility with schemes that will encourage productive credit which will provide a win-win situation both for the consumer as well as for economic growth.

Will the President’s recent direction to the State banks, to disburse 100 loan schemes to the SMEs, have the commitment necessary to ensure that these loans are not treated as Government hand-outs, but are disbursed through carefully-designed credit programs catering to identified agricultural and industrial projects, which will ensure a sustainable source of income, adequate to service the loans and to generate a surplus for the consumer, instead of being a burden on the State banks, which are already saddled with so much development lending to SOEs, not to speak of financing the Government’s current account?

It would have been much more effective and equitable if these 100 loan schemes were distributed, if not amongst all the banks, both commercial and specialised, at least amongst all local banks. It’s not too late for the President to extend this scheme to the private sector banks as well. The report to the President would indeed be an interesting read.