Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Saturday, 27 April 2024 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

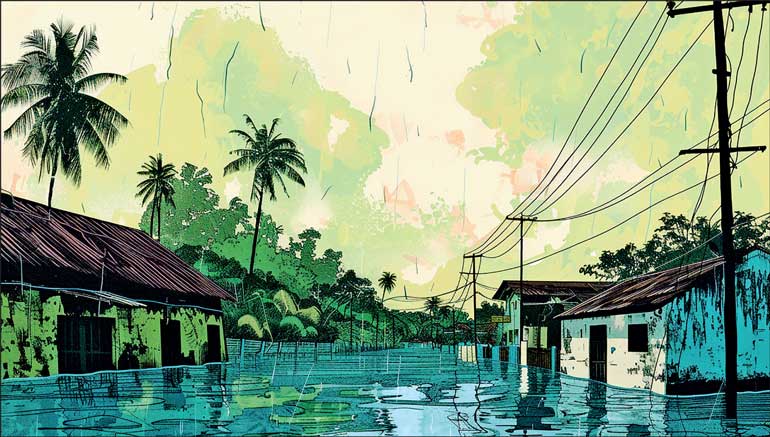

For climate finance and global funds, ensuring that funding reaches the local level and vulnerable

communities is a key challenge

Climate change impacts all sectors, administrative levels, and segments of society. Research has firmly established the need to mobilise significant resources for addressing these impacts, as well as the current gaps and shortfalls in this endeavour. According to the first Global Stocktake, which was finalised at the 28th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement (COP28) in December 2023, the adaptation finance needs of developing countries “are estimated at USD 215–387 billion annually up until 2030,” and their needs to implement their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) “at USD 5.8–5.9 trillion for the pre-2030 period.”

Climate change impacts all sectors, administrative levels, and segments of society. Research has firmly established the need to mobilise significant resources for addressing these impacts, as well as the current gaps and shortfalls in this endeavour. According to the first Global Stocktake, which was finalised at the 28th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement (COP28) in December 2023, the adaptation finance needs of developing countries “are estimated at USD 215–387 billion annually up until 2030,” and their needs to implement their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) “at USD 5.8–5.9 trillion for the pre-2030 period.”

Besides mobilising these funds—which will be a key topic for climate negotiations in 2024 and at COP29—, there is also a challenge in connecting the global to the national and local level. Ultimately, climate finance and other means of implementation—such as technology, technical support, and capacity-building—need to reach vulnerable communities and other local stakeholders at the frontlines of climate change, who depend on this support to reduce their vulnerabilities, adapt to climate impacts, and address climate-induced loss and damage.

Barriers and constraints for local-level access

The needs of communities, households, and vulnerable groups and individuals as outlined above are well established and documented. Global funds—such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the Adaptation Fund (AF), the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), and now the Loss and Damage Fund (L&DF)—have been created to address this urgent need for resources to scale up climate action and build resilience. However, local-level stakeholders are often unable to directly access these funds and have to rely on a chain of intermediary entities, which can lead to delays, transaction costs, and misalignment.

Key barriers and obstacles for local organisations, communities, and grassroots actors to access climate funding can include stringent eligibility criteria; complex application procedures and proposal templates; limited direct access modalities; lack of small grant windows; high fiduciary standards and reporting requirements; and the need for comprehensive scientific evidence and needs assessments.

In addition, another challenge for communities includes potential waiting periods and timelines for funding allocation, which can often span years and do not match the immediacy and urgency of ground-level needs in the face of climate action. Many local-level stakeholders are also not aware of available climate finance opportunities or lack a detailed understanding of how to access, manage, or report on such funds. Without this knowledge and empowerment, local stakeholders are left without the means to initiate and sustain relevant projects that address their specific needs and circumstances.

Local-level priorities and success metrics

Access to and the effective utilisation of funds also depends on clearly identified and communicable needs, priorities, and success metrics. How can resources at the local level be used to efficiently address climate impacts and risks in a targeted manner? How can the impact of such interventions be measured—especially when it comes to averted or addressed economic and non-economic damages and losses—without adding additional burdens on already vulnerable and resources-constrained communities? And how can it be ensured that the needs and voices of all groups are incorporated, including women, youth, the elderly, migrants, displaced persons, informal workers, or those with disabilities?

Setting up systems that can answer these questions is a key challenge that involves a range of different stakeholders on the local level—such as communities, grassroots organisations and associations, research institutions, civil society actors, and local authorities—as well as on the national and global level. In the context of the multilateral climate negotiations, workstreams such as those on the Global Goal on Adaptation and the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience, the Loss and Damage Fund, the technology work programme, or National Adaptation Plans and NDCs can connect to these ground realities and acknowledge them in the development of targets, indicators, modalities, guidelines, recommendations, reporting mechanisms, and guidance to global funds.

Conclusions

The challenge of local-level access to global funds is strongly connected to issues of climate justice and equity, but also to the need of ensuring the transparent and accountable disbursement and utilisation of funds, including robust monitoring, evaluation, reporting, and impact assessment mechanisms.

If local actors are to directly access funding, it is vital to build up and strengthen their relevant skills, competencies, and systems as well as their awareness of priorities, success metrics, and funding opportunities. Furthermore, other measures towards more equitable access to climate finance could include simplifying and streamlining application processes; enhancing direct access modalities and offering small grant windows; adapting flexible or scalable eligibility and disbursement criteria; involving local stakeholders directly in decision-making processes around funding allocation and enhance their participation, representation, and ownership of the process.

Addressing these challenges is important to ensure that climate finance is effective and equitable and contributes towards the adaptation and long-term resilience-building efforts of local actors in appropriate, inclusive, and context-specific ways. The path forward involves not just adjustments in the mechanisms of funding but a deeper recognition of local realities and needs in the global climate finance architecture and the wider financial system.

(The writer works as Director: Research and Knowledge Management at SLYCAN Trust, a non-profit think tank based in Sri Lanka. His work focuses on climate change, adaptation, resilience, ecosystem conservation, just transition, human mobility, and a range of related issues. He holds a Master’s degree in Education from the University of Cologne, Germany and is a regular contributor to several international and local

media outlets.)