Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Thursday, 20 February 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Readiness for the future brings education to the centre of the debate. The mantra is ‘learn to learn,’ not simply learn to pass examinations that test what has been learned – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

We are constantly told that the workplace or private spaces of the future will be radically changed due to rapid technological changes, but the only certainty about this future is its uncertainty. How do we face such an uncertain future? The consensus is that the best we can do is to be ready for change.

Readiness for the future brings education to the centre of the debate. The mantra is ‘learn to learn,’ not simply learn to pass examinations that test what has been learned. Education philosophers have been arguing for centuries for the same kind of learning but to no avail. Increasing massification of education has led to the mass production of credentialed individuals. The 21st century could well be the time when learning to learn as an objective of education becomes a reality.

Good schools are central to the readiness of a populace

Access to school education has improved considerably in the past few decades. Quality of education is now the major issue. Parallel to the rise in school attendance has been the growth in the demand for higher education. From an efficiency standpoint, there is ample evidence to show that the quality of school education is the real driver for economic growth (Wolf, 2012 and references therein).

Mass higher education is driven by socio-political imperatives

In contrast to school education, mass higher education has not shown any impact on economic growth according to studies spanning a cross-section of economies worldwide. South Korea is a case in point. Its investment in school education in the ’60s and ’70s is attributed to its economic growth. Growth in higher education has been a result of economic growth, not a driver.

Yet politicians continue to subsidise higher education for larger and larger portions of the youth population in response to the social demand for higher education. Education is a positional good. It is not what you have. It is what you have in comparison to what others have. This characteristic of education leads to an inflation of the value of credentials.

Decades ago, a school-leaving certificate was enough for ‘signalling’ one’s potential for most jobs. A degree was a rarity. Today with more and more people acquiring degrees, vocational education is for somebody else’s child. Every parent aspires for a degree qualification for their child.

Politicians understand and respond, sometimes with a mistaken notion that mass higher education is important for growth. In other situations, it is a socio-political imperative. For example, in Sri Lanka, the manifesto of Gotabaya Rajapaksa (GR) who was elected as President says: “I know every parent aspires for a degree for their child. Therefore, we will provide opportunities for every child who passes A/L.”

Elite higher education is still a necessity

The economic irrelevance mass higher education highlights the importance of elite higher education. A critical mass of high calibre graduates serves a pivotal role in driving any economy.

The clustering of intellectual power around Silicon Valley, for example, has clearly been a driver for the technological changes we are experiencing.

How does Sri Lanka fare?

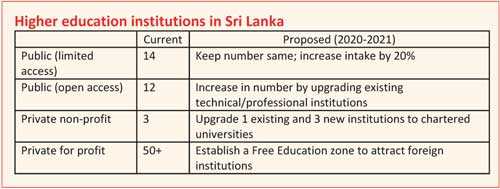

Higher education institutions in Sri Lanka can be broadly classified into four types of institutions: Public (limited access); public (open access); private (non-profit) and private (for profit). Limited access public institutions constitute the 14 public universities to which admission is closed except for those who gain a minimum Z-score or a standardised score at the GCE (A/L) examination.

Open access public institutions are those which manage their own admissions but charge a nominal fee. These have slowly emerged as a response to the demand for public sector backed higher education. Without an adequate philanthropist base, private non-profit institutions are a rarity in Sri Lanka. The Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology and the Aquinas Institute for Higher Education are two such entities set up as Limited liability private companies. The National School of Business Management is limited by shares company of the government, but it is committed to channelling profits for education ends.

In a 2012 survey of the higher education landscape in Sri Lanka, LIRNEasia uncovered 49 institutions awarding foreign degrees, but there were no branches of foreign universities in Sri Lanka. Today the number of private institutions is expected to exceed 50.

The present Government proposes to almost triple the intake through a 20% increase in enrolments to public universities, elevating the current degree awarding public institutions to chartered universities, elevating diploma awarding public institutions and professional associations to degree status, continuing the loans to students to attend private universities, and establishing a Free Education Zone for establishing branches of quality foreign universities.

