Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Monday, 13 June 2022 00:15 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Rebel who is not quite quiet

Rebel who is not quite quiet

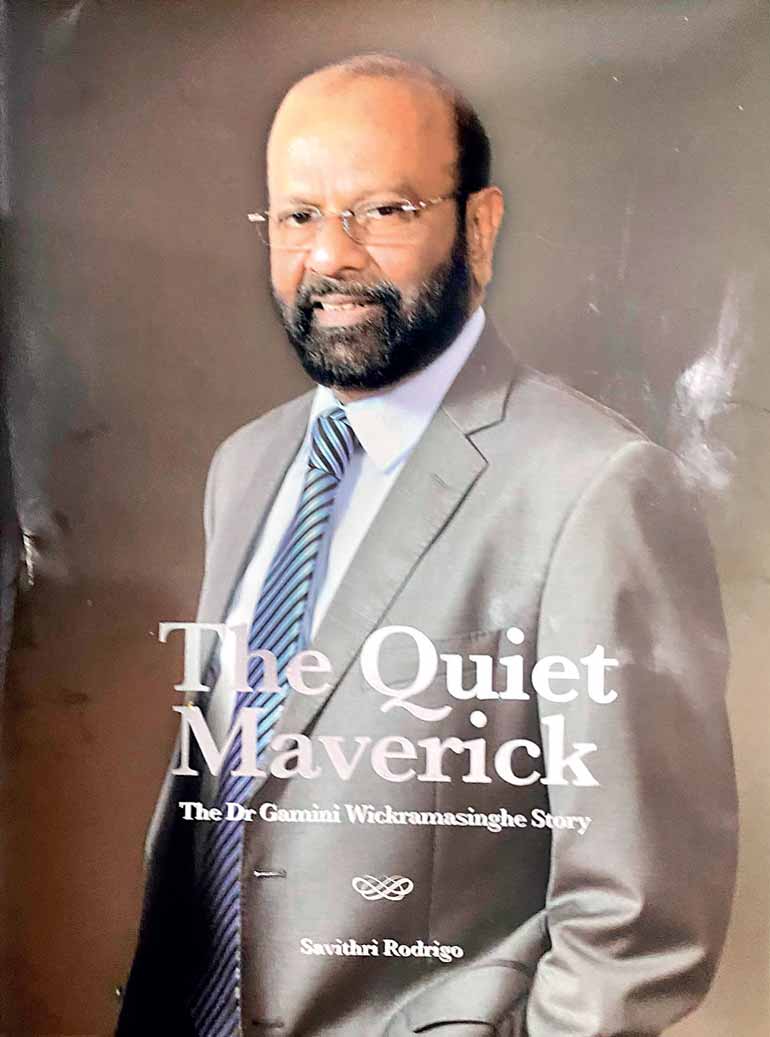

Can someone wear so many hats during his professional and personal life? Yes, if you are Gamini Wickramasinghe, says Savithri Rodrigo, biographer and TV presenter, in her latest, ‘The Quiet Maverick: The Dr Gamini Wickramasinghe Story’, released a few months ago. But when one goes through the story of this maverick, one will have to disagree with Savithri; that is, Gamini is not a quiet rebel at all. His track record marked by so many hats he has worn in his professional life – entrepreneur, trailblazer, regulator, banker, and educationist – is quite sounding and noisy. An apt appellation that I can think of about him is that he is an ‘unsung hero’ among us.

The easy-going traveller

I met Gamini when he was the Chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission and Insurance Board of Sri Lanka and later the Chair of Sri Lanka’s top bank, Bank of Ceylon, in early 2000s. We had fruitful discussions on economics, businesses, IT sector and many more. He was my constant source of info on global trends in ICT and innovative businesses.

He had visited many countries and he always had some learning takeaways from those countries. I still recall his story of Northern Australian cashew farmers growing tall trees around their expansive cashew farms. He said that the purpose was to permit an easy hanging place for nocturnal cashew-apple thieves – bats – to devour their spoils. In the morning, the farmers would collect the cashew seeds that have been scattered by bats under those trees.

His point was that if you are innovative, you can find solutions for even impossible issues. The normal approach would have been trying to eliminate those thieves by shooting them in the night, an environmental mess and elusive goal. In the case of Gamini, I recall that he tried to find those unconventional solutions to seemingly impossible ones.

