Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Friday, 22 October 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

On 1 October, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) announced a policy decision to buy-back some of the International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs) issued by the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL). These bonds had been selling at heavily discounted prices in the secondary market for sovereign bonds. Ten days later, on 10 October, the CBSL made a widely-reported public announcement cancelling this policy decision (https://www.dailymirror.lk/business-news/Central-Bank-shelves-plans-to-buy-back-maturing-ISBs/273-222337.)

selling at heavily discounted prices in the secondary market for sovereign bonds. Ten days later, on 10 October, the CBSL made a widely-reported public announcement cancelling this policy decision (https://www.dailymirror.lk/business-news/Central-Bank-shelves-plans-to-buy-back-maturing-ISBs/273-222337.)

The purpose of this article is to examine the reasons for making and almost immediately withdrawing the policy decision. As the writer is not privileged to have any insider information, the analysis in this article is based on the (limited) information contained in the press release of CBASL, and the known realities of the bond market. In other words, this article examines the decisions of the CBSL while informing the readers how the ISB market works. As many readers may not know the basics of ISBs, the article begins with a brief introduction to ISBs.

An introduction to ISBs

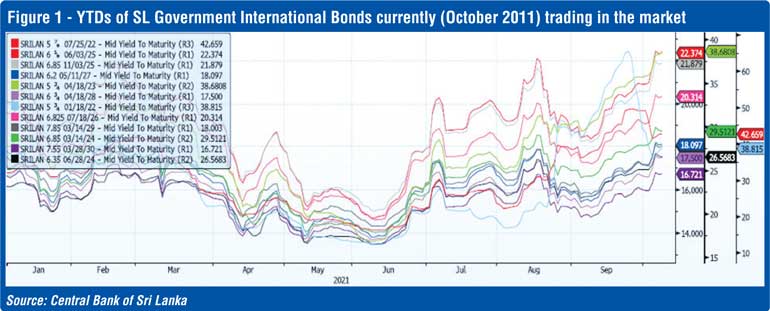

The GOSL, has already made several ‘issues’ of US$ denominated bonds in the international capital markets and raised funds (borrowed money in US$). These bonds carry coupon interest payments, paid bi-annually by GOSL (the issuer). The bonds must be settled (paid-off) on their maturity. At present, GOSL has 12 issues of IBSs to be paid-off on varying dates in the future (See, Figure 1). Until these bonds are settled, the holders (investors/owners) can, if they wish, sell their bonds in the secondary market at the going price. If sold, the new owner will continue to receive, as promised by GOSL, the interest payments bi-annually and the principal (Face Value of the bond) on the date the bond matures.

The bond investors (holders) make their investing/holding/selling decisions based on the return (gain) they can expect from a particular bond. If an investor holds on to their bonds until its maturity without selling in the secondary market, the returns he/she will receive are the coupon interest (twice a year) and the return of the capital (face value) at the maturity. Because rational investors are always looking for ways to maintain/increase their wealth, they keep an eye on the secondary market and make decisions and take actions to minimise possible losses or maximise possible gains.

For example, if the current market price of the bond they hold is lower than its face value they will get concerned and may consider the option of selling their bonds at the prevailing market price in the secondary market. After careful consideration of the available options (opportunity set) some would sell, some would hang on to the bonds thinking that the prices will recover, and some would continue to hold the bond on the belief that GOSL will not default on interest or principal.

In addition to the above, one needs to understand the concept of yield to maturity of bonds (YTM). YTM is the return (yield) the holder of the bond can expect to receive during the remaining time from now onward to the bond’s maturity given its current market price. The YTM is computed based on several factors including bond related characteristics such as current market price (P), face value (FV), coupon interest rate per annum adjusted for frequency (CI), time to maturity from now (T). These characteristics can be used to estimate the underlying rate of return of the bond under reasonable assumptions.

