Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Thursday, 9 September 2021 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Certainly, domestic remedies “have not been exhausted”, when a domestic accountability mechanism and process have not been initiated as indicated by President Mahinda Rajapaksa to the UNS-G on 21 May 2009, and recommended by the LLRC he appointed in 2011

There is no guarantee that the Gotabaya Rajapaksa presidency will not annually add-on yet another Commission to investigate the preceding Commissions including the most recently appointed and currently functioning one

The UNHRC resolution that 2015 Prime Minister Wickremesinghe authored and co-sponsored greatly exceeded the level of political and electoral tolerance of the overwhelming majority of the citizen-voters in Sri Lanka a

Even President Maithripala Sirisena speaking to the New York Times on the side-lines of the UN General Assembly in August 2015, and on his way back, to the BBC’s Sandeshaya, was strident in his disagreement with the reference to ‘foreign judges’

|

‘What is to be done’ and undone by the (returning) Foreign Minister, Prof. G.L. Peiris, to succeed in Geneva? Sri Lanka needn’t be a Cambodia, Myanmar, or even another Pakistan, or make up China’s undeclared Asian ‘Quad’

|

‘Militarisation’ can be tracked and traced by the number of military or ex-military brass in positions hitherto occupied by civilian administrators, and the roles, subjects and functions aberrantly assigned to the military or ex-military.

The Government’s lame riposte is that once retired, a military officer is a civilian, so their appointments, however ubiquitous, do not constitute a symptom of militarisation. Really?

With militarisation comes ‘militarism,’ a state of mind, turned into an ideology. There were large photographs posted on LankacNews, a website long-affiliated with leading personalities of the ruling coalition, of a large birthday-cake celebrating the 60th birthday of a high-ranking official. The cake had, among other decorations, AK-47s and grenades made of icing. On one side the cake bore the legend in English: “Greatest Son of Mother Sri Lanka”. It wasn’t the birthday of Mahinda Rajapaksa or Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

GL’s Geneva game

The note to the international community on ‘progress made’, by the Government of Sri Lanka, (GoSL) issued by the Foreign Ministry and dated 27 August 2021, says that it’s objection to the March 2021 UNHRC resolution was that it was without the consent of the country concerned and “adopted by a divided vote” (p 2, point 6).

Does anyone know of any vote anywhere, except in a totalitarian system which enforces conformity to the point of unanimity, that doesn’t involve a “division” and isn’t a “divided vote”? This week in parliament this Government obtained approval for two sets of controversial regulations, by “a divided vote”? Due to a lack of ideological masking and failure to maintain proper distance from the source, is the infection of totalitarian thinking spreading in the Government’s ranks like an ideological COVID-19?

Does anyone know of any vote anywhere, except in a totalitarian system which enforces conformity to the point of unanimity, that doesn’t involve a “division” and isn’t a “divided vote”? This week in parliament this Government obtained approval for two sets of controversial regulations, by “a divided vote”? Due to a lack of ideological masking and failure to maintain proper distance from the source, is the infection of totalitarian thinking spreading in the Government’s ranks like an ideological COVID-19?

The Government’s note says that “Sri Lanka rejects the establishment of an external evidence gathering mechanism when domestic remedies have not been exhausted and processes are ongoing”. (ibid)

Certainly, domestic remedies “have not been exhausted”, when a domestic accountability mechanism and process have not been initiated as indicated by President Mahinda Rajapaksa to the UNS-G on 21 May 2009, and recommended by the LLRC he appointed in 2011. A “process” is certainly “ongoing”, but that seems a reverse process: the Presidential release of those convicted of murder by the courts.

The most surreal note is struck by the Government’s assertion that it is willing to implement the recommendations of the Commission of Inquiry to Investigate and Inquire into the Findings and Recommendations of the Preceding Commissions and Committees. (p 9, points 13, 14)

Having zanily appointed a Commission of Inquiry to investigate the recommendations of earlier Commissions of Inquiry to Investigate—Commissions appointed by President Mahinda Rajapaksa—the latest Commission will present its final report in January 2022. There is no guarantee that the Gotabaya Rajapaksa presidency will not annually add-on yet another such Commission to investigate the preceding Commissions including the most recently appointed and currently functioning one.

