Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Thursday, 12 May 2022 01:19 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A perfectly competitive free market system is often regarded as the most efficient economic system. However, the free market does not always result in the optimal allocation of resources. The market becomes inefficient in the presence of market failures such as natural monopoly, imperfect information, externalities, or public goods. As a result, State intervention is justified to correct these market failures and also to a certain extent, improve social equity.

A perfectly competitive free market system is often regarded as the most efficient economic system. However, the free market does not always result in the optimal allocation of resources. The market becomes inefficient in the presence of market failures such as natural monopoly, imperfect information, externalities, or public goods. As a result, State intervention is justified to correct these market failures and also to a certain extent, improve social equity.

Therefore, the State is generally allowed to enact laws and regulations, sometimes even participate in the market to enhance the wellbeing of the people. Nevertheless, State intervention distorts the market away from its equilibrium path. However, these distortions are intended to benefit the public. Yet, in many instances, particularly when the markets are distorted for a longer period, they fail and can cause a bigger crisis.

Sri Lanka is currently facing its worst economic crisis in its post-independence history. A major cause of this prevailing crisis is extensive State intervention, resulting in prolonged market distortions. Currently, the sectors with high market distortion include foreign exchange, public transportation, power and energy. However, various other sectors are also distorted due to regulations and protectionist tariffs. The State has been distorting these markets for a prolonged period in the name of enhancing the welfare of the people or even sometimes due to pressure from various sects of society and businesses.

This article will focus on the market distortions particularly in the foreign exchange market and show how it contributed immensely to the current crisis. In addition, this article goes on to explain how the economic problems can be solved when markets are truly free from any distortions.

Sri Lanka’s forex problem, government actions and the resulting crisis

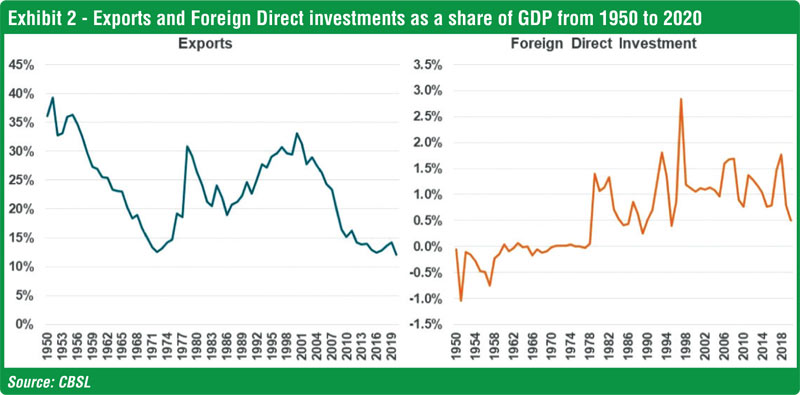

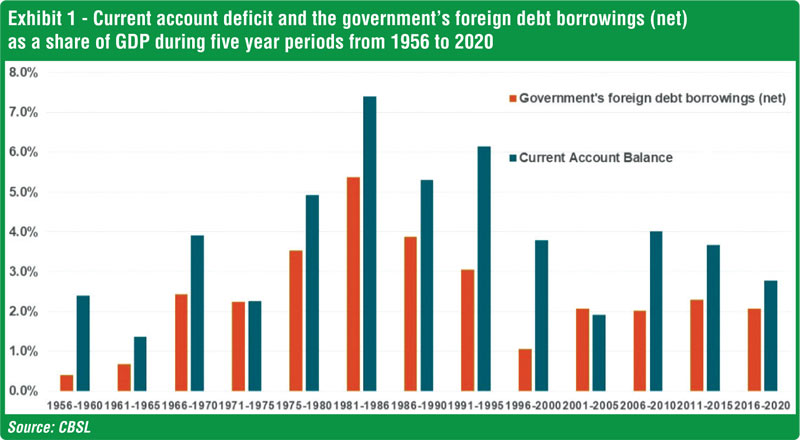

Since 1957, Sri Lanka has had a current account deficit in all but two years. During the period from 1957 to 2020, the current account deficit averaged 4% of GDP. Put in simple terms, this means Sri Lanka has consumed more from the rest of the world than it produced (and sold to the rest of the world). This also means that previous generations on average consumed around 4% more than they actually produced every year. This excess consumption was possible because Sri Lanka financed its current account deficit with other foreign exchange inflows mainly from foreign loans.

