Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Monday, 6 September 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

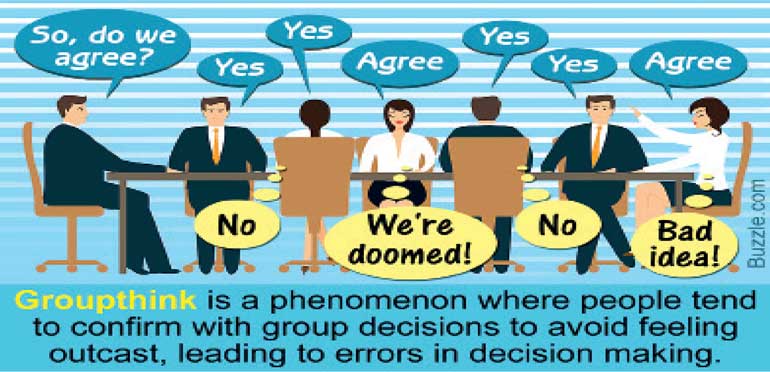

Groupthink occurs as a silent serpent that encroaches a synergistic team

Amidst the doom and gloom of COVID-19, taking timely decisions based on scientific data available is crucial. Having a holistic picture with multiple implications of decisions in mind is equally important. The tension arises in reaching consensus without critical analysis where a group of decision makers might end up showing ‘groupthink’ in action. Let us discuss the details in relation to the current context of combatting a contagion.

Amidst the doom and gloom of COVID-19, taking timely decisions based on scientific data available is crucial. Having a holistic picture with multiple implications of decisions in mind is equally important. The tension arises in reaching consensus without critical analysis where a group of decision makers might end up showing ‘groupthink’ in action. Let us discuss the details in relation to the current context of combatting a contagion.

Overview

When everyone unanimously agrees to something and if the decision is wrong, what would be the consequences? This is what the term ‘groupthink’ is all about. It is a term proposed by Irving Janis, a research psychologist at Yale University, in 1972. In his own words, “Groupthink is a quick and easy way to refer to the mode of thinking that persons engage in when concurrence seeking becomes so dominant in a cohesive ingroup that it tends to override realistic appraisal of alternative courses of action.”

We often hail teams as a great way to achieve results. We say with conviction that together everyone achieves more. There is a flip side to working together. Groupthink occurs as a silent serpent that encroaches a synergistic team. Teams and groups are often interchangeably used to describe a set of people working together. A group is widely known as a set of two or more individuals interacting and interdependent with each other in achieving a common objective. A team is one step ahead. I would simplify a team as a group with synergy.

“Synergy means that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It shows that the relationship, which the parts have to each other, is a part in and of itself. It is not only a part, but also the most catalytic, the most empowering, the most unifying, and the most exciting part.” That is how Stephen Covey, in his bestseller ‘Seven habits of highly effective people’, described synergy. It is very much in demand but overdosing of it can create problems.

Glimpses of groupthink

Teams have a danger of getting affected by groupthink. It is a case of everyone unanimously agreeing for something fundamentally wrong. It is known as a type of thought within a deeply cohesive group whose members try to minimise conflict and reach consensus without critically testing, analysing, and evaluating ideas. In other words, team members support an idea or a viewpoint without one’s critical analysis. It can happen in departments, private institutes, public organisations, task forces and even in cabinet meetings.

In essence, contradictory views are suppressed or self-censored in the guise of maintaining solidarity and the result might be disastrous. It may lead to an illusion of unanimity where everyone feel that they have taken the right decision. It could be a case of stereotyping where an alternate view is ignored and suppressed where everyone is expected to agree. Such a scene may easily lead to self-censorship where one opts to stay quite rather than authentically expressing oneself and getting bashed for doing so.

It might create false optimism that the term is rock solid in taking decisions in showcasing the unity to the outside world. Obviously, there is a direct pressure to conform, particularly is often placed on members who pose questions, and those who question the group might be perceived as disloyal or disobedient. This goes with the golden saying, “When everyone thinks alike, no one really thinks”. World history is fully such cases.

Pearl Harbour attack: This can be interpreted as a classic case of groupthink. Pearl Harbour, an American naval base near Honolulu, Hawaii, received a surprise attack by Japanese forces on 7 December 1941. The massive destruction was not foreseen or anticipated by the panel of experts who advised President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Their unanimous suggestions with complacency grossly undermined the craft plans and precise execution of Japan. Declaring war on Japan on the day after was far more reactive than proactive.

Bay of Pigs fiasco: It was in April 1961 that there was a failed attack launched by the CIA during the Kennedy administration to overthrow Cuban leader Fidel Castro. The advisors to President Kennedy were unanimously of the view that it will be a definitive strike that would be a breakthrough, underestimating the strength of Castor’s troops. The results proved otherwise. Ironically Castro comfortably survived many US presidents thereafter. However, the invasion did not go well.

