Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Thursday, 15 December 2022 03:26 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Fiscal consolidation efforts may lead to an economic contraction with reduced household consumption and private investment

The Sri Lankan economy has been plagued by structural deficits in the fiscal balance and external current account for several decades and these deficits were aggravated with the COVID-19 pandemic. While the COVID-19 pandemic triggered an economic shock of unprecedented level across all countries, it was a tipping point for Sri Lanka to fall into the current economic abyss due to the worsened twin deficits in the fiscal and external fronts. At present, Sri Lanka is in a perilous state of macroeconomic instability with intensified vulnerabilities in all sectors of the economy.

Successive governments of Sri Lanka have been living beyond their means for decades, resulting in wide fiscal deficits, continual heavy borrowings from both the domestic and foreign markets, and debt accumulation over the years. Since its independence, Sri Lanka has recorded fiscal surpluses only in 1954 and 1955 (owing to the benefits gained from the ‘Korean boom’), highlighting the issue of persistent fiscal imbalances. The perpetual fiscal imprudence has culminated in an unsustainable level of public debt, compelling the Government to pre-emptively default selected debt service payments since April 2022 and resort to a process of debt restructuring. Although debt restructuring may alleviate fiscal stress in the near term, Sri Lanka is in a dire need of adopting strong fiscal consolidation measures to establish long-term fiscal sustainability and resolve macroeconomic imbalances that are emanating from persistent fiscal deficits.

Fiscal imbalances in Sri Lanka

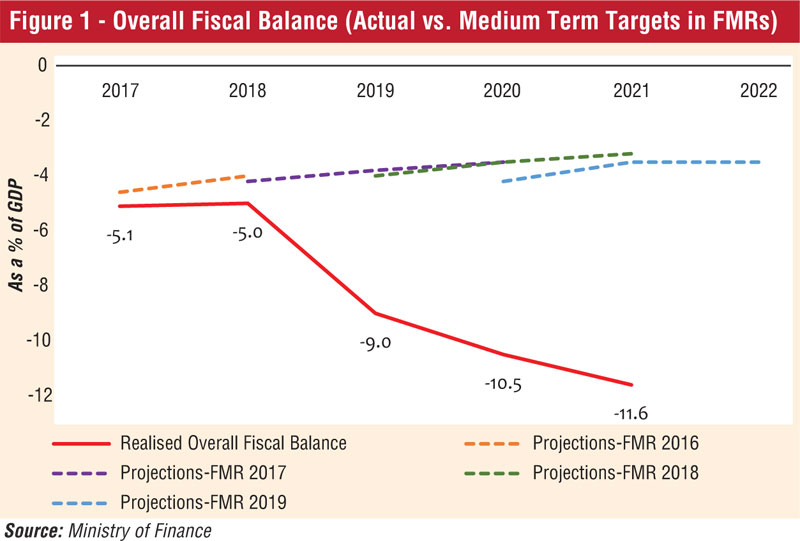

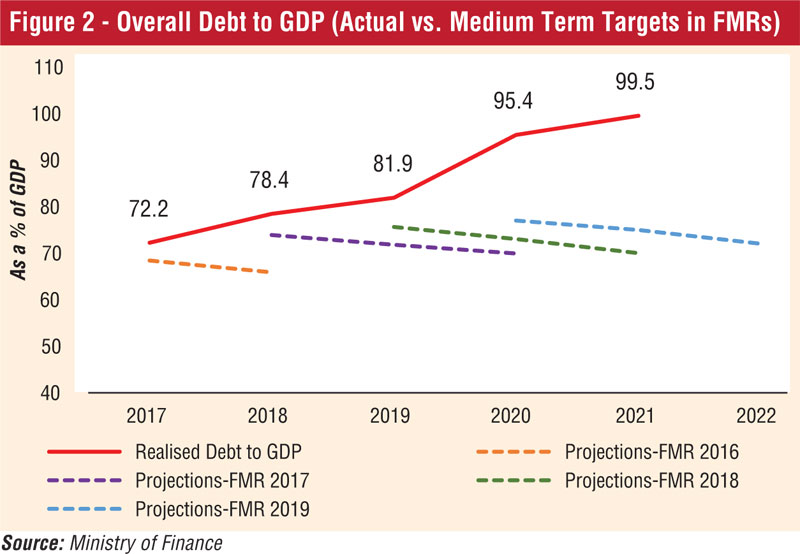

Sri Lanka’s fiscal landscape has been characterised by regular revenue slippages and expenditure overruns that have resulted in perpetual fiscal deficits and high government debt levels. The budget deficit and government debt targets presented in the Medium Term Macro Fiscal Framework (MTMFF) as per the Fiscal Management Reports (FMRs), which are published along with the Annual Budgets, have never materialised in the past due to overly optimistic revenue targets, inadequate revenue enhancement policies, rigid government expenses, and inefficient state-owned business enterprises (SOBEs) that required capital infusions time to time. Figures 1 and 2 show the deviations of the actual budget deficits and central government debt levels from the projections specified in the FMRs.

