Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Thursday, 5 August 2021 00:08 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

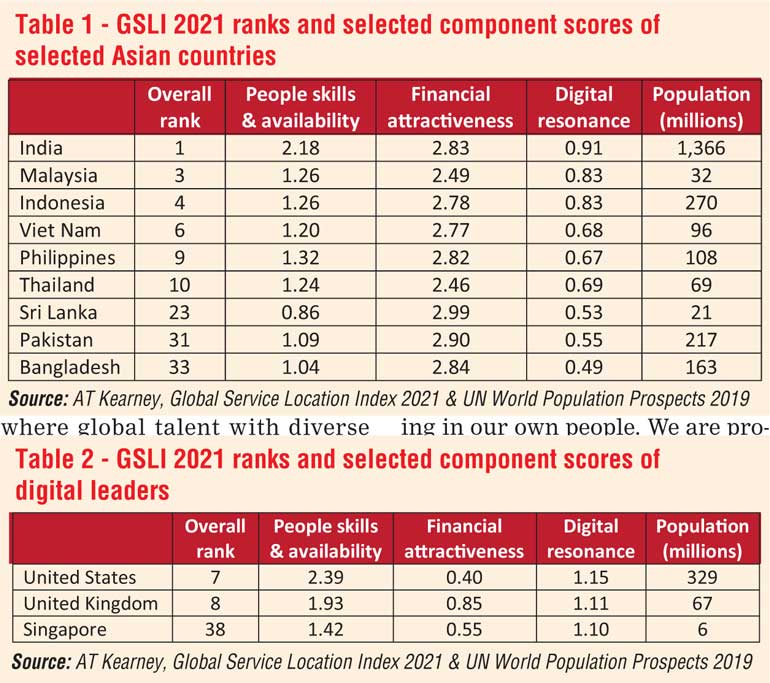

Last week, I wrote of the near certainty of Sri Lanka falling out of the Top 25 of AT Kearney’s Global Service Location Index when it is recalibrated to significantly reduce the weight given to financial attractiveness, or low cost. Sri Lanka was in the Top 25 primarily because we were cheap. Our weaknesses were the quantity and quality of the work force.

attractiveness, or low cost. Sri Lanka was in the Top 25 primarily because we were cheap. Our weaknesses were the quantity and quality of the work force.

Table 1 shows Sri Lanka ahead of Pakistan and Bangladesh in the overall ranking, but behind both countries in People Skills and Availability (which could be influenced by their large population sizes and resultant large pool of those with IT skills); and ahead of only Bangladesh only in Digital Resonance. Of course, it is the leader in terms of Financial Attractiveness (currently 35% weighting), but this will mean little from next year when the weights are recalibrated.

AT Kearney had introduced a new component worth 15% called digital resonance to reflect strengths in digital skills of the labour force, digital outputs, the amount of corporate activity, legal protections of intellectual property, and other elements of business activity. Because of their judgment that quality is becoming more important, the weight given to digital resonance will be raised from 15% to 60 and the weights of financial attractiveness and people skills and availability lowered to 10 each. All peer countries will decline in ranking with only India, Malaysia, and Indonesia likely to remain in the Top 25.

What can be done

How can the laggards get back in the running? Looking at the new Top Three: the United States, UK and Singapore, may yield insights.

On digital resonance, Singapore is almost even with the UK and close to the US. Sri Lanka is leagues behind. Since this component is to be given a high weight, no country can afford to ignore it. Most effort is required to enhance digital skills, which is the biggest element within digital resonance, and which also has a bearing on people skills and availability.

But this will not be easy in the short term. Singapore’s plans for a creative economy were laid as long ago as in 2006. I quoted from that budget speech when commenting on the five hubs proposals put forward by President Mahinda Rajapaksa in 2010:

“Singapore must be a place where global talent with diverse backgrounds and cultures want to live, work and play. George Lucas set up Lucasfilms’ first and only studio outside US in Singapore partly because of our cosmopolitan appeal. When the studio opened in October last year, its first batch of 35 animators came from 19 nations, including Panama and Ecuador. We will continue to develop new attractions such as the Integrated Resorts and the Singapore Flyer, to make ours an interesting, lively and fun ‘City-in-a-Garden’. Besides attracting talent, we are also investing in our own people. We are providing our students with opportunities, from the primary up to tertiary level. Our schools are striving to develop critical thinking skills and creativity in our students.”

A recent news report showed how these ideas had been implemented. A master plan is being implemented for the 50-hectare Punggol Digital District since 2018. The Singapore Institute of Technology that commenced operations in 2009 will have 10,000 students and 500 academic staff in the District. Just this month, four international companies confirmed their plans to establish facilities in the Digital District, that will create about 2,000 jobs ranging from data analysts and solution engineers to artificial intelligence and blockchain developers. A cyber security firm is moving in.

implemented for the 50-hectare Punggol Digital District since 2018. The Singapore Institute of Technology that commenced operations in 2009 will have 10,000 students and 500 academic staff in the District. Just this month, four international companies confirmed their plans to establish facilities in the Digital District, that will create about 2,000 jobs ranging from data analysts and solution engineers to artificial intelligence and blockchain developers. A cyber security firm is moving in.

How will a country with a population below six million, come up with enough specialised personnel to fill 2,000 positions in a range of specialisations? How will it get 500 high-quality academics for a new campus without cannibalising the existing universities? The answer, as stated in the original blueprint, is openness to global talent. If Singapore, with its small population base, chose to rely only on local talent, its People Skills Availability score would most likely be closer to Sri Lanka’s 0.86 score.

The population column was added to the tables to indicate the challenges faced by small countries. Most of our competitors have large youth cohorts from which they can meet the requirements of most companies wishing to set up operations. Small countries like Singapore and Sri Lanka cannot rely solely on local talent. They have to be open to global hiring. Singapore is, and is flourishing. Sri Lanka is not, and is falling off the charts.

I was pilloried for proposing information technology as one of the sectors Sri Lanka would be willing to open up for circumscribed entry by professionals in the early stages of the negotiation of a bilateral trade agreement with India. The protectionists won. Sri Lanka is attracting low-priced BPM business and is becoming less attractive by the day. Singapore is attracting the cyber security and data analytics firms and jobs. The consequences of our choices are becoming clear.