None of this will convince in Geneva. Lacking logic itself, the Government’s counterarguments lack credibility.

Geneva gaps

Geneva gaps

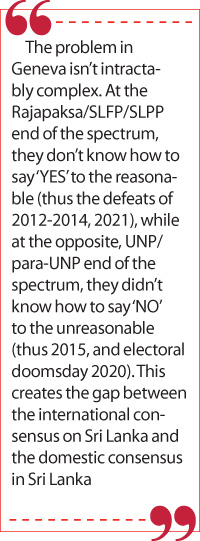

The problem in Geneva isn’t intractably complex. At the Rajapaksa/SLFP/SLPP end of the spectrum, they don’t know how to say ‘YES’ to the reasonable (thus the defeats of 2012-2014, 2021), while at the opposite, UNP/para-UNP end of the spectrum, they didn’t know how to say ‘NO’ to the unreasonable (thus 2015, and electoral doomsday 2020).

This creates the gap between the international consensus on Sri Lanka and the domestic consensus in Sri Lanka.

The minimum that the international community—as proportionately represented at the UNHRC—requires from Sri Lanka is greater than the maximum that the Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration is willing to concede.

The maximum (the TNA would say the minimum) that the UNP’s Geneva 2015 resolution was willing to concede on accountability, went and still goes beyond the maximum the national electorate is willing to tolerate.

The neoconservative Rajapaksa administrations are unable to convince a representative global audience; the neoliberal UNP administration was unable to convince a representative national audience.

The inability of the antipodal administrations to correctly balance the international and national compulsions lies at the heart of the Geneva crisis.

In Mahinda Rajapaksa’s first term, the gap between what was acceptable externally and internally, had been bridged in Geneva (2009).

Rajiva Wijesinha’s recent book records Mohan Peiris’ disclosure that the implementation of the recommendations of the LLRC chaired by former Attorney-General CR de Silva and appointed by President Mahinda Rajapaksa, was blocked by then Secretary/Defence Gotabaya Rajapaksa. (Chapter 7, p 108)

By blocking at the time, a reasonable recommendation containing the distilled legal and international experience of credentialed veterans of the upper echelon of the Sri Lankan state who had served through the long war (they urged an independent domestic probe into specifically listed cases), the Defence establishment now faces the prospect of an international inquiry and the invocation of universal jurisdiction in courts throughout the world, which will act on the material being prepared by the special mechanism set up in the Office of the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) pursuant to a resolution this March which saw Sri Lanka obtaining its lowest ever vote at the UNHRC.

The greater the influence and the veto power of the hawks, the greater the credibility gap between the Government and the international community. The international consensus recomposed in a manner greatly unfavourable to Sri Lanka as evidenced in the quadruple defeats 2012, 2013, 2014 and 2021.

UNHRC 2015, UNP at 75

UNHRC 2015, UNP at 75

No government had a better chance to resolve the problem that Sri Lanka faced in Geneva, than the Yahapalanaya administration of 2015, but the UNHRC resolution Prime Minister Wickremesinghe authored and co-sponsored, greatly exceeded the level of political and electoral tolerance of the overwhelming majority of the citizen-voters in Sri Lanka.

Even President Sirisena speaking to the New York Times on the side-lines of the UN General Assembly in August 2015, and on his way back, to the BBC’s Sandeshaya, was strident in his disagreement with the reference to ‘foreign judges’ and expressed his determination not to permit any foreign participation apart from the technical/forensic, in an accountability mechanism.

With the Foreign Affairs portfolio in UNP hands and the Geneva issue handled by Prime Minister Wickremesinghe, what were the options he had, but chose not to exercise?

1. Strengthening the independence of the Judiciary and leveraging that independence in Geneva to sincerely, credibly pledge a process of accountability through a purely domestic mechanism; leveraging the goodwill of the West to buy time and space for such a purely national inquiry.

2. The full implementation of the 13th Amendment. This was all that the Government of India had asked of us and that the Mahinda Rajapaksa administration had promised. The full implementation of the 13th Amendment is the only reference to devolution in any of the UNHRC resolutions to date. The only thing needed for the full implementation is the enactment of the requisite statutes. Given that ‘full implementation’ does not mean ‘instant implementation,’ the more contentious issue of Police powers could have been implemented in a phased manner.

