Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Saturday, 12 May 2018 00:29 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Saturday’s elections to the 224-member State Assembly in the South Indian State of Karnataka, are critical for both the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) ruling India, and the Congress which is the ruling party in Karnataka and is the main Opposition in the Indian parliament.

The BJP is hell bent on winning the Karnataka elections to break the “Southern Barrier”. It has been unable to capture or retain power in the Southern States of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Kerala and establish itself as a truly all-India party, a status only the Congress enjoys.

And the Congress is desperately fighting to retain its traditional turf in Karnataka and South India and use this as a springboard to drive the BJP out of its strongholds in North India.

The way Karnataka polls go will also show, in a way, which way the political wind will blow in the State Assembly elections in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chattisgarh, which are due later this year. And then there are the all- important parliamentary elections due in May 2019 which are critical for both Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Congress chief, Rahul Gandhi.

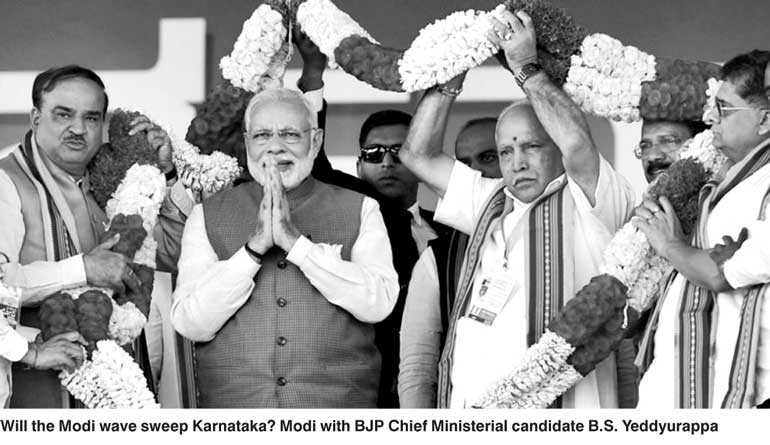

The State Assembly elections will tell whether the “Modi wave” which has been sweeping India since 2014, giving the BJP a footprint in 22 out of 29 States, is waxing or waning in the face of a mounting challenge from the Congress led by Rahul Gandhi.

The BJP, which seemed unchallengeable in 2017, following its sweep in the Uttar Pradesh elections, is unsteady come 2018. It is forced to deploy all its resources into elections campaigns.

While Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed 19 rallies covering 18 assembly constituencies in Karnataka, Congress President Rahul Gandhi addressed 17 rallies in 15 constituencies.

Unseemly campaign

The BJP’s campaign in Karnataka has been ugly to say the least. Caste, community and religion have been used to the hilt, making the 2018 polls the most divisive in the State’s history. It portends worse things to come if the trend is not reversed quickly.

To turn the contest into a Hindu-Muslim fight, the Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister challenged the incumbent Congress Chief Minister B.S. Siddaramaiah to prove that he is a “true Hindu” by banning beef in Karnataka. The Karnataka BJP had put out tweets calling Siddaramaiah “pro-Jehadi” with the hashtag #jihadimuktKarnataka (Jehadi-free Karnataka).

One of the tweets mentions how «fear of annihilation grips every Hindu household in Karavali (a place in Dakshina Kannada district known for Hindu-Muslim tension). The BJP›s Dakshina Kannada MP Nalin Kumar Kateel dubbed Siddaramaiah as «narahantaka›› (killer of human beings) and referred to him as «Sultan Siddaramaiah›› akin to the 18 th.Century ruler of Karnataka Tipu Sultan who indulged forcible conversions to Islam in coastal Karnataka.

Siddaramaiah had planned to commemorate Tipu Sultan in a grand fashion on the grounds that he resisted the British and died fighting them in Srirangapattnam. But this move was opposed by the Hindu Right wing.

The BJP’s game plan was to continuously accuse the Congress of blatant minority “appeasement”. The BJP claimed the Congress has a secret deal with the Muslim Social Democratic Party of India (SDPI), the political wing of the Popular Front of India (PFI). The BJP has been demanding a ban on the PFI, as a “terror outfit”.

However, the BJP itself had floated a dubious organisation called All India Mahila (Women’s) empowerment Party (MEP) led by the hijab-clad business women, Nowhera Shaik, to get Muslim votes in all the 224 constituencies.

However, the BJP itself had floated a dubious organisation called All India Mahila (Women’s) empowerment Party (MEP) led by the hijab-clad business women, Nowhera Shaik, to get Muslim votes in all the 224 constituencies.

However, experts say that the BJP’s Hindu-Muslim communal card might work only in 20 Dakshina Kannada constituencies, due to the mixed population of Hindu, Muslims and Christians there who compete with each other in the economic sphere.

The rest of Karnataka is largely agricultural and dominated either by the Lingayat caste (as in North Karnataka) or by the Vokkaliga caste (in South Karnataka). Among these two castes the issues relate to caste and regional identity, political power and economic development.

Both the BJP and Congress candidates for the Chief Minister’s post are Lingayats. To please the Lingayats, Chief Siddharamaiah had given in to the demand of a section of the Lingayats to be notified as a non-Hindu minority community. The classification as a “minority” will entitle them to certain constitutional rights.

But the BJP’s B.S. Yeddyurappa has condemned the move as a nefarious attempt to weaken the majority Hindus in favour the Muslims and Christians.

The third factor or personality in the Karnataka elections is H.D. Deve Gowda, a Vokkaliga leader who was Prime Minister of India in the mid-1990s. Head of the Janata Dal (Secular), Gowda is now a marginal player in South Karnataka. But he could be a kingmaker if the polls return a hung Assembly.

Pre-election polls say that there is only a 2% difference in the vote share between the Congress and the BJP, and that the outcome will be a hung assembly.

But many perceptive watchers believe that the Congress will retrain power in the State. Anti-incumbency is not pronounced this time. Chief Minister Siddaramaiah’s populist schemes, good macro-economic performance and his generally scandal free administration have won him praise.

While the tradition in Karnataka is to change the government every five years, this time, it could be different due to the “inclusive and welfare schemes rolled out in the last five years,” says a commentator.

These are, free distribution of rice, subsidy for milk, hostels for students, agricultural e-markets, interest-free loans to farmers, reservation for the lowest castes in government contracts, low-cost meals in urban areas and increased budgets for religious minorities.

At the macro-economic level, Karnataka ranked 11th in investment attraction in 2013 when Yeddyurappa’s BJP regime ended. But in 2018, the State became a top investment destination. Energy production capacity increased from 5,361 MW in 2013 to 9,349 MW in 2018.

The Siddaramaiah Government had also played on regional sentiments by adopting a separate flag for Karnataka State and asking the Central Government to provide “separate religion” status to the Lingayats.

Siddaramaiah’s tenure has been largely controversy free. In contrast, Yeddyurappa’s BJP Government between 2008 and 2013 was marked by authoritarianism and scandals which resulted in Yeddyurappa’s being jailed for 25 days in 2011.

The BJP lost the elections in 2013 but thanks to the “Modi wave”, it came back strongly in the May 2014 Parliamentary election to win 17 out of the 28 Parliamentary seats in the State.

However, in the State Assembly elections the criterion is performance at the State level presumably. Here is where Siddharamaiah and the Congress score over the BJP and Yeddyurappa. But the question as to whether the “Modi wave” unleashed in 2014 is still strong, will be answered in the next few days.