Meanwhile, fiscal imbalances were further exacerbated during 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic induced economic downturn and the changes in fiscal policy stance in late 2019 and 2020. Although the downward revisions to taxes introduced at the end of 2019 and early 2020 were intended to boost economic activities and thereby raise government revenue, in contrary to the expectation, revenue declined sharply in the past two years. Revenue as a percentage of GDP fell to the historically lowest levels of 8.7% and 8.3% in 2020 and 2021, respectively. Following the notable revenue decline, the fiscal deficits in 2020 and 2021 increased to 10.5% and 11.6% of the GDP, respectively.

Consequences of persistent fiscal sector imbalances

A government may pursue countercyclical fiscal policy and temporarily opt for deficit spending during periods of economic downturns with the aim of reviving the economy, though perpetual fiscal deficits could have adverse and lasting spillover effects on the real, monetary, financial, and external sectors. Except in 2020 and 2021, during which domestic interest rates were maintained at a historically low level, Sri Lanka generally had a high interest rate structure due to heavy government borrowings. Usually, large government borrowings result in crowding out of private investments due to high cost of borrowing for the private sector, thereby hindering long term economic growth.

Alongside the Central Government, the SOBEs had also contributed to the expansion in public debt through their excessive borrowings due to stalled institutional reforms in relation to pricing strategies and efficiency improvements. Persistent fiscal deficits could lead to deficits in external current account through increased imports, and this phenomenon was evidenced in the Sri Lankan context as well (Perera & Liyanage, 2012; Saleh, N. Mehandhiran, & Agalewatte, 2005).

When domestic resources are limited, governments tend to borrow from overseas to finance the budget deficit, raising future foreign debt service payments and external current account deficit. When Sri Lanka graduated from ‘low income country’ to ‘lower-middle income country’ status, the access to concessional foreign financing gradually became limited, compelling the Government to borrow at market interest rates from the foreign sources. Heavy borrowings from foreign commercial sources have raised the country’s debt service burden notably in recent years.

With the onset of the pandemic, foreign flows to the country moderated and thereby aggravated the economic woes created by the fiscal sector imbalances. A series of sovereign credit rating downgrades for Sri Lanka was triggered by the tax revisions in 2019 and 2020, in view of large debt service payments falling due in the near to medium term amidst low revenue mobilisation due to tax cuts and weakened external buffers. These rating downgrades further barred foreign financing avenues for Sri Lanka, compelling the Government to resort to domestic financing of the budget deficit, especially through the Central Bank and the banking system.

Since government revenue collection in 2020 and 2021 was not sufficient to cover even rigid government expenses such as salaries and wages, pension, and interest payments, the budget deficit was financed mainly through monetary financing in an attempt to ensure the smooth functioning of government operations. Unprecedented level of monetary financing of the budget deficit in the past two years has challenged the effective implementation of monetary policy and has imposed a heavy toll on all economic activities due to the sharp rise in inflation.

Continued heavy borrowings by the Government and the SOBEs have resulted in tight liquidity conditions in the domestic financial system, in terms of both domestic and foreign currencies. At the same time, the over-reliance of the Government and SOBEs on state banks and the weak credit ratings of these financial institutions have posed a challenge for the state banks to source additional foreign currency funding from domestic and foreign counterparts or to roll-over existing funding facilities. Amidst inadequate foreign currency inflows, tight forex liquidity conditions in the financial system, and foreign currency outflows on essential imports, the large external debt service payments of the Government in the past two years were made at the expense of foreign reserves, leading to a depletion of gross official reserves to a dismal level.

Consequently, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka had to allow measured adjustments in the exchange rate in early March 2022 in consideration of intensified currency depreciation pressures owing to dried up liquidity in the domestic foreign exchange market. Since then, the exchange rate has depreciated sharply due to market forces, triggering a further acceleration in domestic inflation. This exchange rate depreciation also raises government expenditure considerably, mainly through the increased foreign interest expenditure. At the same time, the foreign currency liquidity crunch in the domestic financial system has limited the imports into the country, creating prolonged supply shortages, regular power outages, and slow-down in most economic activities.

