Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Monday, 2 October 2023 01:35 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

|

Has the economy been assassinated?

Has the economy been assassinated?

A popular belief among many Sri Lankans today is that Sri Lanka’s economy has been assassinated beyond resurrection. This belief is based on the severest economic crisis and economic depression in its post-independence history which the country is undergoing today. Many have tried to point the fingers at the identified assassins too. Connected to this conception is the bankruptcy of the central government because it cannot service its domestic or foreign debt – the work involving the payment of interest and repayment of the principal.

But what we mean by bankruptcy is a situation in which an individual, an entity or an organisation including the government does not have sufficient earning assets to pay out to liability holders. Since liabilities to outsiders are more than the assets, its net worth is negative. As a result, the affected party cannot continue its business or in the terminology of business, it is not a going concern. If it is a business organisation, in terms of the current laws, it should be compulsorily wound up. Sri Lanka Government has not fallen to this depth so far. It can still raise revenue through taxation though that level is insufficient to meet all its expenses.

To meet a part of those expenses, it can still borrow from the local market without unduly increasing interest rates. To finance some of the projects, it can borrow from the multilateral lending institutions like the World Bank, ADB, or IFAD. But it does not have enough cash to make out all the payments it should do. Hence, the problem faced by the Government is more of a negative and inadequate cash flow than being completely bankrupt.

To alleviate the cash flow problem, it has already suspended the servicing of commercial loans mainly through the issue of international sovereign bonds and those loans obtained from friendly countries like India, China, Japan, and so on commonly known as bilateral sources, on the external front, and rescheduling a part of the domestic debt, on the national front, supported by a bailout package from IMF. This has been strengthened by the introduction of the most stringent import and exchange controls which a government has resorted to in the recent years. The process is continuing, and the country is not yet out of the woods. The outcome of the process is also not yet known.

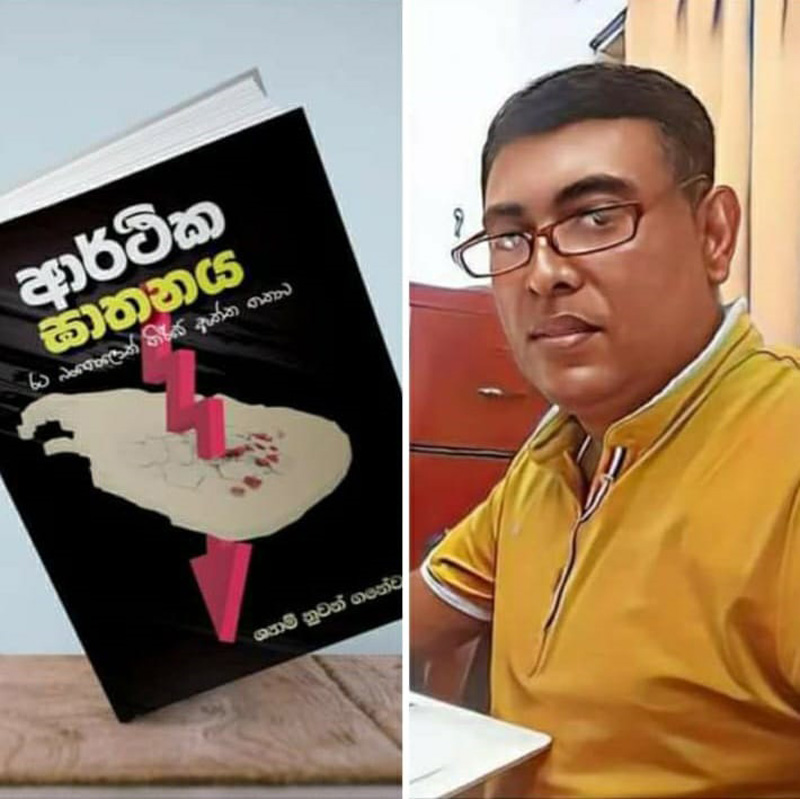

Shyam Nuwan Ganewattha’s book on assassination of the economy

In this backdrop, an economics journalist who writes to media and addresses public forums – Shyam Nuwan Ganewattha – has released a book under the title ‘The assassination of the economy: The true story of making the country bankrupt’ recently. He says that the bankruptcy of the country is not accidental or spontaneous. It is man-made due to the wrong policies adopted by successive governments in the recent few years. It is the cumulative outcome of many such policies. He has not tried to identify those responsible. However, he has narrated the story in chronological order from around December 2019 so that the readers could make the judgment for themselves.

