Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Monday, 8 February 2021 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Call for a positive mindset

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, fondly called Gota, in his address to the nation at the 73rd anniversary celebration of independence made a very important appeal. He appealed to Sri Lankans to develop a positive mindset shedding the negative one being harboured by many across a wide spectrum of society. His appeal is timely because he wants to resuscitate the failing economy which he had inherited and worsened by the unexpected attack of the COVID-19 pandemic.

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, fondly called Gota, in his address to the nation at the 73rd anniversary celebration of independence made a very important appeal. He appealed to Sri Lankans to develop a positive mindset shedding the negative one being harboured by many across a wide spectrum of society. His appeal is timely because he wants to resuscitate the failing economy which he had inherited and worsened by the unexpected attack of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Only four more years are left in his current term and unless he acts in double-quick time, his expectation of delivering prosperity to Sri Lankans will evaporate into the thin air. Hence, as the powerful Executive President, solidified by the 20th Amendment to the Constitution, he had a good reason to make this appeal. But it appears that there is much more to be done for realising his goal than getting people to have a mere positive mindset.

It is good ideas that have ushered prosperity

It is well-known that countries which have succeeded in becoming rich nations have done so not because they had been endowed with natural resources or centralised tough leadership at the top but because people at large were having productive ideas which Gota had termed as positive mindsets. This has been the main theme of the book published in 2012 by economists, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, titled ‘Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty’.

But Acemoglu and Robinson Thesis which we can abbreviate as ART for easy reference is much wider than what Gota had meant by positive mindsets. It is therefore useful to elaborate the conditions under which Gota’s appeal will work when delivering prosperity which he promised in his election manifesto, represented in the Vista for Prosperity Program and cogently pronounced in his Independence Day address.

Acemoglu-Robinson Thesis

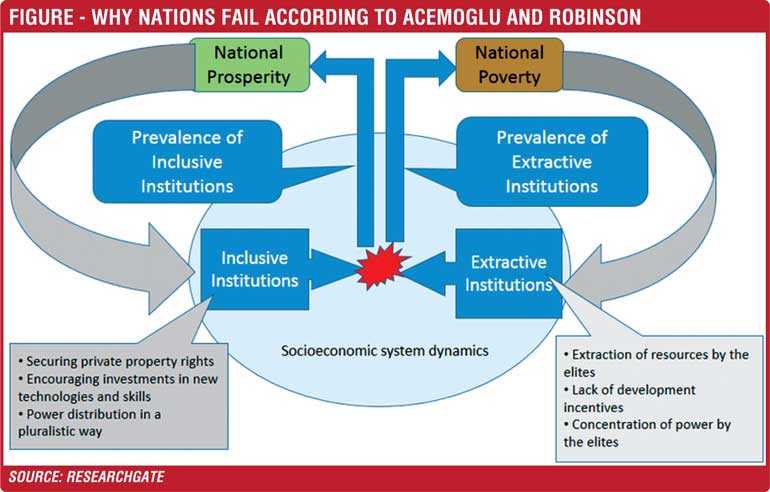

ART has refuted the popular theories relating to the differences in prosperity among nations. The leading such theories have been the geographical disadvantage, cultural disability, or ignorance of policy makers of the suitable policies for a country. Instead, they emphasise on one important requirement for a nation to break the fetters to which it had been tied. That requirement is the existence and promotion of inclusive economic and political institutions in the system.

Institutions in economics are not the formal organisations or bodies as is popularly believed. They are, according to ART, ‘rules influencing how the economy works, and the incentives that motivate people’. In a more elaborative sense, this could be translated into ‘values, beliefs, and ethos of a people’ in society. Thus, what Gota has termed as positive mindsets is the presence of ‘positive values, positive beliefs, or positive ethos’. These will cause a nation to prosper, gain power and eliminate poverty, three Ps of attainments by a nation and the subtitle of the Acemoglu and Robinson Book. By the same token, it can be concluded that the presence of ‘negative values, negative beliefs, or negative ethos’ is costly for a nation in its attempt at delivering prosperity to people. Yet, there are other conditions which should be satisfied for delivering this goal to a nation.