From 1957 to 2020, foreign loans obtained by the government financed 64% of the incurred current account deficit (The rest was mainly financed by foreign direct investments and debt obtained by the private sector from abroad). In other words, previous generations did not pay for what they consumed in excess of their production but passed it on as debt to the next generations. As the people continued to consume in excess (by incurring a current account deficit), the foreign debt only continued to increase every year, from 5.3% of GDP in 1957 to 40.4% in 2020.

Up until 2007, the current account deficit was financed via foreign loans at concessionary terms from development agencies. After 2007, the country borrowed at higher interest rates in the international capital markets (in the form of International Sovereign Bonds) to sustain their excess consumption. As a result, foreign debt continued to increase.

Of course, economists and the decision makers were aware of the unsustainable nature of Sri Lanka’s foreign debt. To address this issue, in 2019, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka and the Ministry of Finance together released a Medium-Term Debt Management Strategy to reduce the foreign debt as a share of GDP from 45.1% to 38.5%.i

The long-term solution to this foreign exchange problem was to expand exports and to attract new non-debt foreign investments into the country. However, in reality it is not easy to improve exports and bring in investments. Successive governments tried this strategy for decades. While there were sporadic spikes in exports, the overall trend has been declining. Additionally, foreign direct investments increased only marginally.

As there were no significant improvement in exports and FDI to bridge the current account deficit, Sri Lanka increasingly became reliant on international borrowings to finance the current account deficit. The yearly incurrence of a current account deficit even became a norm, as policymakers got fixated on the idea that Sri Lanka is an economy with a current account deficit and borrowing is necessary to balance the country’s forex account. Hence, Sri Lanka continued borrowing every year to refinance its debt maturities and to pay for the current account deficit.

However, this changed at the end of 2019, when Sri Lanka lost its ability to borrow more in the international markets. Mainly due to the newly elected Government’s populist fiscal stimulus agenda that promised to increase the country’s dampened GDP growth. This fiscal stimulus included a cut in tax revenues by one thirdii and increase in expenditure by 15%.iii Overall the fiscal stimulus increased the budget deficit from 6.8% in 2019 to 14% in 2020 and is expected to remain above 10% in the coming yearsiv. This was done in such an ad-hoc manner with hardly any reflections on the repercussions it would have on the Government’s debt sustainability. As a result, international bondholders lost confidence and Sri Lanka’s credit rating were downgraded. Consequently the Government was unable to borrow more from the international markets as foreign lenders no longer trusted the Government to payback their debt.

The lack of access to international markets created a foreign currency shortage. Not only did Sri Lanka have a current account deficit to finance, but also increased foreign debt repayments due in the coming years — which is far greater than the yearly current account deficit. The annual debt repayments due is around $ 4.4 billion on average (during 2021 to 2025)v, while the current account deficit is only around $ 2 billion on average (during 2018 to 2020). Although this problem was evident from the beginning of 2020, its effects started to affect the public only in the beginning of 2022, when the country ran out of foreign currency to pay for essential goods such as; fuel (which is also mainly used to generate power), medicines and essential food items.

