Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Tuesday, 3 November 2020 00:25 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Amidst the severe disruptions triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important for economies to formulate and implement effective policies to mitigate the negative impacts induced by the crisis.

As noted by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the pandemic has intensified the need for fiscal policy actions at an unprecedented level. As such, governments must intervene to protect the well-being of people during this challenging period. The length and depth of global economic shocks can be shortened by prudent fiscal measures by governments, thereby providing a protective shield against the adverse effects on people’s lives.

Despite national-level policy responses, a sustained recovery cannot be assured unless coordinated action is pursued at the global level as well.

Given the fact that Sri Lanka is an aspiring upper-middle-income country (UMIC), this blog examines fiscal responses by affected countries including Sri Lanka, at different income levels – i.e. high-income countries (HICs), middle-income countries (MICs), and low-income countries (LICs) in line with multilateral financial institutions’ (MFIs) recommendations.

Mitigating the adverse impacts

Governments need to address different aspects of the economy at various levels, to prevent or limit a catastrophic economic collapse during disasters. An economy continues progressively with its activities only when the income flow of economic agents (households and businesses) is uninterrupted; a disruption to this flow results in the slowdown of economic activities. In such a scenario, government interventions are essential to minimise the adverse effects of this vicious cycle of events.

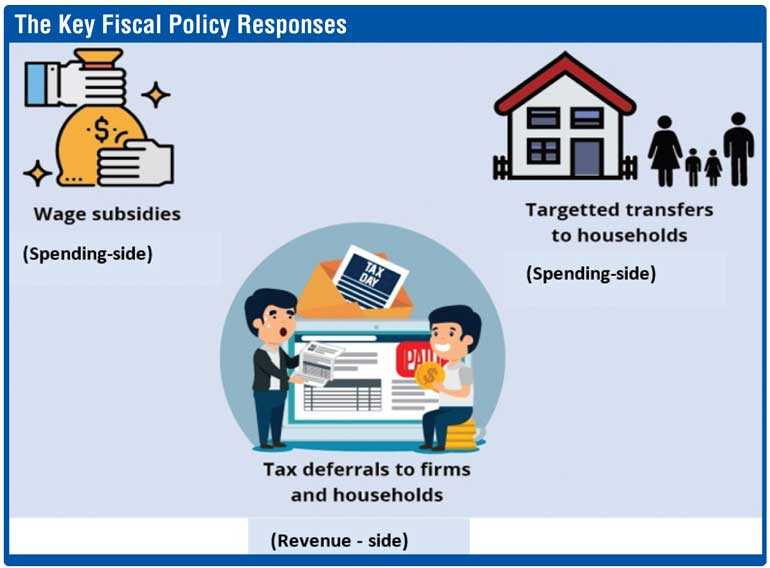

MFIs – the IMF and World Bank (WB) – recommend that governments follow specific fiscal measures to minimise the adverse effects arising from COVID-19. In a broader context, fiscal policy measures can be described as spending-side measures (immediate relief related spending on health and non-health sectors), revenue-side measures (tax deferrals, tax cuts, etc.), government-supported liquidity measures (cash flow support to businesses), and supplementary economic revival measures (relief to fast-track recovery).

In particular, revenue-side measures and government-supported liquidity measures can help reduce the severity of the impact, while economic revival measures can help boost growth in the medium and long-run. For instance, increased infrastructure expenditure can accelerate the revival of economic activities and create employment opportunities.

The global fiscal response

Globally, governments of COVID-19 affected countries have adopted various fiscal policy measures in line with the IMF/WB recommendations. However, each country’s policy responses vary depending on the income levels and its financial position.

More advanced countries collect more revenue as a share of their Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and spend more. Further, developed economies benefit from being able to borrow more without adverse risk factors. For example, advanced economies or HICs, emerging markets, and LICs have allocated on average 8.6, 2.8, and 1.4% of GDP as fiscal stimulus packages as responses to COVID-19, respectively.