This rate of return is called YTM (in the familiar language of project evaluation, IRR). YTM reflects the current required rate of return of the ‘market’ from the ISB. (YTM is just a mathematical outcome when we solve a bond formula using the observable market price and known values of the other three variables of the bond: FV, CI, T). YTM is one of the simple measures market participants use when making investment decisions (buy/hold/sell decisions) in the ISB market. A basic rule to remember is “higher the YTM the lower the current market price of a bond, lower the YTM higher the current market price of a bond”.

SL Govt. International Bonds currently trading in market

GOSL has (owes) about $ 13 billion worth of outstanding ISBs. These issuances were made for different periods with varying maturity dates, and carry different coupon rates, and have different YTDs (See, Figure 1).

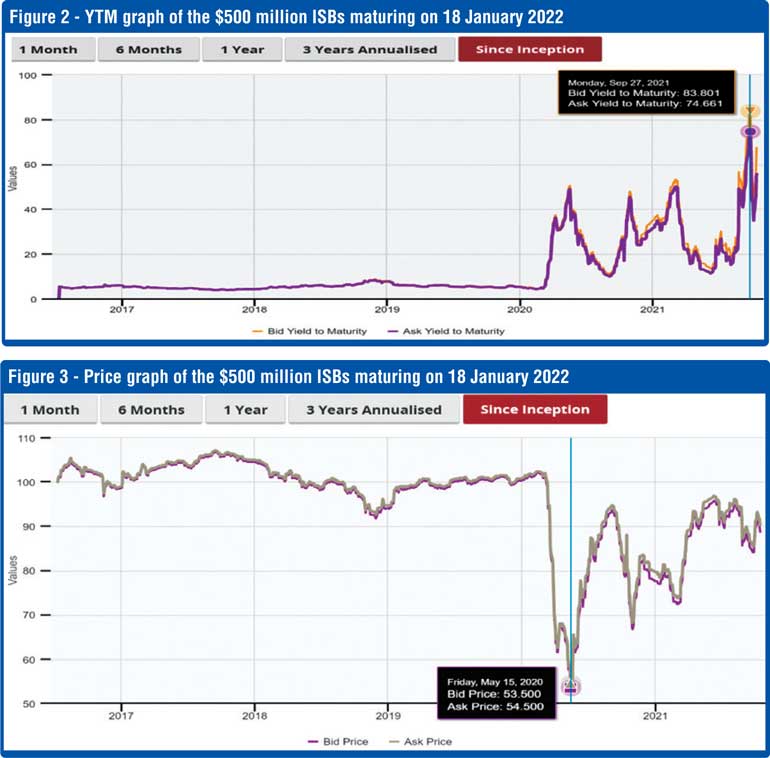

For example, the ISB with a coupon interest rate of 5.75% per annum, maturing on 18 January 2022, was having a YTM of 38.815%. (This rate keeps fluctuating day by day depending on the market sentiment. It went as high as 70% on some days, see Figure 2). This means, at the time this graph was extracted, the investors needed around 39% return per annum compared with its coupon rate of 5.75%. That is, the investors’ required/expected rate of return (38.815%) was much higher than its coupon interest rate (5.75%). Therefore, the market price of these bonds was lower than their face value. They were being sold at a large discount. For example, the ISB maturing on 18 January 2022 was sold at USD 93 (approx.) at the time the graph was extracted. (As the price was not given in the CBSLs’ announcement, this price was computed by the writer using the bond pricing formula discussed above).

As you will note, the YTM of the bond has fluctuated between 6% and 83% (approx.) between its inception in 2016 and October 14, 2021. The sharp rise in yield on 27 September 2021 was in response to investor perception on the impending extreme event of default by the GOSL.

The price of the bond has fluctuated between $105 and $53.50 (approx.) between its inception in 2016 and 14 October 2021. The lowest bid price was $53.50 on 15 May 2020.

After the initial decline in May 2020, the market has reacted positively with mixed results, but the trend is positive since 15 May 2020. The market must have sensed that the GOSL’s capacity for payment would improve going forward. However, we need to see what is happening to the other maturities as near maturity bonds tend to converge to the par value as the case with this bond maturing on 18 January 2022.