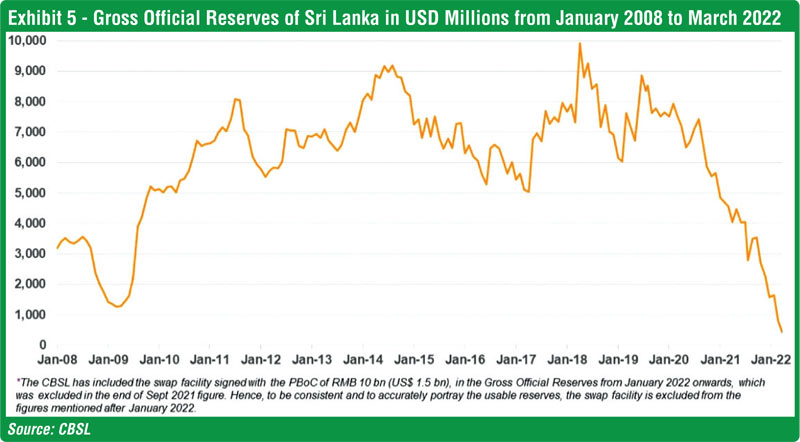

During the last two years, the Government mainly used up the reserves to finance the debt repayments and the current account deficits. Hence, the external usable reserves dropped from $ 7,639 million at the end of 2019 to around $ 439 million (which is adequate for only 0.25 months of imports) at the end of March 2022.vi This is the lowest level of usable reserves have dropped to, in the history of Sri Lanka. Since, the reserves reached a rock bottom, the Government can no longer release forex for essential imports resulting in severe shortages of goods in Sri Lanka. In the coming months this problem will become worse unless major bilateral partners such as India and China bail out Sri Lanka endlessly.

Distortions in the foreign exchange market

In a market economy, shortages do not exist. There is always someone willing to sell at a price and another party willing to buy at that price. Simply, the demand and supply interactions will determine the equilibrium price and the quantity of the good. Therefore, in a free functioning forex market, shortages of foreign currency should not occur. Anyone should be able to buy foreign currency freely and import any good from abroad.

However, in the context of Sri Lanka, the major shortage of dollars in the market is a result of State interventions in the forex market.

In the last two years, the central bank distorted the forex market in an extremely harsh manner. The distortions included introduction of regulations such as a minimum cap on the foreign exchange rate and rules requiring forced conversion of export proceeds. The existence of these rules meant that it was impossible for the market forces (demand and supply) to interact and decide on a price. Hence, leading to acute shortages of foreign exchange and the creation of informal parallel markets — selling foreign currency at a higher rate.

Other distortions that have been performed by the State for decades, included borrowing foreign currency debt and engaging in buying and selling of currency in the forex market. As opposed to the regulations mentioned previously, these distortions still enable the demand and supply in the market to decide the price of the foreign currency. However, they alter the demand and supply volumes in the market. Hence, indirectly, altering the price of the foreign currency.

The Government borrowing foreign currency debt increases the overall supply of the foreign currency in the market and keeps the price of the foreign currency lower. In the absence of a foreign loan, the country would have had to pay for its imports entirely from the export proceeds. Thus, reflecting a true market determined price for the foreign currency — only with the interactions of the demand and supply created by the importers and exporters.

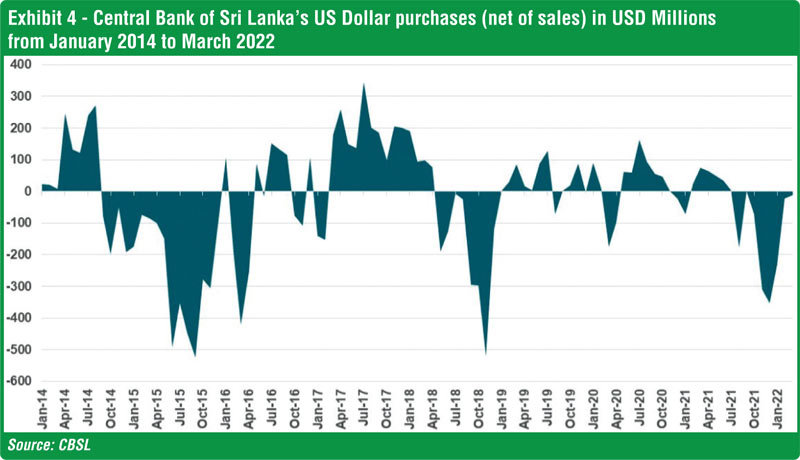

The central bank engages in buying and selling of foreign exchange to reduce the fluctuation of the currency. While short term interventions (usually few weeks) could be justified to a certain extent for curtailment of unwarranted market speculations.