The bookish ruggerite

The bookish ruggerite

Gamini has been born to an urban middle-class family, his father a post-master and mother a responsible housewife. His maternal and paternal relatives had belonged to rural aristocracy. He has been schooled at Ananda College, a prestigious college for boys in Colombo. He was a bookish boy driven to the world created by writers like Enid Blyton, a habit he had picked up from his eldest sister who was a teacher at the Royal College. But his burning passion for sports could not be extinguished by befriending books. As a youth, he chose to captain the Ananda’s rugby team which brought many honours to the College.

But it interfered with his studies which his parents had already chosen for him: medicine as the top priority or if it was not possible, engineering as the second best. When he found that either one was not his forte, he surprised his parents announcing that he wanted to go to England to study technology. This was typical of a maverick or a rebel by dismissing the socially accepted norm of the day. His parents reluctantly yielded for they knew that they will not be able to stop Gamini once he had made a choice. That was how Gamini landed in England in late 1960s with only £ 25 in his pocket, a risky enterprise by any standard.

The man who has gone through the mill

Gamini had not experienced the type of economic hardships as many other students had done during his childhood. His parents were ready to support him financially when the need had arisen. But when he landed in the UK with that meagre endowment on hand, despite the readiness of his elder brother who had settled down there earlier to support him, Gamini chose to seek his fortunes in that strange country alone. He moved to a separate accommodation that cost him £ 6 per month, found a job as a stock warehouse labourer, and commenced his studies in both accounting and computer science.

This was a new learning experience for Gamini, and it helped him to go through the mill that was instrumental in shaping his later personal and professional life. That learning firmly ingrained in him that he should stand on his own feet if he was to attain the cherished goals in his life. In that respect, relying on others will be purposeless. Later, he did other odd jobs like driving a forklift at a factory and a night watchman at a Yard. With prudent money handling, soon, he became the proud owner of a scooter to move about in London and later a motor car, accumulating assets one by one which a youngster usually aspire for. The scooter had cost him £ 10 and the motor car £ 50 in those days.

The star worker at Phillips Petroleum

The star worker at Phillips Petroleum

Gamini completed his technical education in the UK by doing a Master’s degree in Systems Analysis at the University of Aston, Birmingham, and later management education by doing a Doctorate in Business Administration at the Manchester Metropolitan University. Before completing his Master’s, he had started working with Rank Hovis McDougall, known as RHM, a food manufacturing company in England, as a programmer. Soon, he was elevated to analyst. The job involved travelling to other countries in which RHM had a presence. He used the opportunity to learn more on the job.

When RHM offered him sponsorship of the British citizenship which it does for star employees, he declined it guided by his nationalistic sentiments. But in hindsight, he now feels that he made a mistake. Then, he had a stint at the Phillips Petroleum, an American petroleum giant, in its Chemicals Division in England. All these offered an invaluable experience for a young Sri Lankan who chose to get educated outside the country. That had laid the foundation for Gamini to start his entrepreneurial career back at home.

Venturing into business

After returning to Sri Lanka having completed his vocational stint in England, Gamini began to test his entrepreneurial skills. The newly opened open economy system in early 1980s provided him with opportunities. His specialty was in IT, and he tried to seek his fortune in that area. Besides, Sri Lanka’s entry into the sector had been primitive and it was still an unexplored and unchartered business line. Computer giants like IBM, HP, and Honeywell had already put in firm footsteps in Sri Lanka’s fledgling IT sector. He wanted to go for a new brand of quality and reputation. His choice was Germany’s Number 2 brand, Nixdorf. While working with Phillips Petroleum he had some contacts with Nixdorf. He used this contact to invite Nixdorf to Sri Lanka.

Choosing a name

Choosing a name

Choosing a name for a new company is the most difficult task. Sometimes it comes automatically by accident as was the case with Apple. In this case, an apple of which a bite had been eaten had been lying on the table of Steve Jobs when he was pressed for making that choice according to his biographer, Walter Isaacson. Noticing this, Jobs had chosen Apple as the name of the company and a bite-eaten apple as its logo. This has served well for Apple for five decades now without the need for rebranding.

When choosing a name for a company, the practice of many entrepreneurs in Sri Lanka had been to consult astrologers and sound-experts to propose a suitable name to ward off malefic effects that might befall the company’s business later. But Gamini, the rebel, did the unconventional. He searched for a suitable name by perusing tech-related publications and zeroed on Informatics. Later, he had confessed ‘It was just one word, rolled off the tongue, and basically gave the technology idea’.