Accumulation of public debt is inevitable with the perpetual fiscal deficits and the persistently loss making SOBEs. As the public debt in Sri Lanka has reached an unsustainable state, the Government has been compelled to restructure the external debt to flatten the debt trajectory and reduce debt service payments to a manageable level. Although debt restructuring could bring temporary reprieve for Sri Lanka in terms of debt service payments, narrowing the budget deficit and maintaining a primary surplus through fiscal consolidation measures remain critical in the medium to long term to ensure long lasting fiscal and debt sustainability in the country.

Fiscal consolidation

The government policy aimed at reducing budget deficit and government debt is known as fiscal consolidation. This can be achieved either through (a) revenue enhancement measures such as tax increases or (b) measures for restraining expenditure or (c) both types of measures. Although fiscal consolidation supports fiscal sustainability in the medium to long term, policymakers may have concerns on the short-term costs of fiscal consolidation measures in terms of economic contraction and increased income inequality, especially during a period of economic downturn following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Generally, tax hikes and fiscal expenditure cuts could result in lower disposable income of households as well diminished after-tax profits of businesses in the short run. Consequently, fiscal consolidation efforts may lead to an economic contraction with reduced household consumption and private investment. In addition, fiscal consolidation may have distributional effects, leading to higher inequality within the population. Increase in indirect taxes or spending cuts on subsidies and transfers could have disproportionate negative consequences on low-income households (Ball, Furceri, Leigh, & Loungani, 2013). Since low-income earners must spend a large fraction of their income on consumption of essential goods and indirect taxes are generally passed on to consumers, the burden of indirect taxes on essentials is higher on low-income households.

Nevertheless, given that current macroeconomic vulnerabilities and unsustainable debt levels in Sri Lanka are stemming from long-term fiscal imbalances, the country has reached a critical point where there is no alternative other than fiscal consolidation to bring about macroeconomic stability. A sustained reduction in fiscal deficit is imperative to reduce the need for monetary financing and ease inflationary pressures while resolving liquidity shortage issues in the domestic financial markets. With reduced borrowing requirements of the Government, the market interest rates could possibly decline in the medium term, enabling the private sector to borrow at a lower cost and expand their businesses.

Therefore, fiscal consolidation is envisaged to support economic revival in the medium term, though there can be short-run contractionary effects. At the same time, successful debt restructuring negotiations will be conditional on the Government’s fiscal consolidation efforts, since external creditors would expect domestic fiscal sustainability that will ensure debt repayment capacity of the country in the medium to long term. Further, improved fiscal performance and debt sustainability are paramount to improve investor confidence and to unlock foreign financing avenues once again.

Economic and price stability in the domestic market and the rebound in foreign inflows are expected to ease the depreciation pressure on the exchange rate. Therefore, overall benefits of pursuing a fiscal consolidation path to achieve fiscal sustainability would outweigh any short-term costs to the Sri Lankan economy. Although tax increases and government expenditure cuts may not be politically and socially popular policies in the short term, any postponement in fiscal consolidation could create massive cost to the overall economy in the medium to long term. However, fiscal consolidation measures should be designed in a manner to minimise short term output effects and distributional effects, given that Sri Lanka is forging a fiscal consolidation path in the aftermath of several major economic shocks such as Easter Sunday attacks and COVID-19 pandemic.