A longer-term term (more than a month) participation is highly detrimental to the free functioning of the market and can even be costly to the Government. Since 2013, there have been three instances in which the Central Bank sold large amounts of US dollars for a prolonged period to stabilise the exchange rate; (1) during September 2014 to April 2016 in which $ 4,356 million was sold to the market, (2) during May 2018 to December 2018 in which $ 1,578 million was sold and (3) during August 2021 to March 2022 in which $ 1,176 was sold.

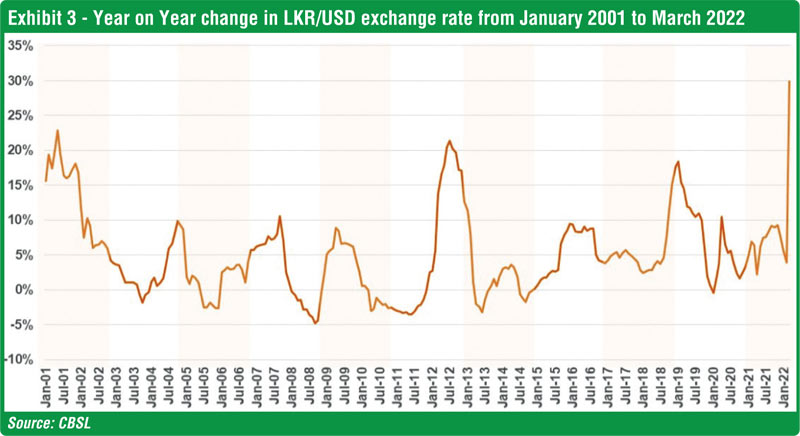

These three periods coincided with political changes in the country. Sri Lanka had a presidential election in January 2015 and a parliamentary election in August 2015 which paved the way for a new government. In November 2018, Sri Lanka faced a constitutional crisis in which the president sacked the incumbent prime minister and nominated a new prime minister from the opposition party. In November 2019, a new government was elected which enforced radical economic policy changes leading to the current crisis. During these three periods, the governments in power halted the increase in the exchange rate for months, by supplying dollars to the market. Although from 2020 onwards more extreme measures were deployed. The exchange rate was controlled in these periods to avoid public loss of confidence in the government.

This practice of central banks selling dollars to the market not only distorts the market but also reduces the reserves of the country. It is highly detrimental when foreign reserves built up using debt, is used to pump currency into the market to keep the exchange rate lower. It is similar to borrowing money and throwing it out of the window, just to keep the exchange rate lower.

Furthermore, the exchange rate movements show that the Sri Lankan rupee does not depreciate significantly every year. There has been a significant depreciation only every two or three years. This clearly indicates that the Central Bank controls the market by selling dollars to maintain the exchange rate for a certain period as long as there are sufficient reserves in custody. When the reserves continue to deplete the Central Bank is compelled to halt the selling of dollars to maintain the rate, resulting in the rupee depreciating. Likewise, when there is pressure for the rupee to appreciate (due to global depreciation of the US dollar), the rupee remains stable as the Central Bank engages in purchasing more dollars from the market.

All these interventions can only control the exchange rate for limited time period, in the long run the exchange rate somehow reverts to its true value. Economic theory suggests that according to the “law of one price”, the percentage change in the nominal exchange rate between any two currencies will equal the difference between the percentage changes in the price levels of the two corresponding countries”vi. Data from the last 20 years (2000–2019) shows that the average annualised inflation differential of Sri Lanka and the United States amounts to 5.8%. The annualised rate of depreciation of the Sri Lankan Rupee against the United States Dollar was 4.9% in the same periodvii.

The justification for distortion of the foreign exchange market

A free float of the currency can increase the price of the foreign currency to unprecedented levels, when the supply is lower than the demand. At present the demand for foreign currency is high in Sri Lanka because the current account is in a deficit. In addition, the Government also wants to buy more dollars to payback its debt, this can increase the demand and the exchange rate further. Currently, this is what is happening in Sri Lanka. After the Central Bank lifted its minimum cap on the USD price in the beginning of March 2022 — the exchange rate skyrocketed. The official rate increased from Rs. 203 (capped amount) to around Rs. 300 per USD at the end of March 2022.