He says, regarding the shortage of foreign exchange reserves, the top leaders of the Government in 2021 and 2022, along with those in the Central Bank, had pleaded with friendly countries for assistance, but those pleadings did not bring in any help. Hence, the inevitable result was the suspension of the foreign debt servicing, shortage of essential imported items like fuel, cooking gas, and medicines, long queues for same products, long hours of power cuts, and a crippled industrial base due to lack of the needed raw materials.

The book has reproduced an interview with the rescue man of the economy – Central Bank Governor Dr. Nandalal Weerasinghe – who has claimed that he had inherited an economy which had already been assassinated. This may be too strong a statement because if the economy had already been assassinated, there is no prospect of resurrecting a dead economy. A more appropriate description would have been that the economy had been crippled and making it stand on its own feet had been a gargantuan task.

Ganewattha’s book is an easy reader and meant for the ordinary public. Ganewattha using his versatile journalistic language has met this objective. Hence, it contains a simple analysis that can be easily understood by ordinary readers. Yet it provides an opportunity for us to examine the real causes for the crippling of the economy, how it was orchestrated by policymakers, how it degenerated gradually at first and pretty fast later, and how the warning signs were ignored by those who are responsible for taking corrective action.

Crippling the economy by rising public debt

The main contributor to the present economic catastrophe is the ever-rising public debt – defined as the debt contracted by the wider public sector that is made up of the central Government, the Central Bank, State banks, other State enterprises, and the private sector on the strength of guarantees issued by the Government. This does not mean that borrowing is an evil activity. If one does not have enough savings, he could tap the savings of others to finance his expenditure programs. However, a prudential requirement is that money so borrowed should be used for productive investment, and not for continued consumption, enabling the borrower to repay the loan with interest as promised. If prudence is practiced in this manner, money borrowed for productive investments does not pose a problem.

Surplus budgeting by ancient Lankan kings

Sometimes I am asked the question by interested readers that if the ancient Lankan kings could build reservoirs as large as oceans – for example King Parakramabahu I could build the Parakrama Samudraya – without borrowing from abroad, why should we do so in the present period. This is a very pertinent question, but we cannot compare the public finances of ancient Lankan kings to those of the modern-day democratic governments.

In ancient times, there was an inclusive tax base under which all citizens – farmers, businessmen, and aristocrats except religious institutions – paid taxes to the king. They were accumulated in the Treasury of the king and the power of the king was measures in terms of the value inside the treasury. Hence, the king spent less than what he got as taxes. In today’s parlance, ancient kings had surplus budgets whereas modern democracies do have deficit budgets. Taxes in ancient times were also high in ancient times. Farmers paid on average about 30% of their crops as taxes to the king.

In addition, there was a system of free royal work, known as Raajakaari System. In that system, every able-bodied person should provide free service to the king for about three months. This is equivalent to the polls taxes that are being imposed on individuals by modern democracies. Hence, the Raajakaari System was equivalent to an additional income tax of 25%. As a result, the average tax rate applicable to an ordinary citizen was equal to about 55%. With such a system of surplus budgets and high tax rates, ancient kings did not have to borrow to finance their capital expenditure programs. But kings were very prudent in using those scarce resources to build productive capital works.

|

Fiscal prudence by colonial rulers

Similar prudence was exercised by the colonial rulers in borrowing for financing capital expenditure programs. An example in this connection is the financing of the old Ceylon’s railway system. As revealed by the Colombo University’s history don, Indrani Munasinghe, in her 2002 book The Colonial Economy on Track, the Colombo-Kandy railway line was constructed by borrowing £ 3.5 million at interest rates ranging between 3-6% from the London capital market and Rs. 2.5 million locally. When the request for borrowing was presented to the Colonial Secretary, he approved it on three conditions: the loan proceeds should be used only for building the railway line, it should be self-financing, and a sinking fund should be established out of the surplus moneys to repay the principal of the loan and the interest thereon.

This practice was followed for other railway lines too. Hence the borrowings were prudently financed by the colonial rulers and in 1905 when the project was completed, the outstanding loans amounted to Rs. 39 million and the funds in the sinking funds amounted to Rs 41 million. Hence, the debt servicing was not a burden to general taxpayers of the country.