Four pillars of success of a nation

According to ART, there are four pillars that contribute to the success of a nation.

One is the assurance of property rights; the right exercised by people when using their physical property and human capacity without the fear of being robbed by another. It does not matter whether the robbing is being done by the government or by the private sector. To be successful, the possibility for such robbing should be eliminated at all costs.

The second is the political rights of people which should be very widely distributed among the whole citizenry irrespective of creed, ethnicity, or language. If the political power has been concentrated in one person or a few, ART says that it is inimical to progress because those in power will pass laws and make rules to enable them to remain in power and not for the general benefit of the people. This is evident from the experiences in Sri Lanka when a particular political party had got extraordinary power in Parliament in 1970s, 1980s and today.

make rules to enable them to remain in power and not for the general benefit of the people. This is evident from the experiences in Sri Lanka when a particular political party had got extraordinary power in Parliament in 1970s, 1980s and today.

The third pillar is the existence of a government which is accountable for its action, both progressive and regressive. The best position which a nation can reach in this regard happens when the government in power takes responsibility for its failures voluntarily. If it does not, there should be systems in which the government is forced to do so. It is in societies in which the power has been distributed properly among the three bodies – the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary – that such accountability can be ensured. Accountability will be missing in societies in which power has been concentrated in one or a group of individuals.

The final pillar is the existence of a sufficiently strong central government to observe the rule of law, ensure law and order and adjudicate justice fairly. Such strong governments will fight instances of the abuse of law and order more effectively than weak governments.

When these pillars are absent, it is unlikely that constructive ideas alone could effectively deliver prosperity to a nation.

Robbing is justified by extractive institutions

Institutions – values, beliefs, and ethos of a people – can be either extractive or inclusive.

When people harbour extractive values, beliefs, or ethos, robbing others or taking advantage of their weaknesses is fully justified. The recently popularised Dhammika Syrup as a medication for COVID-19 and believed to have been concocted by using a formula revealed by the mythological Hindu Goddess Kaali, is a case in point. This can happen at family, village, region, or national levels. And it can be practiced by all – those in politics, religion, civil society movements, or private business.

If a person or a group of persons wants to live by robbing others, there is a prime prerequisite that must be satisfied. There should be other people who create wealth so that those who believe in robbing could extract their wealth for them. But when they feel that their wealth is being robbed by others lawfully or unlawfully, they do not have incentive to create further wealth. Hence, ART says that under an extractive institutional setup, there is economic stagnation and wide-spread poverty.

Extractive institutions impede technological progress

Highlighting that economies generate prosperity by creatively destroying the old, outdated habits and introducing new technologies, Acemoglu and Robinson have put this cogently as follows: “When both political and economic institutions are extractive, the incentives will not be there for creative destruction and technological change. For a while, the state may be able to create rapid economic growth by allocating resources and people by fiat, but this process is intrinsically limited. When the limits are hit, growth stops, as it did in the Soviet Union in the 1970s. Even when the Soviets achieved rapid economic growth, there was little technological change in most of the economy, though by pouring massive resources into the military they were able to develop military technologies and even pull ahead of the United States in the space and nuclear race for a short while. But this growth without creative destruction and without broad-based technological innovation was not sustainable and came to an abrupt end”.

Extractive institutions also fail due to infighting

But there are occasions where extractive institutions could generate an initial economic growth. ART says that such economic growth is limited, fragile, and inclined to fail. There are two reasons for this. One is that there could be infighting for wealth and power within the elite group which enjoys political or economic power presently. The absence of collaborative team spirit among the players in the elite group leads to the destruction of the economic system from within, a process known as economic implosion.

The other reason is more obvious. Those who are outside the elite group, having seen how wealth is being appropriated by the elitists, start outmanoeuvring and overwhelming them. The result is the change of power from one elitist group to another elitist group via revolutions, military coups or simply through democratic election systems. The new group start enjoying power and wealth ignoring the need for developing the economy.

Say Acemoglu and Robinson: “One implication of this is that even if a society under extractive institutions initially achieves some degree of state centralisation, it will not last. In fact, the infighting to take control of extractive institutions often leads to civil wars and widespread lawlessness, enshrining a persistent absence of state centralisation as in many nations in sub- Saharan Africa and some in Latin America and South Asia”. Thus, extractive institutions become unstable and so does the economy. Sri Lanka’s limping economy in the past 73 years is an example.