So, Informatics was chosen, and it offered IT services, especially systems developments, to Sri Lankan agencies. Later, he decided to move into IT education, and that was how the Informatics Institute of Technology or IIT was born. The acronym IIT has a connotation to the famous Indian Institutes of Technology, the producer of IT experts to the world.

Pioneer in IT industry

So, Gamini was one of the pioneers in the IT industry in Sri Lanka. Upali Wijewardena, the then Chair of the foreign investment promotion agency in the country, Greater Colombo Economic Commission, tried to do this with foreign investments but failed. Gamini did it on his own without the support of the governmental authorities. Today, IT is viewed as the saviour of Sri Lanka in its journey toward the Fourth Industrial Revolution or Industry 4.0. To attain that goal, as the Austrian American economist Joseph Schumpeter had said in 1942, thousands of such innovative businesses should spring up following the footsteps of Informatics, the original innovator. It involves two more steps: dissemination of original innovation and then, imitation of same by other entrepreneurs.

Moving to education

Over years, IIT became a leading higher education institute in Sri Lanka. It was started very small with only 22 students in the first year but soon grew bigger. Gamini was supported in this venture by Lalith Athulathmudali, the then Minister of Higher Education and his relative, by getting Cabinet approval for local institutions to offer quality degrees of British universities. He was first affiliated to Keele University and later to the University of Westminster. Year after year, student numbers swelled making IIT one of the most demanded higher learning institutions in Sri Lanka. Students could do the entire degree in Sri Lanka thereby saving personal investment as well as foreign exchange outflows.

There were annual graduation ceremonies well-attended by Vice Chancellors and senior academics of affiliated universities. I had the opportunity of attending such a ceremony held at BMICH in 2018. It was glamorous, colourful, and well-organised. One extraordinary beauty that I noted in the ceremony was the distribution of a book presenting the current profiles of the alumni of IIT. That book will help the current and past students to get connected to each other thereby enabling them to build what is known as ‘professional capital’ – networks of professionals that could be tapped whenever the need arises. I recall that there were thousands of such profiles in the book.

Regulator of the stock market and the insurance industry

Regulator of the stock market and the insurance industry

Gamini’s stint as regulator and banker in early 2000s was a different experience for him. He was to regulate both the stock market and the insurance industry. This was not something which he had bargained for. He says that he got a phone call from somebody that he had been appointed as the Chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission or SEC. He has confessed to Savithri: “This came out of the blue. Nobody asked me if I wanted it. I do believe I was just appointed.” He had not known anything about SEC and therefore, had delayed his decision. Later, he had decided that it would help him to broaden his horizons.

Since the Insurance Board at that time had been bundled with SEC, it came as a joint product. So, Gamini became the Chair of both. The rebel once again assumed office without fanfare, without family members present by his side, and without religious ceremonies. The success of business, he firmly believed, will depend on his applying business strategies and not powers given to him by supernatural powers. I recall that at both SEC and Insurance Board, he took special measures to improve the IT infrastructure and popularise education of would-be investors, two areas which needed special attention and in which he was a specialist.

Stint at the Bank of Ceylon

His migration to Bank of Ceylon as its chair was also a similar surprise. Nobody had asked Gamini whether he liked to be the Chair of that leading bank. He got the communication that he had been appointed to the post. He thus became a banker overnight finding himself walking into its main premises in Fort on one morning in 2007 amidst many waiting to receive him.

He has confessed to Savithri his biggest worry and the challenge at the Bank: “The asset base at the time would have been Rs. 237 billion and profits was Rs. 1 billion. Service levels weren’t exactly stellar because being a customer of the bank myself, I knew that an attitudinal change was vital. BOC had never attracted the private sector because of the typical public sector attitude and there were private banks that had taken over a place that would have rightfully been ours.”

That was his challenge at BOC, and he soon prepared a plan to rectify the deficiencies. At the time he left it, BOC had an asset base of Rs. 1 trillion and made annual profits amounting to Rs. 10 billion.

Secret of success

What is the secret of Gamini’s success as an entrepreneur? He is an unassuming, down to earth simple person who is willing to listen to anyone if that person had something to teach him. He moved with politicians of all hues. Above all, he was proactive and knew exactly what will happen tomorrow. When you know it, you can make yourself ready for it.

Savithri, biographer par excellence

Savithri has done a wonderful job in narrating the story of this rebel whose activities have not been quiet but sounding enough for all of us to see. She has proved once again that she is a biographer par excellence. Her lucid writing style will compel readers to finish reading it at a stretch.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)