Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Wednesday, 24 July 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A number of very important people called to thank me for inviting them to the very popular presentation by Dr. Howard Nicholas. It was held on 18 July at the Postgraduate Institute of Management (PIM) auditorium. The title of the presentation was ‘Sri Lanka’s Development Challenges and Lessons from Vietnam’.

The credit should, however, go to the PIMA (Postgraduate Institute Alumni Association) and Professor Ajantha Dharmasiri, Director of PIM, who steered the panel discussion comprising Dr. W.A. Wijewardena, Dr. Nishan de Mel and myself.

A few friends however asked me what happened. “You were not your normal self, you were hardly audible,” they said. Excuses are of little value after causing disappointment. I had to however say that I suffered a migraine attack a few minutes before going up to speak. This note, I hope, will compensate for that lapse.

Howard’s presentation basically focused on four areas: the theory of comparative advantage, the manufacturing sector, role of government and dynamism of the private sector.

Comparative advantage

If we stick to the theory of comparative advantage we would be still relying on the production of tea, rubber and coconut as well as gems and spices, bequeathed from the colonial administration. Manufactures based on cheap unskilled labour was added on to the list later. The thinking among our policy makers started changing when the traditional products ran into trouble both with regard to domestic output and markets.

In the period 1970-’76 we attempted to break away from this dependence by introducing import substitution policies. It was rather late in the day when we had realised that we cannot go too far, and tried to adopt outward looking policies with the change of government in 1977.

We had to, however, wait till 1989 to take things forward by embarking on garment manufacture. We are always too late to meet the challenges of time. Now we have to think of new production structures to meet the challenges of changing international demand and competition from other countries, particularly, Thailand, Vietnam and Bangladesh.

Manufactures

Howard’s point about manufactures is very valid. No country could go on with agriculture, infrastructure and services, since at the end of the day they do not cater adequately to consumer demand. He mentioned how Vietnam benefitted by promoting manufactures.

I could, however, point to a far more striking example. I could say that the Soviet economy collapsed, bringing down the whole communist edifice, due basically to a gross neglect of the manufacturing sector.

The Soviet economy thrived, when it was doing coal mining, oil production and heavy machinery production related to the defence industry. With rising personal incomes the Soviet regime had to cater to increasing demand for manufactured goods. Imports were drastically restricted and whatever was domestically required had to be produced by the local production system based on public enterprises which were grossly inefficient.

The planning system could not cope with the rapid changes in the consumer markets. Apart from poor quality products by international standards, there were frequent shortages of goods existing side by side with oversupply. In a competitive system based on private enterprise producers follow market trends. Those enterprises that do not comply fall by the way side. They close down. This does not happen in a public enterprise system.

Howard’s point about too much reliance on the service sector is quite correct. He does not discard the importance of infrastructure and the financial services. He also agreed with the role tourism could play in a country such as ours. But he cautioned against too much reliance on the tourism sector. He said it would be even dangerous, due to vicissitudes, if there is no fall-back position, which is often provided by the manufacturing sector.

The most powerful driving force of the manufacturing sector is its capacity to overcome the limitations of the domestic market by catering to international demand.

The private sector

Howard was confident that our private sector is quite capable of meeting the challenges of development if the domestic policy and institutional environment are conducive. This view is supported by the fact that many of our companies are doing well internationally. One of the most important factors that determine their capability in the domestic market and eventually export capability is the ‘Ease of Doing Business’ environment.

The good news is that Sri Lanka has moved up 11 notches in the World Bank Ease of Doing Business Index being ranked 100 among 190 countries. This position can improve if some of the constraints relating to regulation of property, enforcement of contract and tax payments could be improved.

Role of government

Howard debunked the myth that governments of developed countries do not support business entities. In fact they work hand in glove. While pontificating against monopoly practices and preaching neo-liberalism to developing countries, the US government, for instance, does just the opposite.

Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman once lamented that “business corporations in general are not defenders of free enterprise. On the contrary, they are one of the chief sources of danger.”

They love regulations that erect barriers to entry to their competitors. Philip Morris aggressively lobbies for federal regulations of tobacco products, MacDonald’s, Starbucks and Kraft have spent millions of dollars lobbying for food safety regulations; and all this, while spending billions of dollars of taxpayers’ money to support small enterprise.

Public-Private Partnership

What should be the role of government in Sri Lanka and what could the private sector do to influence it? Howard advocated a more dynamic role for the private sector in the government’s decision making and implementing process. But for this, there must be first an attitudinal change in the government and the bureaucracy. This must be backed by a an institutional framework, which facilitates a systematic dialogue, going beyond the ad hoc arrangements of today, which are mostly media shows.

