Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Wednesday, 18 May 2022 00:28 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Government, at last, decided to seek the support of the IMF after two years of waiting. IMF responded well as usual and agreed to carry out its duty as the “lender of last resort”. Now, politicians admit that the current crisis could have been avoided if the Government had acted wisely. But unfortunately, it did not happen either due to ignorance or stubbornness of those responsible, political leadership and advisors.

responded well as usual and agreed to carry out its duty as the “lender of last resort”. Now, politicians admit that the current crisis could have been avoided if the Government had acted wisely. But unfortunately, it did not happen either due to ignorance or stubbornness of those responsible, political leadership and advisors.

As the Central Bank took the first step by approaching IMF, now it is time to understand what the IMF program delivers, the role of the Government in implementing it successfully, and the gap between the work of IMF and what is left to the Government in terms of policy reforms. The success of such reforms heavily depends on the commitment of the Government to undertake policy reforms effectively in a timely manner. The failure to do so will have unfavourable results, as evidenced in countries where the IMF bailout programs failed.

IMF bailouts

IMF was established in 1944 to promote international financial stability and support countries facing short-term financial emergencies. In return, the recipient countries were expected to undertake some policy reforms, which are commonly called “Conditionalities.” IMF financially assisted over 100 countries with over $ 1 trillion during the last 70 years. IMF packages generally have 3 components: (a) Financial package, (b) Structural reforms, and (c) Macroeconomic reforms. Some research shows that the size of the financial package depends on the nature of the recipient country’s relationship with the major creditors of the IMF, including the US.

Conditionality in terms of structural and macroeconomic reforms in exchange for such assistance usually falls into 6 major categories (a) Debt sustainability, (b) Fiscal policy consolidation, (c) Rationalisation of monetary policy, (d) Removal of exchange rate controls, (e) Trade and investment reforms, and (f) deregulation and public sector reforms. Some of these are already mentioned in the recent IMF reports and statements on Sri Lanka.

Successful stories

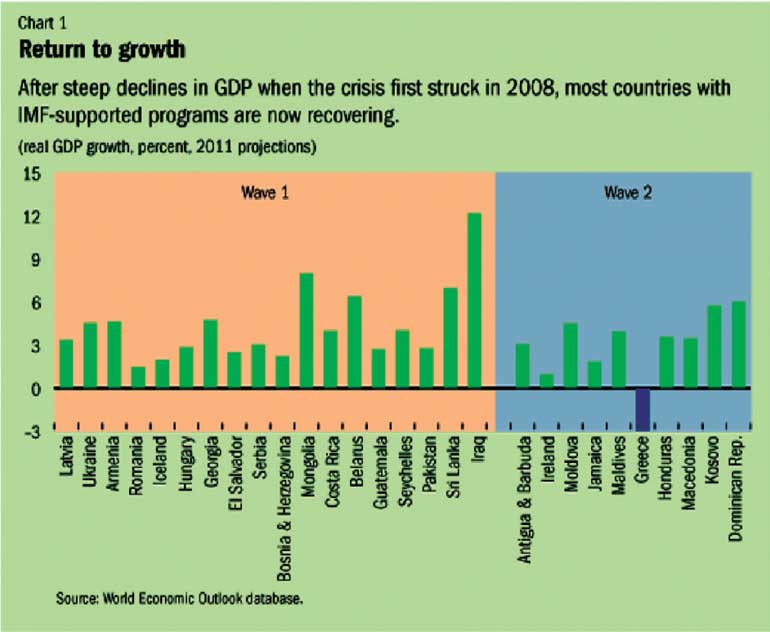

Proponents of IMF programs claim that IMF provides liquidity and spearheads economic reforms, which help prevent more extreme financial adversities. One study based on 69 bailouts from 1973 to 1980 pointed out the positive impact of bailouts on the balance of payments and inflation1. As shown by analysts, the success stories were Mexico, India, Tunisia, Serbia, Jordan, Egypt, and Kenya. However, the processes of bailouts were not always smooth and straightforward. They met with hurdles, setbacks, and challenges. Chart 1 shows the recovery path of some countries that are recipients of bailouts during the last financial crisis.