3. Given the utterly polarising nature of the issue of wartime accountability, the UNP/Yahapalanaya Government could have pledged the time-bound implementation of the accountability recommendations of the blue-ribbon panels appointed by President Mahinda Rajapaksa, namely the LLRC, Udalagama and Paranagama Commissions, which would have pre-empted and precluded the inevitable onslaught by the MR-led Opposition of 2015-2019.

4. The 2015 Yahapalanaya Government had a full-fledged domestic option or national mechanism for accountability, prepared and presented in two detailed versions by the Attorney-General’s Department to the inter-agency roundtable convened by the Foreign Ministry in 2015. The Foreign Ministry ignored the AG’s Dept. proposals and shut down the inter-agency process. Knowledge of this contributed to the rift between President Sirisena and Prime Minister Wickremesinghe.

5. The UNP Government should have brought in Field Marshal Sarath Fonseka into the Foreign Ministry-led inter-agency process to scrutinise, edit and draw the parameters of the draft of the accountability mechanism in resolution 30/1. He could’ve drawn redlines which would have enabled him to pitch it to the military and get it on board.

The vast majority of citizens viewed Resolution 30/1 an effort to sit in judgement of the military, and worse, to induct or permit foreigners to do so, by a PM who had a reputation for appeasement of the LTTE, and lacked the national legitimacy of any role of wartime political leadership against the separatist-terrorist enemy.

On the 75th anniversary of the UNP, the reality is that almost 75% of the Sinhalese who are almost 75% of the country’s populace, turned against it. Yet, Ranil remains the leader.

In 1987-’88, the xenophobic nationalist wave against the Indo-Lanka accord and the IPKF presence was so ferocious that the UNP could hardly conduct an election campaign and was on the verge of being drowned in a bloodbath. It was rescued, as were democracy and the market economy, by the patriotic UNP candidate Premadasa who had pledged, just as his opponent Mrs. Bandaranaike had done, to remove the IPKF.

Prime Minister Wickremesinghe’s lopsided, Norway-facilitated Ceasefire Agreement (CFA) with the LTTE led to his ouster by President Chandrika Kumaratunga in late 2003 and his defeat by an unsympathetic electorate at the Parliamentary Election in 2004. A Tamil boycott sealed Ranil’s defeat at the Presidential Election of 2005 while a Sinhala shift insulated Mahinda from its effect and won him the presidency.

Despite this enormous evidence of lived experience, the UNP elite in 2015 was not prepared for any Geneva option that did not commit to “foreign judges, prosecutors, investigators,” etc. It gave the TNA a veto over the stand taken by the Sri Lankan state in Geneva. The excuse was/is that the victims will accept nothing less and nor will the international community, by which they meant/mean those Western countries with Tamil diaspora voters (as distinct from 80 million Tamil voters—India was not a co-sponsor).

Contrary to the 2015 UNP perspective, no government in the Geneva arena can, should or does view matters as an INGO or NGO would. It must view issues through the prism of the enlightened interest of the state; the republic and its citizens taken as a totality, a whole.

Ranil and his like-minded colleagues believed that the only way to earn international credibility was not by an independent, fully national judicial mechanism and process but by means of international presence and participation in an accountability mechanism. This was not comparable with the inquiry headed by a retired Commonwealth judges into the landmine which blew up Generals Kobbekaduwa and Wimalaratne. This was a full-on judicial process, including foreign judges, investigators and prosecutors, literally holding court in Sri Lanka on a 30-years war that the sovereign, democratic Sri Lankan state had won.

Where could such a warped, self-destructive policy arise from? I find no explanation more incisive and deeper-going than the following passage:

“This is a slavish mentality. There is no belief in one’s own capabilities. There is no belief in self-help. One lives in a way that somebody else wants. A long time has elapsed since Independence, but the slavish mentality, this mental and psychological laziness is still with a large number of us.” (‘Time for Action’ by R. Premadasa, Selected Speeches 1979-1980, compiled by Christy Cooray, Colombo 1980, reproduced in the Ranasinghe Premadasa Felicitation Volume: A Prime Minister with a Vision, 1985, p 65).