Hence, free floating of the currency, with such high demand for foreign currency, can increase the cost of imported goods to unprecedented levels, especially essential goods that are not produced in the country. The fear of creating inflation and raising the cost of living, especially for the poor, has been the major reason for controlling the exchange rate.

Yet, controlling of the exchange rate can only be done by borrowing more foreign exchange and pumping it into the market to keep the prices low. This form of policy is meant to stabilise the cost of living in the present and to postpone the balance of payment problem to a future date — in the hopes of boosting the exports and foreign investments in the future. However, there is no credible reason to believe the Government can solve this problem now as opposed to the past.

Furthermore, predicting the future economic outcome is unviable. It is highly dangerous to make policies in the current time based on the optimistic hopes of the future. The foreign exchange problem would have been dealt much more simply if there was less debt to be repaid in the future. The further we control the market, the more we exacerbate this problem, and increasing the burden that future generations will have to shoulder.

How would the absence of market distortion improve the situation in the foreign exchange market?

If the markets were not distorted and a free float of the currency was practiced, the outcome would have been much different. A current account deficit, due to imports exceeding exports (assuming no government foreign debts repayments), results in a higher demand for foreign currency (importers demand) than the supply of foreign currency (provided by the exporters, remittances and other inflows). Then the price of foreign currency would increase. The consequence of this would be;

Firstly, the imported good will be relatively more expensive compared to locally produced goods. This in turn will reduce the demand for imported goods, based on the elasticities of those goods. Demand for items such as fuel and other necessities would not reduce much initially, however most other goods that can be substituted easily will experience demand reduction. For example, maybe the price of bread and all wheat-based bakery products would increase with the increase in exchange rate. This acts as a signal for the Sri Lankan consumers that they cannot afford these products unless they export more goods abroad. Now the consumers of bread, if they cannot afford it, may have to change their consumption pattern towards more locally produced food items. In contrast, controlling the exchange rate for decades, has resulted in cheaper imported products and the society has got accustomed to consuming such goods. Of course, the people that depend on wheat-based products would suffer more, but at the end of the day they need to move away from such unsustainable consumption of foreign goods to cheaper local alternatives.

While it may be easy to shift consumption pattern of certain goods in the short run, it can take a longer time to shift consumption patterns of certain other goods. However, the market reflected high price is vital to make that shift. For example, in the consumption of fuel — to reduce the consumption people need to reduce the usage of petrol and diesel vehicles and buy electric vehicles or anything else that does not require imported fuel. The increased price of fuel can be the best signal for consumers to make this choice of shifting their vehicles’ source of energy. Similarly, even for power generation, an increased cost of fuel can act as a signal for the electricity suppliers to consider moving away from too much reliance of fuel to other alternative (renewable) sources of electricity generation.

Secondly, increased price of foreign currency encourages more exports and foreign currency earning businesses to start-up in Sri Lanka as an exporting businesses could earn higher return in after conversion into rupees. Over the course of time, this would encourage entrepreneurs to set up exporting business. Additionally, the labour force will also acquire more skills required in the export-oriented business fields and ultimately increasing Sri Lanka’s export potential.

Thirdly, increased price of foreign currency can also attract more foreign direct investments into the country. As the foreign companies can benefit from cheaper factors of production such as labour and locally sourced materials.

Hence, an undistorted market would have done a far better job in achieving the Government’s objectives of encouraging exports, foreign investments, even import substitution and encouraging local production compared to any government policy or costly incentives.

Why State intervention in the economy should be minimised?

Firstly, modern economies are highly complex. A short-sighted decision only focusing on one sector, or a set of people can have unintended consequences throughout the economy. This is evident in the models that economists use, which generally assume everything outside the models remain the same — Ceteris Paribus.