Abolition of sinking fund system in 1984

Building a sinking fund is a must if a borrower is desirous of paying back a loan without getting into loan default. The colonial administration in ancient Ceylon just did that. They incorporated it as a legal requirement when raising a loan by the Government by providing for the same in the Registered Stocks and Securities Ordinance or RSSO under which the Government raised medium to long-term loans.

Accordingly, when they handed the reign to Ceylonese in 1948, there were two specific sinking funds, one for foreign loans and the other for domestic loans. Foreign loans amounted to Rs. 125 million or 4% of GDP. But the foreign currency sinking fund had resources amounting to Rs. 43 million bringing down the net borrowing to Rs. 82 million or 3% of GDP. With respect to domestic loans, the outstanding balance was Rs. 368 million or 13% of GDP. The rupee sinking fund amounted to Rs. 47 million reducing the net domestic borrowing to Rs. 320 million or 11% of GDP. This prudent practice was continued by local rulers after Ceylon got independence from Britain in 1948.

However, due to the foreign exchange shortage faced by the country, the rulers had to abandon the continuation of the foreign currency sinking fund in early 1960s. But they continued to maintain the rupee sinking fund because it provided a partial relief to debt servicing. Accordingly, as at end-1983, the outstanding rupee loans amounted to Rs. 31 billion but the sinking fund of Rs. 11 billion provided a cover of 35%. The moneys in the sinking fund were reinvested in new government securities so that there was a reflow of funds to the Treasury. But it helped to introduce discipline to the Ministry of Finance.

Flimsy arguments for abolishing sinking fund system

But as from 1 January 1984, the Government decided to abolish the sinking fund system on a recommendation by the Monetary Board of the Central Bank. The reasons adduced were short-sighted and lacked a prudent long-term vision. One reason was that it would help the Government to reduce the size of the budget since contributions to the sinking fund to cover interest were charged to recurrent expenditure and capital part to the capital expenditure. When you remove both, the size would fall. Another argument was that there was no necessity for a sinking fund to ensure reflow of funds to the Government’s borrowing program because 97% of the contributions have been made by captive sources which had to do so compulsorily in terms of their statutes.

A third argument was that the sinking fund arrangement was just a book-keeping without transfer of real cash from the Government to the fund and vice versa. Hence, there was not any economic impact arising from the system. A fourth argument was that the abolition of the sinking fund system will reduce both the gross expenditure and the gross borrowing of the Government. A fifth argument was that the Government can always refinance the interest payments and maturing government securities and therefore there was no risk of servicing the public debt.

These are all flimsy arguments because they had overlooked the more important role of the sinking fund system enforcing discipline on the use of public finances of the Government. It is the lack of discipline that contributed to the ballooning of public debt beyond the ability of the Government to service them without refinancing the same. When the refinancing flows ceased, the Government could no longer service the debt and had to suspend the debt repayment pending debt restructuring. The rating agencies and IMF had continuously declared that Sri Lanka’s public debt has been unsustainable on this ground.

It is not clear why the Monetary Board which is supposed to be looking at the long-term effects of economic policies made such a grave error of judgment in recommending to the government to discontinue the sinking fund system. Making prearrangement to repay a debt is a prudent measure taken by any long-sighted borrower.

|

Better to restart sinking funds for new loans

Today, it is impossible to go back to the sinking fund system with the massive debt of the wider public sector of the country. However, it is prudent to cover every new loan to be contracted by the central government and all other public sector entities with a mandatory sinking fund requirement. This is specifically important in the case of borrowings by public sector entities and loans raised by the private sector on a guarantee by the Government. Parliament which takes pride in being the manager of the public finances of the country should see that this arrangement is followed in the case of every loan to be raised. Otherwise, it is impossible to avoid being a bankrupt country again in the future.

This is a good learning experience for the present Governing Board and the Monetary Policy Board setup under the new central banking arrangement. They may take decisions today just looking at the benefits in the present period. But their adverse implications may fall on the economy many years after the decision has been made. As Frederic Bastiat said in 1850, a good economist will look at not only what is being seen today but also what is to be foreseen in the future because of the policies implemented.

Otherwise, the present policymakers may run the risk of being named assassins in the future.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)