Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Friday, 11 October 2019 00:15 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In the last 10 years global HR thought leaders have created a very powerful human capital view, that if you invest in your own education you’ll get returns in a better job and better income, and also that educated people stand a better chance of getting a job than those who don’t go to university.

In the last 10 years global HR thought leaders have created a very powerful human capital view, that if you invest in your own education you’ll get returns in a better job and better income, and also that educated people stand a better chance of getting a job than those who don’t go to university.

Next, at a political level we had a very powerful human rights argument that education is a fundamental right, and therefore we need to do something in developing countries about getting children into schooling.

Then there was the negative view that higher education was for the wealthy, the elite, and that it was very expensive. So many organisations questioned why you would put money into higher education when primary education was very much more important, and for the same amount of money could reach many more people.

Then a question that is often asked is, what is the real connection between education, innovation and economic development? If you take a simple human capital view of economic development, it’s fairly straightforward: if you invest in people’s education, then incomes will develop. But that presupposes that people are going to get jobs and that there’s something that’s actually driving the development.

The more important question is, how do jobs actually get created? How do countries take on new technologies and become effective producers? In this kind of argument it’s not just thinking about supplying the education, it’s saying that knowing where the possibilities for an economy to specialise and develop are going to be important in thinking about how economic development takes place.

It is not a simple universal model, where invest more in education, positive things will come out – but if you take a particular country, you can look at what capacity it already has in terms of education and training systems, its industrial system, the existing network between firms and the capacity of the state to support them, but also what positions it could possibly take up within the global system.

Focused investments

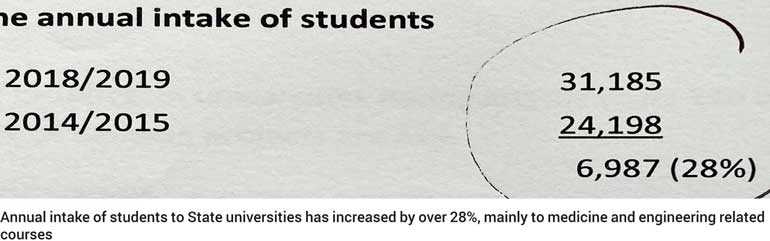

Therefore Sri Lanka needs to look at a range of different factors rather than just invest more and more into education hoping the market will take care of the mismatch between the quality of high-skilled labour demanded and supplied and also provide the required new jobs for those coming out of the education system.

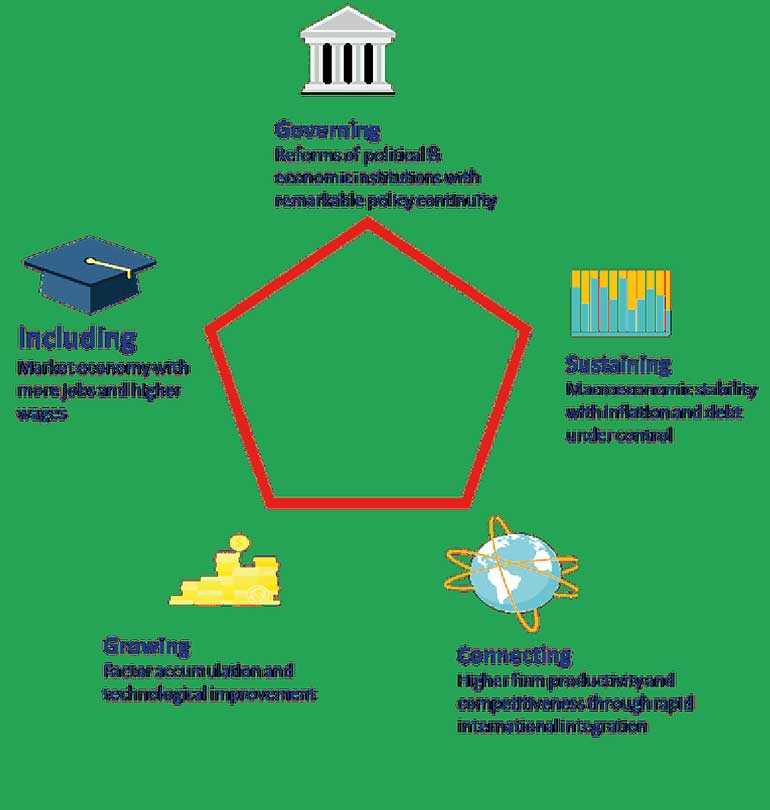

There is no doubt higher education is a key element of developing new innovations and thereby help GDP growth to accelerate. But another important role of higher education is around developing professionals. Professionals play a key role in picture: key factors critical for our future success meeting health, education, agricultural and water goals: engineers, doctors, nurses, teachers – the whole range of professionals who are vital for development. Therefore producing the right professionals for our future success, is key.

Also there is a need for greater competition between education providers in a marketplace to bring about higher and higher quality of content for a lower and lower overall cost. Given that investing in education and leaving it to the markets will only do so much. We need a new way of looking at the relationship between higher education, economic development and employment.

The widely adopted human capital view is that higher education increases skill and knowledge and results in higher income.

In practice however, geography, sectors, available skills and education systems and networks of companies, value chains, employment patterns and policy frameworks associated with each sector are equally important factors that are often ignored.

We have spent decade upon decade surrounded by a system that is, for all practical purposes, a “one-size-fits-all” system. Because quality improvements at that level affects employment creation and also for those young highly -skilled workers to get “better paying jobs”.

The education to employment continuum and the requirement for compulsory education of 13 years and the required Labour and education reforms need to kick in fast to ensure our workforce is future ready and get us out of the middle income trap (MIT – the middle-income trap refers to the phenomenon where rapidly growing economies stagnate at middle-income levels and fail to transition into a high-income economy) and for the creation and professionalisation of talent pools for specific industries.

(The writer is a thought leader.)