This proposed total annual intake represents about 33% of school leavers in any given year. In the US presently, the university attendance is at 50% and completion rates are about 33%. Our aspirations are compatible with the USA, but not our capabilities. The obvious result of this rapid expansion will be a multitude of low-quality degree mills with a handful of winners. These winners will not necessarily be the established public universities.

Public universities should be vanguard institutions, but…

The 14 public universities represent a substantial investment of Treasury funds and World Bank loans. In contrast, most other higher education providers need to meet their loan obligations every month. Privileges come with responsibilities. Public universities have a responsibility to excel above others, but they fall short by leagues.

Public universities have a higher percentage of faculty with PHDs or full professorships, but the credentialing and promotion processes of these institutions are opaque.

There have been many self-congratulations about the University of Peradeniya moving up the ranks in the international Time Higher Education Ranking system in 2019, but few understand that it is due to a fluke in the way citations are counted. In order that public universities fulfil their obligation to be vanguard institutions, we need to look at performance measures that matter.

Predictable and productive academic calendars is a must

Politicisation and opportunism are the real issues that are not captured by global ranking systems or web-based metrics. Public universities are characterised by militant student factions, faculty who succumb to unreasonable demands of these factions, and politicians who pamper to both groups. Academic calendars have been manipulated over time so that students get to spend 30% or more of their time on study leave and examinations.

For a semester with 15 weeks of classes student demand and receive eight or more weeks for study leave and exams. This leaves large chunks of time for militant students to carry out their propaganda. Productive faculty find it difficult to find time for research. Student internships or exchange programs are impossible to organise. Unproductive faculty use the time for private gain.

In contrast, the National University of Malaysia, for example, allows a maximum of three weeks for examination for a semester with 15 weeks of classes and the academic calendar is consistent. In Sri Lanka, academic calendars change every year and they are not consistent across campuses or even across faculties within the same campus. A predictable and productive calendar is a necessary basic condition.

Mandated performance criteria

To really meet future challenges, public universities should go beyond necessities to self-monitoring for performance. Better still, the Ministry of Higher Education should mandate such performance measures.

Some of the basic performance indicators such as retention and graduation rates, age at graduation must be reported for all institutions such that data are comparable at a glance. Faculty quality indicators too are important.

Openness as the capstone

Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman; and publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases. In Sri Lanka, we have a Right to Information Act which mandates State institutions to make certain basic information available to the public. It is time to define key data for reporting by universities and ensure that such data are shared. Openness can be on three fronts.

The Ministry of Higher Education should develop a format for reporting performance measures. These measures should be available as a dashboard on the ministry web site comparing institutions in relation to each performance measure. The initiative should begin with public universities and extend to all other institutions.

The knowledge outputs of universities are graduates they produce, faculty who mature to become professors, and thesis and academic paper produced by these intellectuals. Openness in this context means that all outputs leading to a degree, for example, should be submitted to the National Library and posted online as a requirement for graduation. This is the practice in developed countries. In the USA, there is no one authority but Canada has a national online portal for university theses.

Promotions within the university too should be more open. Currently, they are tainted by stories of plagiarism and unsavoury practices. A simple method would be to make available the CVs of every faculty member in the public domain with links to their publications and other achievements.

Openness to innovation is really the key to the survival for public universities. Big league universities are already responding. The MicroMasters programs at MIT conducted in partnership with EdX is a case in point. Here you don’t need any prior credentials to complete requisite first semester courses for a set of designated master’s programs.

The courses are made available for free on www.edx.org. At any time, 100,000 to 300,000 students may follow the online courses. Those who pay and successfully complete proctored examinations on the requisite five courses will be awarded a MicroMaster’s credential from MIT. This credential gives the holder affiliate membership in the MIT alumni association. Further, the holder can apply for onsite master’s program at MIT with credits for semester one.

These kinds of innovations give flexibility to learners to bypass four-year degree programs and receive the education they need when they need it. Institutions get to tap into a vast global talent pool.

Our public universities need to start innovating in small steps. A research-intensive degree program where a few select students can engage in research from day one may be one such initiative. These students, for example, can be allowed self-study with the assistance of open online courses from world-class universities, and complete their degree requirements. They can graduate with a degree as well as research credentials. Vanguard national universities should really be about research-based teaching, not glorified tutoring.