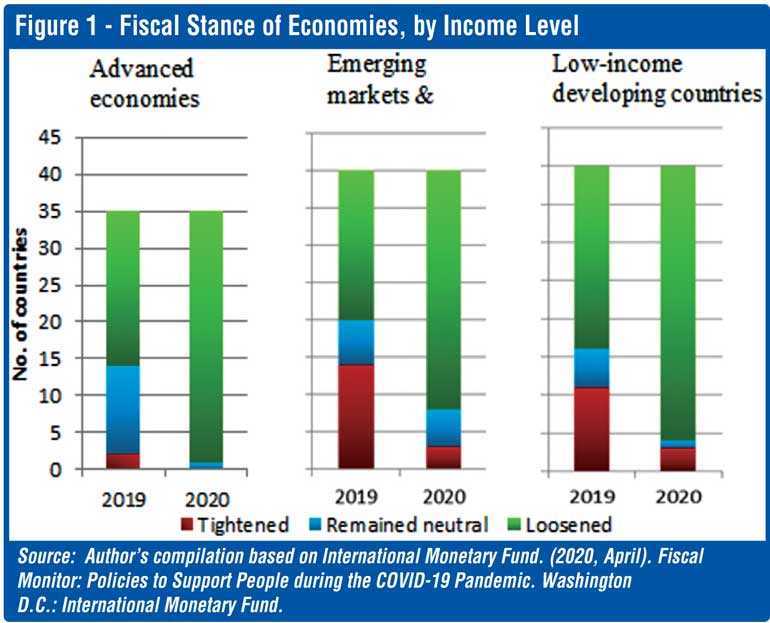

Countries in all income groups have adopted an expansionary fiscal policy (loose fiscal stances) to accompany the key measures, and thereby to counterbalance the disadvantageous effects of COVID-19 (see Figure 1).

Sri Lanka’s response and the way forward

Like other countries, Sri Lanka has also taken a range of measures to contain the spread of COVID-19, of which strengthening its health sector preparedness as well as adopting measures to minimise the economic fallout, have been priorities.

As of August 2020, the Government is estimated to have allocated 0.1% of GDP for containment measures and announced an additional allocation of nearly 0.25% of GDP for cash transfers for vulnerable groups, under its fiscal package.

In line with MFIs’ recommendations, policy responses are directed to spending and revenue-side measures (health and non-heath spending, extending payment deadlines for income tax, and tax exemptions on health imports), government-supported liquidity measures (debt moratoriums and working capital loans), and supplementary economic revival measures (loans for investments at concessional rates to businesses in IT, apparel, plantation, and tourism sectors).

However, the available fiscal space has limited the adequacy of allocations. In fact, Sri Lanka’s fiscal package is relatively small compared with other emerging and MICs in the Asian region such as Malaysia (17. 2% of GDP) and Thailand (11.4% of GDP).

The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to dampen growth substantially through reduced export earnings, private consumption, and investment in the short-run. In these circumstances, it is a challenge to adopt effective policy measures.

Countries with relatively weak initial conditions such as Sri Lanka must therefore ensure that resources are utilised efficiently, taking into account the time path and feasibility.

In addition to measures implemented so far, some complementary measures that can be considered are: (i) provision of financial assistance (government-supported liquidity measure) to start and continue e-commerce for industries such as healthcare, agriculture, and ICT, where new opportunities have emerged during the current pandemic; (ii) increasing infrastructure expenditure (supplementary economic revival measure) given large employment multiplier effects.

In view of Sri Lanka’s limited fiscal space, denoted by high fiscal deficits and public debt ratios, such programmes need to be well-focussed and followed up with pre- and post-implementation evaluation to ensure an optimum impact on the economy.

(This blog is based on IPS’ ‘Sri-Lanka: State of the Economy 2020’ report on ‘Pandemics and Disruptions: Reviving Sri Lanka’s Economy COVID-19 and Beyond’.)

(Chamini Thilanka is a Research Assistant at IPS. She holds a BA and a MA in Economics from the University of Peradeniya. She is a Visiting Lecturer at the Open University of Sri Lanka.)