Unsuccessful stories

Some argue that IMF is too interventionist in domestic affairs. On the other hand, some claims what they deliver is too little. IMF is also accused of promoting neo-liberal policies such as privatisation and liberalisation. The common belief is that the bailout designs overlook the recipient countries’ unique economic, social, and cultural conditions. The studies also doubted the contribution of such programs to financial recovery and stability, which was attributed amongst others to the short-term nature of such assistance. Nobel laureate Joseph Stieglitz is of the opinion that though IMF programs worked for some Latin American countries, such programs are not appropriate for everybody else. It was claimed that some Asian countries were made worse off because the IMF treated the Asian crisis in 1997 as any other emergency, insisted on structural reforms, and asked the countries to cut expenditure, which deepened the economic slowdown. For example, the unemployment rate in South Korea increased from 3% to 10%. Poverty in Indonesia rose from 11% to 50%, and GDP declined. In Europe, Greece failed. In the case of Greece, the IMF austerity measures were found to be too stringent, resulting in defaulting on the IMF loans of $ 1.5 billion. Fortunately, the European Central Bank extended financial support and rescued the country from the crisis. However, developing countries, including Sri Lanka, do not have such a saviour.

In another research based on 1,300 studies of bailouts from 1970 to 2015, researchers found no conclusive evidence of the success of bailouts. However, the possibility of moral hazard when governments use more aggressive economic reforms to get more financial support from the IMF was found. Structural reforms in exchange for financial aid are claimed to be not a good long-term strategy. Malaysia rejected IMF intervention and resorted to domestic policy reforms, including capital account restrictions.

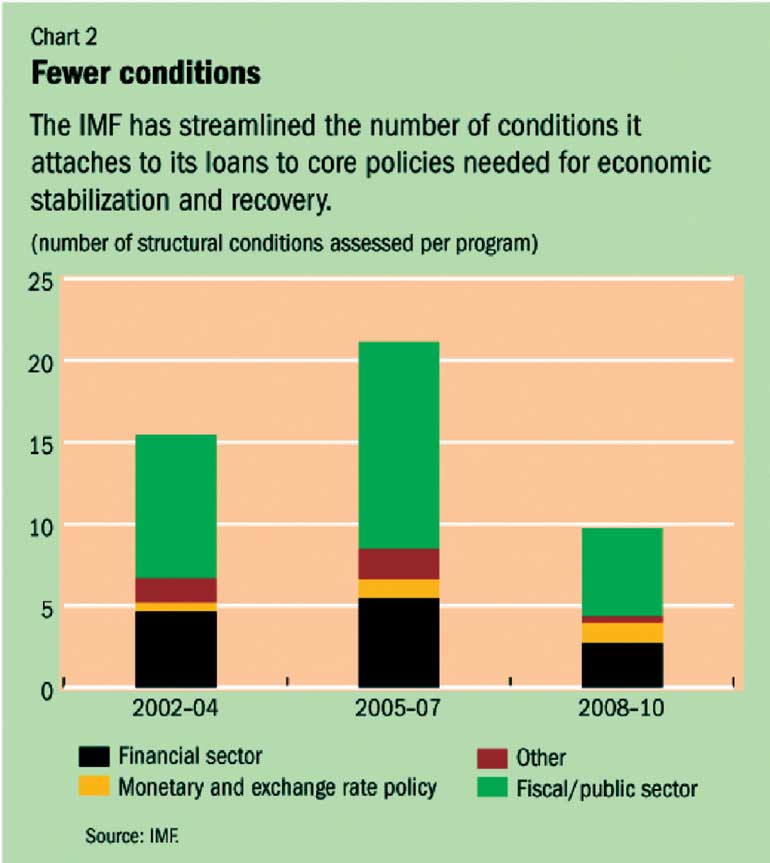

The major criticism level against the IMF is harsh austerity measures pressuring recipient countries to reduce expenditure too fast, endangering the whole development process leading to massive job losses, and further aggravating recession in already weak economies. Though there is a truth in this claim in the early years of IMF operations, it is evident that the IMF itself changed its approach to financial assistance with less stringent prescriptions, as shown in Chart 2.

Though there are many country studies on the impact of IMF support programs, no consensus was found among researchers regarding the reasons for the failure of such programs. The widely suggested reasons include the inappropriate designs of the packages, political instability, weak macroeconomic fundamentals, lack of government commitment, and most importantly, lack of effective enforcement of reforms. Further, it was found that the level of corruption, policy reversals, and the gap between the amount of reserves and short-term debt obligations are other factors for the withdrawal of such assistance and policy failures.