What Premadasa posited as Prime Minister, he practiced as President. When UK High Commissioner David Gladstone crossed the line between election observer and intervener, (entering a local Police station to file a complaint) he was declared persona non grata.

Under Ranil Wickremesinghe’s leadership, the UNP became the agency for the attitude and headquarters and home for the mentality which Ranasinghe Premadasa damningly defined as “slavish…living in a way somebody else wants”. For obvious reasons, Sajith Premadasa was the obvious exception.

Grasping Geneva

Postwar, the hawks in the Rajapaksa administrations could not and cannot understand that the enlightened interest of the Sri Lankan State is inextricably linked with human rights, democratic and individual freedoms, and the cause of justice. Only then is sovereignty sustainable. Sovereignty not only means the sovereignty of the nation and/or the state but as a democratic republic, the sovereignty of the people, by which is meant the people as a whole, as well as the people as individual persons.

‘What is to be done’ and undone by the (returning) Foreign Minister, Prof. G.L. Peiris, to succeed in Geneva?

1. Sri Lanka needn’t be a Cambodia, Myanmar, or even another Pakistan, in its diplomatic stances. Sri Lanka doesn’t have to make up China’s undeclared Asian ‘Quad’. While China has the economic bandwidth to be the lender of first and last resort for Sri Lanka, it doesn’t have the politico-diplomatic bandwidth (as evidenced by the UNHRC vote of March 2021) and we don’t have the geo-strategic space, to keep us safe from external adversity. We have to broad-base our support beyond the bloc that votes automatically with China; a bloc which we may call that of ‘absolute sovereignty’ or in some cases, ‘absolutist sovereignty’. We must win (back) the majority of member states from the global South, our natural constituency (Geneva 2009).

2. The relationship with India can be reinvigorated by the full implementation of the 13th Amendment within an agreed-upon, compressed and declared time-frame, thereby redeeming the wartime pledges repeatedly made by President Mahinda Rajapaksa and the ‘troika’ (Basil Rajapaksa, Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Lalith Weeratunga) as reflected in the 21 May 2009 joint communique of the Governments of Sri Lanka and India.

3. The undertaking given to UN Secretary-General Ban ki Moon by President Mahinda Rajapaksa on 23 May 2009 must be fulfilled by the unambiguous and time-bound commitment to the verifiable implementation of the recommendations on accountability of the Commissions appointed by President MR (whose patriotic and nationalist credentials are beyond question). A credible domestic mechanism is also available in the twin proposals, one building on the other, presented to the Yahapalanaya Foreign Ministry in 2015 by the Attorney-General’s Department and prepared primarily by a respected current member of the Supreme Court bench, supremely—pun intended—competent in the UNHRC arena. It was rejected by the UNP PM and Foreign Minister.

4. Roll-back the militarisation of the civilian administration, a process of proliferation tracked and traced by the High Commissioner, the OHCHR and the UNHRC and which is now blatantly extended with the Emergency/Essential Services Regulations.

5. Reverse the shrinkage of the sphere of human rights and democratic freedoms and relax the heavy-handedness (e.g., the treatment of Hejaaz Hizbullah).

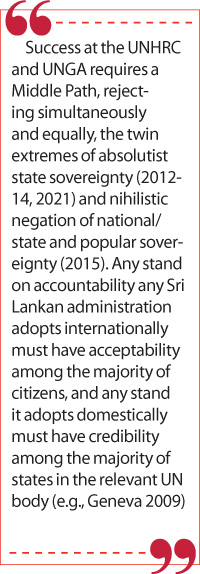

Success at the UNHRC and UNGA requires a Middle Path, rejecting simultaneously and equally, the twin extremes of absolutist state sovereignty (2012-14, 2021) and nihilistic negation of national/state and popular sovereignty (2015).

Any stand on accountability any Sri Lankan administration adopts internationally must have acceptability among the majority of citizens, and any stand it adopts domestically must have credibility among the majority of states in the relevant UN body (e.g., Geneva 2009).