Secondly, economies are more dynamic now and the future is highly unpredictable. The future is full of all kinds of shocks such as technological disruptions, geopolitical tensions, global pandemics and climate crisis. The world is much more connected now and it is extremely difficult for a country to be unaffected by these events. Hence, a proper intervention requires carefully assessing all these events, which is overwhelmingly impossible for even the best economist or highly advanced AI to analyse. Whereas the markets consisting of firms and individuals that are decentralised can adapt to the situation in real time and sort out the resource allocation in a better manner.

Above all, a problem specifically detrimental to Sri Lanka is its political system. The way the political system is designed incentivises the government to always please its citizens. Citizens usually cannot be expected to have the knowledge of the long-term implications to the economy. Therefore, to please the citizens in the short-term, long-term goals are jeopardised by the state. Anyone who wants to bring in hard reforms to liberalise the markets are usually elected out and only the ones that intervene in the markets to provide short term relief is voted in. Hence, incentivising elected officials to distort the market.

The way forward

Firstly, in reforming the political system, it is important to agree on rules that will not be broken whatsoever. This can be achieved through constitutional amendments, with the agreement of all parties to bring in some ground rules for the politicians and public to reform the political system. A rule to prevent the distortions in the foreign exchange market can be to set limits on the amount of foreign debt that can be borrowed such as; maintain the nominal value of debt at current values. Hence, gradually reduce the foreign debt share — because paying off all debt at once, with dollars purchased in the market, can only unnecessarily and in unnatural ways distort the market further — and increase the exchange rate. But rather have a policy of strictly not increasing the nominal value of debt.

Further, other rules also need to be brought into place to control state interventions such as limiting fiscal expansion and prohibit financing state owned enterprises. This is important because the distortions in the other markets also need to be removed for the market to function freely in the foreign exchange market. For example; letting the free market decide the exchange rate but subsiding the fuel prices will only jeopardise the forex markets further. Because in this case, the prices of fuel will remain the same and the consumer will not adjust their demand in response.

More importantly, public conception should be reformed. In a way it is the people that have given the steering wheel of the economy to the blind man (Government) by asking the State to intervene in the market to enhance their economic wellbeing. However, the people need to understand more economic prosperity can only be achieved if the State does not do anything. Hence, the citizens need to value the Government’s choice of doing nothing in the market.

In the case of the foreign exchange market, the public need to stop blaming the Government for the depreciation of the rupee and not to pressurise the incumbent government to control the exchange rate. Rather, the public need to form expectations that the rupee will depreciate every year by a certain amount. The expected amount of depreciation will usually be the inflation differential between Sri Lanka and its trading partners — past data suggests 5%.

Finally, in a country like Sri Lanka where the competence of the state is highly questionable, even the distortion of the market for other genuine concerns of market failures and to enhance social equity should be done in a cautious manner. A solid independent economic analysis needs to be performed before every intervention. This analysis should prove that the resulting distortions can enhance the total welfare rather than curtail it. The policy also needs to be implemented after a wider discussion among the stakeholders. When in conflicting views on policy consequences, it is always better to let the market decide than distorting it.

Footnotes:

iDepartment of Fiscal Policy Medium Term Debt Strategy 2019 (publicfinance.lk)

iiDecline in government revenue for 2020 (publicfinance.lk)

iiiIncorrect accounting measure understates significant increase in government expenditure in 2020 (publicfinance.lk)

ivTable 2.3.3, Page 36, Public Report on the 2022 Budget: Assessment of the Fiscal, Financial and Economic Assumptions used in the Budget Estimates (veriteresearch.org)

vThe Government Has to Repay Yearly an Average of USD 4.4 BN Foreign Debt from 2021 Onwards (publicfinance.lk)

viIsard, Peter, Faruqee, Hameed, Kincaid, G. Russell and Fetherston, Martin. (2001). ‘Methodology for Current Account and Exchange Rate Assessments.’, International Monetary Fund Occasional Paper no. 209 (December)

viiCharting A Path for Debt Sustainability in Sri Lanka (veriteresearch.org)