Sri Lankan experience

Sri Lanka used IMF bailouts 16 times from 1965 to 2019 – agreed with Rs. 4.4 billion and drawn Rs. 3.5 billion. At present, an IMF offer for Rapid Financing Instrument was already ruled out, and the Government is preparing for a general fund facility as in the past. Though it is too early to know the exact amount of financial support and the time framework, based on IMF assistance in Sri Lanka and other developing countries, one can presume that Sri Lanka would receive around Rs. 3 billion to be utilised over three years. The negotiation process will take at least six months.

On the issue of the impact of IMF programs in Sri Lanka, there are diverse views, as was observed in other developing countries. Some are entirely against IMF interventions because of the harsh conditions usually associated with such assistance and the potential loss of autonomy and sovereign rights to manage the economy independently. Some like the economic policy discipline, stability, and credibility that IMF brings to the country. The most comprehensive evidence-based study on the impact of IMF assistance in Sri Lanka was conducted by Professor Prema-Chandra Athukorala of the Australian National University. He analysed data from 1965 to 2019, used quantitative methods, and found that average economic growth during the IMF-supported period was 1.26% higher than that of the non-IMF-supported period. This percentage would become 1.45 if only the fully disbursed (Sri Lanka received the agreed amount fully from IMF) years were considered. The summary of findings was published in the Daily FT in 3 parts. Professor Athukorala concludes his investigation by saying: “There is convincing evidence that the growth rate of the economy was significantly higher during the years of fully-implemented IMF programs. However, the long-standing fundamental macroeconomic disequilibria of the country has persisted despite the repetitive reliance on IMF programs. This simply reflects policy failures of the country to use the breathing space provided by the programs to undertake the required structural adjustment reforms: the ‘repetitive client status’ of the country does not, therefore, make a case for rejecting IMF support”.

Conclusion on IMF assistance

The IMF assistance is not free from criticism. However, the reality is that IMF has become the lender of last resort as there is no other alternative to match what it offers. Since it was established, over 100 countries have sought financial support, some multiple times. IMF grants low-cost, larger and long-term loans. Partnering with IMF provides guarantee, credibility, and confidence to the rest of the creditors so that restructuring of external debt becomes much more manageable. Nevertheless, Sri Lankan policymakers need to remember that IMF assistance is only a partial solution to the current crisis. Much more needs to be done by the Government.

Based on the past experience of IMF interventions elsewhere and in Sri Lanka, the author believes that IMF support is critically essential for the economic recovery from the current crisis. It can carry out its duty at least moderately. It is hoped that the Central Bank is well-aware of both advantages and disadvantages of IMF assistance, success factors, and reasons for failures. It should negotiate the package considering ground realities concerning the country’s economic, social, and cultural conditions. Sri Lanka has a right to design an appropriate package in collaboration with IMF. Central Bank is also expected to implement the program successfully without being subject to political interventions.

Central Bank cannot deliver miracles

Since the Government entered into a discussion with the IMF, everybody’s attention is turned to Central Bank, which is expected to deliver solutions to all the country’s problems. This is a false hope, and Central Bank can only carry out part of the national recovery plan, at most 25%. The Central Bank will engage with the IMF and look after macroeconomic issues and the management of reserves. Though the mismanagement of these policies is the immediate cause of the current situation, the magnitude of the crisis is much larger and more profound, requiring immediate actions parallel to the work carried out by Central Bank. For instance, the Ministry of Finance should get involved with fiscal policy consolidation in collaboration with line ministries, including the Ministry of Trade. Fiscal consolidation involves the temporary suspension of capital expenditure (building roads, grounds, ports, towers, etc.), undertaking tax reforms, and using savings for essential services.

In addition, resources need to be allocated to deal with hunger and poverty, basic services such as health and education, and essential utilities such as electricity. Special attention will have to be paid to society’s vulnerable and disadvantaged segments. All these are temporary solutions to the crisis. Sri Lanka needs a comprehensive, time-bound, results-oriented plan to achieve inclusive and sustainable growth and prosperity for all in the long run.

Given that the IMF assistance is only a partial solution to the multiple crises the country is grappling with, the following actions are urgently required to supplement the IMF program.

Footnote:

1 See Larry Li et.al Journal of Policy Modeling, Volume 37, Issue 6, November–December 2015, for a comprehensive review of studies

(Dr. Ravi Ratnayake, former United Nations Director of Trade and Investment and the Chief Economist for the Asia-Pacific Region, has been an economic advisor to many developing countries in Asia. The writer can be contacted at [email protected].)