Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Thursday, 7 December 2023 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The way forward would be to determine VAT rates, thresholds and exemptions based on scientific analysis and clear economic rationale

Sri Lanka urgently needs to intensify revenue collection for macroeconomic stability and more inclusive and sustainable growth. The recent economic crisis was partly triggered by the systematic erosion of the tax base. Sri Lanka’s tax to GDP fell to 7.3% of GDP one of the lowest in the world. One of the main pillars of the IMF’s stabilisation program is to raise this ratio to 14% by 2026. There is empirical evidence to suggest that countries move to a higher growth path once tax revenue reaches around 15% of GDP.1More quality spending on education and health is required to build better human capital, while increasing poverty requires stronger safety nets. All this requires more revenue to be collected.

Sri Lanka urgently needs to intensify revenue collection for macroeconomic stability and more inclusive and sustainable growth. The recent economic crisis was partly triggered by the systematic erosion of the tax base. Sri Lanka’s tax to GDP fell to 7.3% of GDP one of the lowest in the world. One of the main pillars of the IMF’s stabilisation program is to raise this ratio to 14% by 2026. There is empirical evidence to suggest that countries move to a higher growth path once tax revenue reaches around 15% of GDP.1More quality spending on education and health is required to build better human capital, while increasing poverty requires stronger safety nets. All this requires more revenue to be collected.

Failure to reach the revenue target for 2023 delayed the release of the second tranche under the IMF’s Extended Fund Facility. Budget 2024, expects to raise tax revenue as a percentage of GDP to 12.1% from the estimated collection of 9.2% in 2023. In nominal terms, this is a 47% increase in tax revenue to Rs. 3.9 trillion. Of this, more than one-third is expected from Value Added Tax (Rs. 1.4 trillion). While Budget 2024 outlined several administrative measures to strengthen tax revenue collection, the main increase is proposed from changes to the Value Added Tax (VAT). From January 2024, the VAT rate will increase to 18% from 15%, the tax free threshold will be reduced to Rs. 60 million from the current Rs. 80 million and 87 out of 137 items will be removed from the exemption list.2