Revenue-based fiscal consolidation

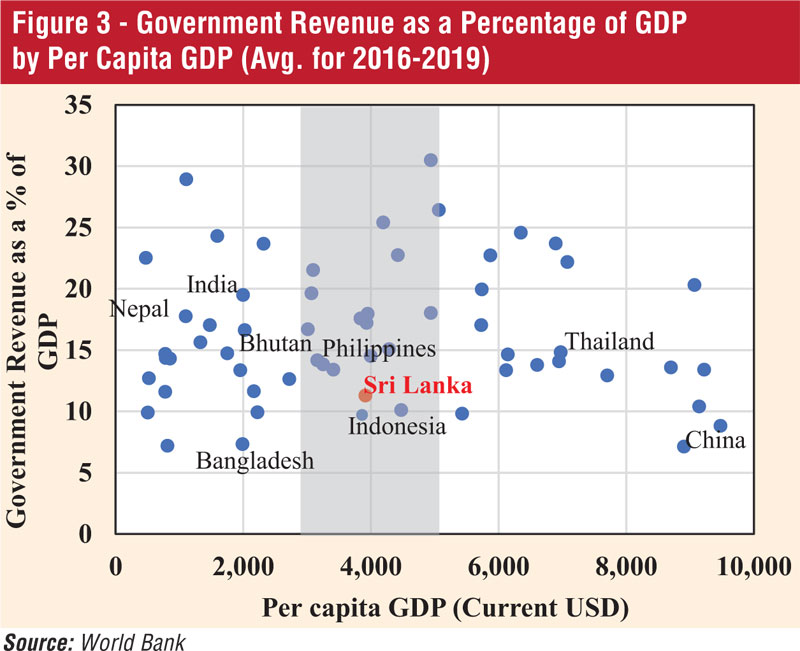

Revenue collection in Sri Lanka, which were at dismal levels in the recent years, leaves more room to achieve fiscal sustainability through revenue-based fiscal consolidation measures. Despite the gradual increase in per capita GDP, revenue mobilisation has not kept pace with economic growth in Sri Lanka as reflected in the country’s tax elasticities1 which are less than one (Indraratne, 2003). Figure 3 presents cross country data on revenue as a percentage of GDP against per capita GDP of the countries. The Figure 3 indicates that Sri Lanka has one of the lowest revenue mobilisation rates in comparison to economies of similar level of income, thus demanding prompt policy responses.

Low revenue mobilisation in Sri Lanka can be attributed to narrow tax bases, tax concessions that have neither generated higher economic activity nor increased the level of economic complexity, lack of progressivity in tax structure, and weak tax administration. In 2019, income tax free allowance for individuals was revised upward to Rs. 3.0 million per annum (around Rs. 250,000 per month), resulting in a significant erosion in tax base. As per the Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2019, the median income of income receivers that belong to the highest income decile is Rs. 115,000 per month, indicating that less than 5% of the income earners in the country were liable to pay individual level income taxes (Advance Personal Income Tax/Pay As You Earn tax/Personal Income Tax).

At the same time, upward revision of Value Added Tax (VAT) registration threshold in 2020, from Rs. 12 million per annum turnover to Rs. 300 million turnover per annum, eroded the VAT base. Recent efforts by the Government in revising the tax free threshold for personal income taxes and VAT registration threshold to Rs. 1.2 million per annum and Rs. 80 million turnover per annum, respectively, are aiming at expanding the tax base.

A large fraction of income earners in Sri Lanka is not within the tax net due to the sizable informal sector and high level of tax evasion due to weak tax administration. Therefore, broadening the tax base and improving the tax administration are crucial to raise government revenue in line with the growth in economic activity and income levels. This could enable the Government to raise government revenue by distributing the tax burden over a large tax base, instead of raising the tax rates notably and thereby imposing a substantial tax burden on businesses and individuals who are already paying taxes. In this regard, encouraging compulsory tax registration and augmenting human and physical resources for revenue collection, regular audits and bribery/corruption control measures for revenue collection agencies are essential to reduce tax evasion.

Further, linking the revenue collection agencies with the financial institutions, financial markets, and immovable and movable property registration offices are necessary to identify high-income earners and pursue tax collection from the same. It has been proposed by the Interim Budget 2022 to introduce compulsory tax registration for all who are aged above 18 years, irrespective of their income levels and tax free threshold, though expeditious actions are needed to make this proposal a reality. In addition, provision of tax concessions to businesses through evidence-based policies in the future and revisiting the existing tax concessions are critical to increase the corporate income taxpayer base.

Improving the doing business environment and trade facilitation would bring more broad-based benefits to businesses and the economy instead of granting tax concessions and tax holidays for few selected businesses. Moreover, simplifying the tax structure and tax filing process as well as encouraging electronic tax filing could help improving tax compliance of the taxpayers.

Over 75% of the tax revenue in Sri Lanka is generated from indirect taxes indicating the lack of progressivity in the tax structure and a relatively higher tax burden on low-income households. Therefore, gradual shift from indirect taxes to direct taxes is crucial to ensure equity in the tax structure. Capital gains taxes at the personal and corporate levels could have minimal output and inequality concerns. In addition, inflation indexation of excise duties, especially on cigarettes and liquor, is also needed in the period ahead to raise government revenue in tandem with nominal GDP growth.

Expenditure cuts-based fiscal consolidation

Fiscal consolidation based on expenditure cuts could be a challenge in the Sri Lankan context, since rigid government expenses account for a larger fraction of the overall government expenditure. For example, 61.4% of the total expenditure in 2021 was allocated on salaries and wages, interest expenses, and pension payments. Given the stringent labour contracts in the domestic labour market, a cut in salaries and wages or layoffs may not be an easy task and could be socially unpopular and politically costly. However, the growth in wage bill can be contained by avoiding large scale government sector recruitment that are not in line with the cadre requirement and restricting salary increments that are not validated by productivity enhancements.