CBSL’s policy decision to buy-back ISBs

As shown above, the GOSL bonds were selling in the market at discounted prices. This was because of the sense of the market that the Government would not be able to settle them on due dates as promised. Having observed these prices, CBSL seem to have thought that this was a good opportunity to buy-back some of these bonds at depressed market prices (rather than paying $100 + half year interest of $2.875) at the maturity. Because deeply discounted market prices of all the outstanding issuances (batches) of bonds, CBSL formulated a policy to reduce the total value of bonds to 10% of GDP (from the current level of 14% approx.) during the next three years and announced it with its Road Map released on 1 October 2021.

This policy was inappropriate and unrealistic because of several obvious reasons:

1. Lack of foreign exchange/external assets to buy-back outstanding ISBs.

2. Even if GOSL can raise external loans, the interest rate to be paid on such loans will not be less than the interest rate it is paying for the ISBs, for example, the interest rate on the bonds maturing on 18 January 2021 is 5.75% per year.

3. CBSL should have understood that managing GOSL’s finances (its huge budget deficit), managing the country’s trade, and balance of payment deficits are at the root of the problems. Getting out of this situation requires ‘managing the finances’ of GOSL. Since there are no realistic plans by GOSL to do so, CBSLs policy of reducing ISBs to 10% of GDP was unrealistic.

4. If at all, CBSL should have thought of ways to win the confidence of the ISB market, so that it could issue new ISBs at least to roll over (refinance) the outstanding ISBs.

5. CSBL has ignored the advantages of having/issuing new ISBs for a developing country such as Sri Lanka (e.g., fixed interest rates, fixed principals). In an environment of rising world inflation ISBs reduce volatility, risk, and provide certainty.

6. Bond financing, unlike borrowing bilateral donors, does not have any hidden strings attached. Another advantage is that Government become subject to the unbiased monitoring and evaluation of the international capital markets. Such monitoring and evaluations will, hopefully, inculcate financial discipline within the Sri Lankan Government.

7. It seems that CBSL did not have a proper understanding of how investors in the ISB market think and behave. Unless the CBSL had planned to engage in a covert (hideous, secretive) operation, the ISB market would have anyway got the information that GOSL was going to buy-back its outstanding IBS before their maturity. This would have increased the price the bonders were willing to offer their bonds for sale. The prevailing discounted prices would reach a price very close to the face value ($100). Hence, there would not have been worthwhile gain for GOSL from the envisaged buybacks.

In summary, it is difficult to figure out how CBASL/Government was going to find foreign exchange to buy back outstanding ISBs. Also, it is hard to see an explicit overarching ‘wealth enhancing’ rationale (e.g., reduction of risks, reduction of costs) for the CBSLs policy decision to reduce ISBs to 10% of the GDP in 3 years.

The reasons given by CBSL for the cancellation of the buy-back initiative:

Ten days after announcing it in its ‘Six-Month Road Map for Ensuring Macroeconomic and Financial System Stability,’ CBSL gave up its plans to buy-back outstanding ISBs. CBSLs press release dated 11 October (see https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/news/isb-maturing-in-2022-quoted-at-discounted-prices) gave the following reasons for its decision. Quote:

Overall, the Central Bank observations on the attempted buy-back initiative are as follows:

Unquote (emphasis by the writer).

Some of the reasons given/observations made by the CBSL are correct or fair. However, some are incorrect or unfounded. The writer has highlighted (in bold letters) reasons/observations which are incorrect/unfounded. Given the limited space available, comments are only about the incorrect or unfounded observations made/reasons given in the CBSL’s press release.

a.“Will not be fair by the large number of ISB holders who wish to hold the ISBs to maturity”.

This an unusual statement/sentiment. The ISB holders who wished to sell their holding at the offered prices (around $ 93), have made a rational decision to do so based on their own opinion. CBASL should not think that it can make a better decision on behalf of the bond holders by not buying their bonds. Neither the bond market nor the share (stock) market is a place for such sentiments.

b.“Therefore, the concerns raised by certain quarters regarding a possible vulnerability in 2022 are clearly not reflected by this investor sentiment.”