Space Shuttle Challenger disaster: Explosion of the US space shuttle orbiter Challenger, shortly after its launch from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on 28 January 1986, which claimed the lives of seven astronauts. Despite clear technical concerns, ‘managers’ silenced ‘engineers’ in reaching a false consensus to give green light to send off the shuttle. The investigation commission appointed later heard disturbing testimony from a number of engineers who had been expressing concern about the reliability of some specific components for at least two years and who had warned superiors about a possible failure the night before the shuttle was launched. No wonder that the commission recommended to tighten the communication gap between shuttle managers and working engineers.

From Saigon to Kabul: Though debatable, the unsuccessful wars in Vietnam and Afghanistan could also be attributed to some kind of groupthink. Defensive excuses by rulers, aftermath of a disaster, do not justify the inappropriate decisions taken with consensus of all involved. We saw in the media, how desperate Afghans swarmed the runway of the city airport, some even clung to the undercarriage of a c-17 transporter, falling to their deaths.

UK lockdown criticised by Cummings: Coming to a more recent event, there is a growing criticism of how the UK government has been tackling the pandemic. Dominic Cummings, former chief advisor to Prime Minister UK, mounted a systematic attack on the decisions of the government and its scientific advisory groups during the pandemic. These decisions, he repeatedly suggested, were a result of ‘groupthink’. According to the Guardian newspaper, Cummings used the term over 15 times in showcasing the folly of some collective decisions.

Asch Effect as an explanation

Dr. Solomon Eliot Asch, a pioneer in social psychology engaged in experiments to demonstrate the influence of group pressure on opinions. The original experiment that led to the naming of Asch Effect, was conducted with real participants, and assigned players, to observe the conformity tsking place. The ‘critical trials’ aimed to see whether the real participants would conform to the wrong answers of the confederates and change their answer to respond in the same way, despite it being the wrong answer.

Why did the participants conform so readily? When they were interviewed after the experiment, most of them said that they did not really believe their conforming answers but had gone along with the group for fear of being ridiculed or thought ‘peculiar’. A few of them said that they really did believe the group’s answers were correct. Dr. Asch suggested two possibilities:

Informative conformity: “I guess you know better than me. Hence I go with you.” This is when a question was asked, you might not know the answer and when the members give same consistent answer before your turn comes, you tend to trust that it is the correct answer. Perhaps, junior managers endorsing the decisions of their senior managers assuming that they know better could be such a case.

Normative conformity: “I know you are wrong. But I do not want to upset my relationship with you. Hence I go with you”. You know for sure that the consistent answer given before your turn comes is wrong and you know the right answer, but to maintain consensus without creating a conflict, you agree with them in telling the wrong answer. This could be a cultural phenomenon with a dominant leader who wants agreement to his or her views always.

Despite some criticisms, the Asch conformity experiments are among the most famous in the history of psychology and have inspired a wealth of additional research on conformity and group behaviour. This research has provided important insight into how, why, and when people conform and the effects of social pressure on behaviour.

Relevance to Sri Lanka

Managers see the truth but telling the truth might be politically disadvantageous at times. Organisational politics where might is perceived as right, endanger the critic and the analyst. “Yes Sir, Yes, Sir, Three Bags Full” is no more a mere nursery rhyme but has become a popular managerial response. What Andy Stanley, a leadership thinker said makes sense here. “Leaders who do not listen will eventually be surrounded by people who have nothing to say.”

I am not trying to be pessimistic here. Perhaps the starting point could be to be aware of possible breeding grounds of groupthink, leading to Asch effect. The maturity of separating a ‘point’ from the ‘person’ and constructively debate the points without getting into personal rivalry are the competencies high in demand.

With ongoing debates of the good and bad of a lockdown, the scientific facts and economic realities should be holistically viewed. The expertise of scientists, healthcare professionals, economists, administrators, and managers alike should be sought without any marginalisation. In essence, they should be aware of the possible pitfalls of groupthink and the temptations of contributing to the Asch effect.

Way forward

“The main misfortune, the root of all the evil to come, was the loss of confidence in the value of one’s own opinion. People imagined that it was out of date to follow their own moral sense, that they must all sing in chorus, and live by other people’s notions, notions that were being crammed down everybody’s throat.” That is how Boris Pasternak, author of much acclaimed novel, Doctor Zhivago opined referring to prevalent groupthink in Russia, a long time ago. Much food for thought with relevance to local and regional realities.

Conformity is fine but not at the expense of constructive criticism. Decision makers in all fronts need confidence to be truthful to themselves, which is a revelation of their character.

(Prof. Ajantha Dharmasiri, former Director of Postgraduate Institute of Management, can be reached through [email protected], [email protected] or www.ajanthadharmasiri.info.)