The private sector too must be prepared to take up the challenge. It must be properly represented. The best method is for the private sector to be included in the discourse with government through representatives of the various business chambers, rather than through selected individuals, which should be restricted to eminent academics and researchers. Representation through chambers gives an opportunity to reflect a collective view.

The private sector representatives too must be prepared to take a holistic view of the issues at hand. The economy is composed of various segments (sectors and sub-sectors) which are symbiotically linked. They must work in harmony. Ad hoc piecemeal interventions, therefore, could be not only counterproductive but also harmful.

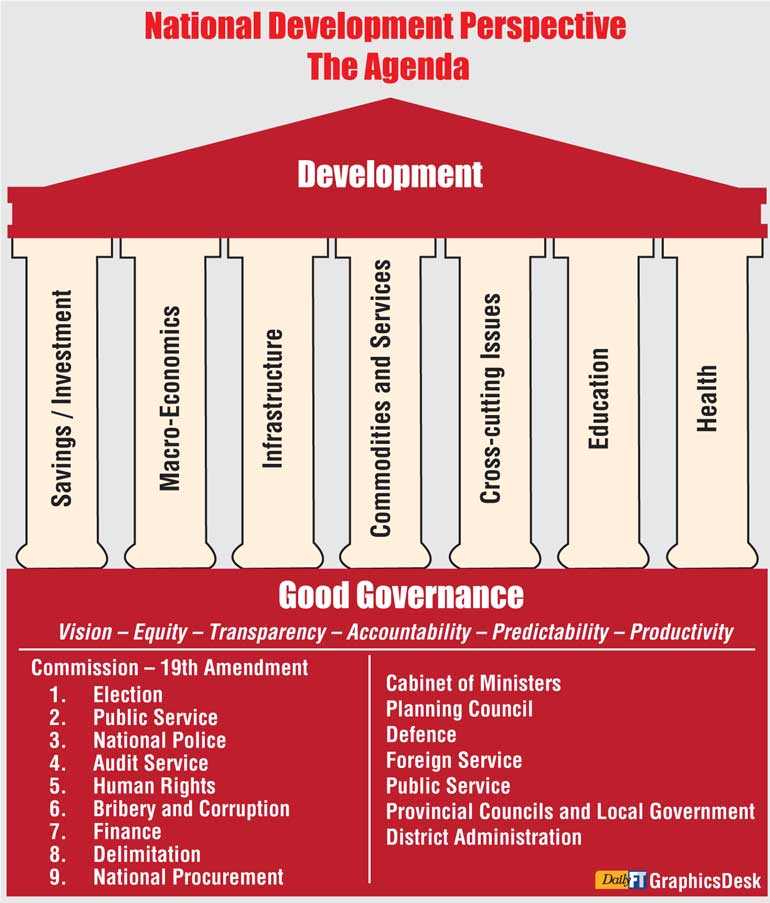

Good governance

The diagram which has been developed for teaching purposes at the PIM gives a holistic view of the development process and the segments that need to be harmonised. At the roof top is development that we want to ultimately achieve. But development means different things to different people. It must be defined as a collective concept and identified in the form of key performance indicators which reflect the ultimate objectives, outcomes or impact to be achieved.

The pillars represent the sectors or segments that must work in harmony. They are all inter-related and cannot be treated in isolation. Savings and investment affect all sectors. FDI, for instance, affects the performance of all sectors, including cross cutting issues that relate to environment, gender and poverty alleviation programs.

The foundation stone is good governance, beyond rhetoric, going beyond the ethical and moral connotations, operating as technical imperatives of development.

The diagram indicates the legal and institutional framework for good governance. The most important institution is the cabinet of ministers. A large and disjointed cabinet structure is fundamentally disruptive. The cabinet structure must be arranged on the sectoral principle. Vietnam has only 26 ministers to serve a population of 96 million and Sri Lanka, at the last count had 47 to serve a population of 21 million.

The Cabinet must be served by a highly effective and efficient administrative structure. Public servants have been the custodians of good governance. To play that role again they must not only be subservient to the whims and fancies of their political masters but also knowledgeable and confident.

Vietnam has invested large sums of money to train and motivate their public servants, who too suffered in the past serving under a highly bureaucratic regime. Vietnam today sends some of its best officers to developed countries for training and exposure.