This is an unfounded statement. The bond holders who have offered to sell their bonds are willing to forgo 39% (annualised) return they can get for a period of about 100 days. If they do not sell now but keep the bonds until their maturity on 18 January 2022, they can realise this return. In other words, if sold they would forgo the likelihood of receiving the principal $100 (Face Value) and $2.875 (the last half-year interest payment) from GOSL. Why would 5% of the bond holders (owners of 250,000 bond units) want to sell, instead of waiting for 100 days? [(computation: ($500,000,000/100) x 5%=250,000]. It is because these bond holders are afraid that the GOSL would default. This sentiment/opinion of is based on whatever the information they have. The writer agrees that 5% is not a big enough lot to repurchase to implement the CBSL’s policy. However, 5% is a sufficient indicator of what the ISB market thinks in general. Furthermore, no one knows how many more bonds would be offered for sale if the CBSL placed an on-market bid for, say $94 or $95. If the CBSL was serious, it could have gone for an off-market buy-back and either offer a set price for a bond or adopt a process like ‘book-building” to decide the final buying-back price. This could have been done because both on-market and off-market buy-backs are allowed in the bond deed.

c.“Will not yield a successful outcome, given the appetite of ISB holders to hold the GOSL ISBs.”

The reason given for not being able to expect a successful outcome does not sit well with the facts. The balance 95% of the bond holders have not offered their bonds for sale because the price they are likely to get now is less than what they want. They watch the market and notice that even at $93 there are no bids to match it. Technically, that is why the offer remains in the system. As soon as there are sufficient bids at $93, the bonds on offer will get sold. The prospective sellers who might be willing to sell at, say $95 may not have entered their offer in the system yet. It is not that every bond holder who intends to sell at a higher price will always have entered their asking price and wait for a bid. It is likely that most of the remaining bond holders may not have made (entered) their offers because they don’t want to sell at the going prices. Probably, most of the remaining bond holders will sell before the maturity date, even at less than the face value, if the price they can get is significantly higher than the current bid price. Therefore, it is likely that bond owners are holding on to their bonds not because they still have an “appetite” for bonds issued by GOSL, but because they do not want to lose 39% prospective return (annualized). Investors’ behaviour patterns such as “escalation of commitment”, and “giving larger weight to the realized loss than to expected gain” may also be relevant here [Prospect Theory and related literature by Kahneman and Tversky (Nobel Prize winners in 2002].

Closing remarks

The economic downturn caused by COVID-19 is presenting unprecedented challenges to countries all over the world. Central banks in many countries have implemented different combinations of policy tools, including restructuring of external debts to face these challenges. Buying back their debt instruments is one of such tools. It is good to see that CBSL has explored the ways to reduce the external debt burden of GOSL. However, choosing IBS buy-backs to achieve this objective seems premature especially given the current financial situation of GOSL and the country.

The CBSL did not have funds to implement the intended buybacks. Even if it could raise funds for buy-backs, it was not a ‘prudent, priority use’ of such funds. As mentioned before, it is hard to see a profound ‘wealth enhancing’ rationale that underlies the CBSL’s policy decision to reduce ISBs to 10% of GDP in three years. However, if funds are available with lower opportunity costs, and if buying back stands at the top of the “opportunity set” available to GOSL, then buying back and redeeming outstanding bonds before they mature can be a wealth-enhancing proposition in the future.

The writer is not at all critical of CBSL for exploring the possibilities. Buying back bonds, when it is permitted by the bond deed like in the case of these bonds, can be used as a tool to enhance the wealth of the issuer. The author did not have an opportunity to study the bond deeds to identify the types and nature of restructuring permitted. According to the Advocata Institute, 36% of the GOSL’s outstanding bond issuances contain classic collective action clauses which make harder to restructure (reported in the Daily Mirror, 15 October). If the CBASL is going to retain its policy of buying-back bonds these legal aspects must be thoroughly studied by lawyers experienced in such matters.

(Professor Samson Ekanayake is a former Head of Finance and Financial Planning disciplines at Deakin University, Australia. He has held several senior management positions in academia and commerce during a career spanning over 40 years.)