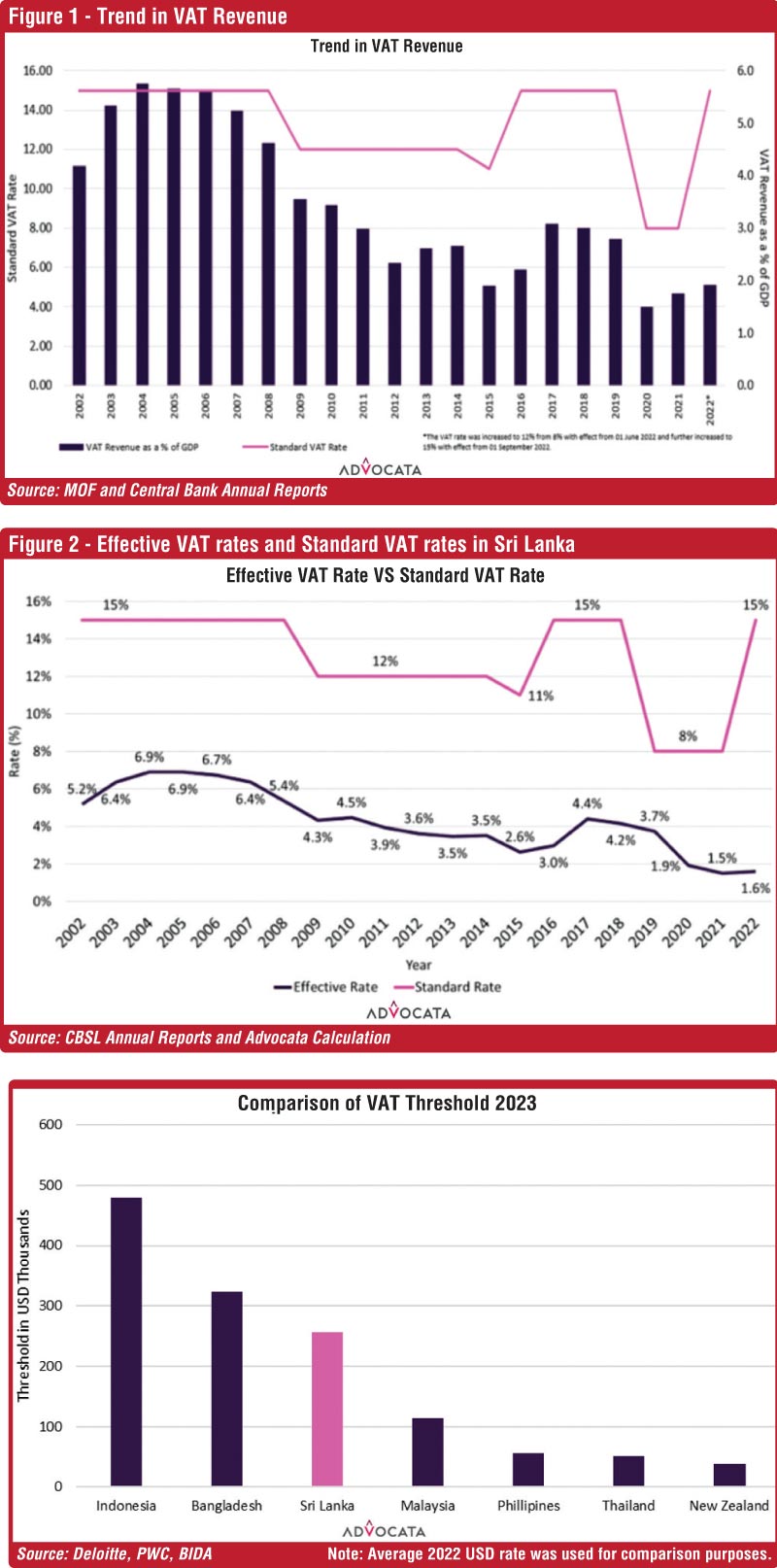

VAT is adopted by more than 160 countries, accounting for over 30% of their total tax collection. As a share of GDP, it accounts for around 4% in low-income developing countries and more than 7% in advanced economies.3 In Sri Lanka, VAT revenue as a percentage of GDP peaked at around 6% in 2004 but has since declined to 2% in 2022. Ad hoc policy changes and weak tax administration have eroded the tax base and reduced revenue collected from the VAT.

A close examination of the performance of VAT in Sri Lanka since its adoption in August 2002 highlights the challenges in implementing VAT in Sri Lanka.

Trends in VAT revenue in Sri Lanka

Analysing the trends in VAT revenue collection over the last two decades shows the impact policy changes have had on revenue collection. In 2013, 2016, 2017 and 2018 there was a significant increase in VAT revenue collection. It is not coincidental that these years saw several policy measures introduced to increase VAT revenue.

Measuring performance of VAT

Measuring performance of VAT

The gap between the standard VAT rate and the effective VAT rate4 is a crude measure of the VAT performance of a country. A large gap between the standard VAT rate and the effective VAT rate can be observed in Sri Lanka. In 2022, while the standard rate was 15%, the effective rate was only 1.6% (see Figure 2). The significant gap between the standard VAT rate and the effective VAT rate indicates that the VAT system is not collecting the revenue it theoretically has the potential to collect. The gap between the standard rate and the effective rate could be due to base erosion arising from a large number of exemptions, a high threshold, and a large number of transactions occurring in the informal economy. This gap could further increase when the tax administration fails to collect VAT revenue efficiently and effectively.

Issues in the VAT

1. Frequent changes to the VAT rate and threshold

The VAT rate in Sri Lanka has been changed eight times since the adoption of VAT in 2002. This is far in excess of other countries. For example New Zealand, one of the pioneers of VAT, has only changed the VAT rate twice since its adoption in 1986. The Philippines has only changed its standard rate once since its adoption in 1988, while Bangladesh has maintained the same rate since the adoption of VAT in 1991.

More recently, from 1 June 2022, the VAT rate was increased to 12% from 8% and subsequently raised again to 15% from 1 September 2022, indicating that policy changes in Sri Lanka are frequent and ad hoc and lack proper analysis.

Over the years, various rates have been applied to different categories of goods and services, including lower rates, luxury rates, standard rates, etc. Even though the rates were unified in 2004, it has been subjected to several ad hoc changes. These adjustments, often unforeseen, add complexity to the VAT system.

When considering a rate increase to raise revenue, it is essential to evaluate both the efficiency of VAT rates in revenue generation and the potential consequences involved. Increasing the VAT rate beyond an optimal level can adversely affect the purchasing power of individuals and consumption patterns. As VAT is a consumption tax, higher rates translate to increased prices for goods and services. This, in turn, reduces the disposable income of consumers, diminishing their purchasing power. Businesses may also experience reduced demand, affecting production and economic growth.

2. A large number of exemptions

Since the implementation of VAT in 2002, a large number of goods and services have been exempted from VAT due to lobbying by interested parties. These exemptions have been granted without clear economic rationale, resulting in a narrowing of the VAT base. The original VAT Act provided a list of exemptions covering a few selected areas such as unprocessed agricultural products, education and healthcare. But over the years, more items were added to the list of exemptions, systematically eroding the VAT base.

Granting exemptions to selected industries or sectors such as Information technology can disproportionately favour certain market segments and lead to picking winners. Moreover, VAT exemptions have also been granted under the Strategic Development Projects Act, No. 14 of 2008 (SDP Act), Board of Investments as well as under Colombo Port City Economic Commission Act, No. 11 of 2021. Under the SDP Act, the supply of goods and services for projects identified as strategically important as well as projects that the Minister of Finance identifies considering its economic benefit to the country are exempted from VAT5. Such vague criteria for extending exemptions distort markets and create perverse incentives. Exemptions also lead to cascading6 where exempted goods and economic activities that use these goods and services as inputs are subject to a tax on tax.