At the same time, better targeting of subsidies and social safety nets and encouraging beneficiaries to gradually exit the safety nets programs through livelihood development projects are essential to rein in government expenditure. In addition, debt restructuring, which is already in progress, is also crucial to reduce near-term interest cost burden of the Government. Further, prioritising capital expenditure projects and postponing ‘low value adding’, non-urgent capital projects as well as trimming the unproductive and unnecessary recurrent expenses could reduce government expenditure considerably.

However, it should be noted that a cutdown in capital expenditure projects, especially in relation to social infrastructure such as health and education, could have serious growth and distributional implications in the medium to long term. Since SOBEs also add a significant burden on government budget, long overdue institutional reforms should be implemented without any further delay. Continuation of cost reflective pricing mechanisms for utilities through regular price revisions in a transparent manner, improving accountability and transparency in the SOBE management, and institutional reforms for market orientation and cost reduction are critical in this regard.

Way forward

Despite the pressing need for implementing fiscal consolidation measures in the past, successive governments have not shown strong commitment for fiscal consolidation, probably due to perceived economic and political costs in the short run. However, amidst mounting macroeconomic vulnerabilities, fiscal consolidation is the only feasible option for Sri Lanka to achieve fiscal sector sustainability and lasting overall economic stability. Sri Lanka is currently engaging with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to implement a comprehensive macroeconomic reform programme, in which fiscal consolidation strategies are a key component.

Accordingly, the Government has already taken several measures in relation to revenue enhancement and expenditure rationalisation with the aim of resolving current macroeconomic crisis, but these measures need to be augmented further and implemented with a strong commitment to achieve the desired outcomes, particularly in relation to the Government’s medium term primary balance target of 2% of the GDP by 2025 as indicated in Budget 2023. In addition, the Fiscal Management (Responsibility) Act, No. 3 of 2003 (FMRA) has stipulated fiscal rules2 pertaining to fiscal deficit, public debt, and contingent liabilities of the Government, though the rules are not binding rules.

However, strict adherence to these fiscal rules, with appropriate revisions to the rules, is important in the period ahead to ensure responsible fiscal management, prudent public debt management, and scrutiny of fiscal matters by the general public. At the same time, fiscal consolidation strategies should be formulated in consideration of output and distributional effects, to reap expected fiscal outcomes with the lowest short-term economic costs. Well targeted relief measures, possibly funded through the support of multinational agencies, may be required at least during the initial phases of fiscal consolidation to ensure most vulnerable households and individuals are not overly distressed by the economic crisis and consolidation measures.

Meanwhile, the success of fiscal consolidation measures is contingent on the vision of policymakers, commitment of all government institutions as well as the support of the general public. Hence, fiscal prudence, improving transparency in government finances and ensuring accountability of the government authorities are critical to maintain a tight rein on fiscal balance and to gain taxpayers’ cooperation for the fiscal consolidation process. In addition, an effective public communication strategy of the Government is paramount to garner the support of all stakeholders to implement fiscal consolidation measures in order to achieve long-term fiscal sustainability.

Footnotes:

1Tax elasticity is the inherent responsiveness of tax revenue to GDP assuming no changes in the tax structure.

2Fiscal rules are longstanding controls imposed on fiscal policy in the form of numerical limits on fiscal aggregates such as budget deficit, primary balance, and public debt.

References:

Ball, L. M., Furceri, D., Leigh, D., & Loungani, P. (2013). The Distributional Effects of Fiscal Consolidation. IMF Working Papers, 2013(151).

Indraratne, Y. (2003). The Measurement of Tax Elasticity in Sri Lanka: A Time Series Approach. Staff Studies, Central Bank of Sri Lanka, 33(1-2), 73-100.

Perera, A., & Liyanage, E. (2012). An Empirical Investigation of the Twin Deficit Hypothesis: Evidence from Sri Lanka. Staff Studies, Central Bank of Sri Lanka, 41(1), 41-87.

Saleh, A. S., N. Mehandhiran, N., & Agalewatte, T. (2005). The Twin Deficits Problem in Sri Lanka: An Econometric Analysis. South Asia Economic Journal, 6(2), 221-239.

(The writer is Senior Economist, Economic Research Department, at the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any institution.)