The need for inclusive institutions

Therefore, what is to be developed, according to ART, are inclusive institutions. The main feature of an inclusive institutional setup is that people harbour the value, belief, and ethos in them that political power should be broadly distributed among all and arbitrary action by political leaders should be capped. ART further elaborates on this point as follows: “Such political institutions also make it harder for others to usurp power and undermine the foundations of inclusive institutions. Those controlling political power cannot easily use it to set up extractive economic institutions for their own benefit. Inclusive economic institutions, in turn, create a more equitable distribution of resources, facilitating the persistence of inclusive political institutions”.

The defeat of the coup attempts by President Donald Trump after he was defeated in the Presidential Elections in USA in November 2020 by the bold stand of the US Judiciary and the legislature – the Senate and the Congress – is a testimony for this. That was possible because those who protected the American democracy were harbouring not merely the positive mindsets but inclusive values, beliefs, and ethos. And the opposite had been demonstrated after the Parliamentary elections in Myanmar. When the political movement led by State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi had a landslide victory at the election, the military devoid of inclusive values, beliefs, and ethos had taken control of power apparently in fear that it would lose its extractive rights.

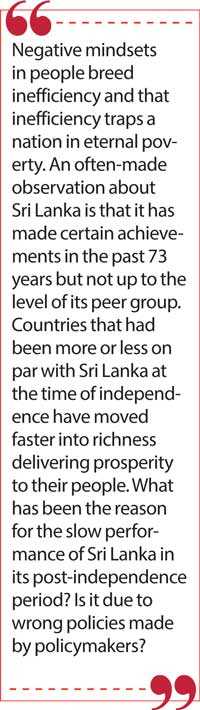

Negative mindsets breed inefficiency

Negative mindsets in people breed inefficiency and that inefficiency traps a nation in eternal poverty. An often-made observation about Sri Lanka is that it has made certain achievements in the past 73 years but not up to the level of its peer group. Countries that had been more or less on par with Sri Lanka at the time of independence have moved faster into richness delivering prosperity to their people. What has been the reason for the slow performance of Sri Lanka in its post-independence period? Is it due to wrong policies made by policymakers?

ART has the following answer to these questions in general: “Most economists and policymakers have focused on ‘getting it right,’ while what is really needed is an explanation for why poor nations ‘get it wrong.’ Getting it wrong is mostly not about ignorance or culture. As we will show, poor countries are poor because those who have power make choices that create poverty. They get it wrong not by mistake or ignorance but on purpose.

To understand this, you have to go beyond economics and expert advice on the best thing to do and, instead, study how decisions actually get made, who gets to make them, and why those people decide to do what they do. This is the study of politics and political processes. Traditionally economics has ignored politics, but understanding politics is crucial for explaining world inequality”. This observation applies to inequality within a country too.

Sri Lanka’s unequal income distribution

So, when economics is overwhelmed by political expedience, policymakers make choices that serve the politicians which in turn causes poverty to settle in a country permanently. Despite the pro-poor policies adopted by successive governments since independence, Sri Lanka’s inequitable income distribution has been the same. In 1953, the top 20% in society amassed 57% of the total income, while the lowest 20% got only 5%. In 2016, the two ratios are 51% and 5%, respectively, indicating that the rich have enriched the middle-class by passing a very small part of their income to the middle class, while keeping the poor in the same position. Accordingly, the Gini Coefficient, a popular measure of income inequality, had remained unchanged at 0.5 in 1953 as well as in 2016.

Combine positive mindset with inclusive institutions

Thus, a positive mindset in people will certainly help Sri Lanka in its journey toward prosperity. However, that alone is not sufficient. Sri Lanka should build and nurse an inclusive institutional setup in which all people irrespective of creed, ethnicity, or language could participate in the growth process and eventually share its benefits. This is Gota’s biggest challenge today. If he fails in resolving it, his remaining years too would not be different from what Sri Lanka had in the past 73 years.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)