A good VAT system is characterised by few exemptions. For instance in New Zealand, only four areas such as financial services, sales of donated goods by nonprofit organisations, certain real estate transactions and the supply of precious metals are exempted from VAT/GST7. It’s essential for authorities to carefully consider the rationale behind exemptions, keeping them to a minimum to protect low-income individuals and maintain a fair and balanced tax system.

Therefore the planned reductions in VAT exemptions should not be a temporary strategy to achieve short term revenue targets that would be abolished once the economy stabilises. Rather, keeping exemptions to a minimum should be the long term strategy adopted to ensure VAT is a stable source of revenue for the country.

3. Changes to VAT threshold

The VAT threshold in Sri Lanka is one of the highest in Asia resulting in a large portion of the Sri Lankan economy being exempt from VAT. The threshold has been revised six times since the VAT was introduced in 2002. In 2019, the VAT threshold was raised by 2400% from Rs. 12 million to Rs. 300 million. This reduced the number of persons registered for VAT from 28,914 in 2019 to 8,152 in 2020 (Table 1). This adds to the compliance problem as it is difficult to keep up with the new changes.

Even with the Government’s intention to decrease the VAT threshold from Rs. 80 million to Rs. 60 million with effect from 2024, it will continue to remain high compared to other countries, resulting in a significant portion of the economy being exempt from VAT. There needs to be a clear rationale for determining the VAT Threshold. The threshold can be determined on the basis of collection costs and the revenue foregone. Exempting small businesses from VAT would be justified as the cost incurred by the tax administration may be greater than the revenue gained.

4. Weak tax administration

Complex filing and payment procedures, coupled with multiple registration requirements and weak audit programs, discourage compliance among potential VAT payers. A streamlined and efficient VAT administration system is crucial for improving tax compliance. At the same time, use of computer generated invoices by the businesses should be encouraged to support VAT collection. The budget speech 2024 highlights the importance of the registered persons using Point of Sales (POS) machines that automate invoicing and sales recording as a measure to improve tax administration.

Moreover, the frequent amendments to the Value Added Tax Act since its adoption in 2002 (16 amendments in total) pose a major obstacle, affecting revenue estimates and making it challenging for both administrators and taxpayers to adapt to continuous changes. Policy Inconsistency and frequent changes to tax rates, the threshold and exemptions has made compliance harder for businesses as well as made administering the tax more challenging.

5. VAT on financial services

Since 2003, financial services have been included into the VAT system. Most countries exclude financial services from VAT due to the sensitivity of the financial sector to costs, the important role financial services play in the economy and the difficulty in calculating value addition attributable to different types of financial services in a VAT system. In Sri Lanka, VAT is applied on the additive method of net profit plus wages, where deduction is not allowed for input taxes paid. Financial institutions tend to pass on the VAT to their borrowers leading to a higher cost of credit.

Fairness of tax distribution – optimising tax

Despite VAT being a significant source of income, its regressivity is a major concern. An analysis of tax incidence8 showed that the lower income brackets allocate a higher proportion of their expenditure to essential items, such as food, while the higher income category spend more of their income on durable goods, housing and transportation. Therefore, this regressive nature of VAT can be eliminated by granting exemptions on essential items while abolishing exemptions granted on items like fuel, housing, etc. that disproportionately benefit the rich.

Despite the potential of VAT, revenue collection continues to fall short of expectations. Ad hoc changes to the VAT regime suggest a short-term revenue focus rather than viewing VAT as a stable, long-term revenue source. The way forward would be to determine VAT rates, thresholds and exemptions based on scientific analysis and clear economic rationale. Applying VAT to most goods and services is ideal, while a well-defined threshold can effectively exempt small traders from the VAT making it less regressive.

Footnotes:

1(Gaspar, Jaramillo, and Wingender, 2016)

2 http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2023/8/377-2023_E.pdf

3 Value-Added Tax Continues to Expand, IMF Finance & Development, March 2022.

4 The effective tax rate (ETR) is estimated as VAT revenue as a proportion of VAT base. From 2002 to 2009, GDP is used as the base, while from 2010 to 2020, the sum of Gross Value Added (GVA) and imports of goods and services is used as the VAT base.

5 http://www.ird.gov.lk/en/publications/Circulars_Circulars/Implementation%20of%20VAT%20on%20Special%20Projects.pdf

6 Cascading effect is when there is a tax on tax levied on a product at every step of the sale. The tax is levied on a value that includes tax paid by the previous buyer, thus, making the end consumer pay “tax on already paid tax”.

7https://www.vatupdate.com/2021/08/13/vat-gst-rates-in-new-zealand/

8 The Tax Incidence analysis was primarily based on the Household Income and Expenditure Survey conducted in 2019, which was the last available survey. By categorising households into income brackets, the study analysed expenditure shares on various goods and services to estimate VAT payable and determine the percentage of income spent on taxes.

(Roshan Perera is a Senior Research Fellow at Advocata Institute. She can be contacted via [email protected]. Thashikala Mendis is a Data Analyst at Advocata Institute. She can be contacted via [email protected]. Janani Wanigaratne is a Research Consultant at Advocata Institute. She can be contacted via [email protected]. The opinions expressed are the authors’ own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute or anyone affiliated with the institute.)