Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Friday, 16 July 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The decision to ban agrochemicals has been taken on misinformation provided to the President – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

The ban on importation of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides was imposed on 6 May through the Extraordinary Gazette Notification No. 2226/48. This was one of the 20 activities approved by the Cabinet of Ministers under the theme ‘Creating a green socio-economy with sustainable solutions for climate change’.

The ban on importation of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides was imposed on 6 May through the Extraordinary Gazette Notification No. 2226/48. This was one of the 20 activities approved by the Cabinet of Ministers under the theme ‘Creating a green socio-economy with sustainable solutions for climate change’.

The theme carries a long-term noble objective. However, the approach suggested for achieving the objective in the agriculture sector is not practical at all, even to maintain the current levels of crop production and productivity in the country thus, threatening food security.

Use of organic matter as a soil conditioner, and a supplementary nutrient source to a certain extent, have always been encouraged by many and practiced by farmers at different levels with various objectives. Organic farming is a specialty practice with product and process certification. It has a good but niche export market and also a promising foreign exchange earner. It is heartening to see that organic fertiliser production and compost production are taking place at a mass scale in the country, in response to this policy decision.

However, even with novel technologies, organic fertiliser and/or compost alone would not suffice in providing the required nutrition to plants at the correct time and quantities. A high crop productivity could be achieved when appropriate strategies are used to match the patterns of supply of nutrients from fertiliser (organic or mineral) and absorption of nutrients by plants/crops. This aspect has been much deliberated and hence, I will not elaborate on the same further.

We have now learned that the decision to ban import of agrochemicals was made due to speculations that the farmers in many parts of the country suffer from many Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) including kidney disease and also that the serious damages done to the environment with the use of mineral fertilisers. Furthermore, we were also informed that the Government spends huge amounts of foreign exchange annually on mineral fertiliser imports, inferring that there is a foreign currency issue that has also set the base for this decision.

The author of this article strongly believes that the decision to ban agrochemicals has been taken on misinformation provided to the President. Hence, the correct facts regarding the mineral fertiliser and their utilisation in Sri Lanka are presented in this article to debunk the unscientific justifications made by some individuals and groups that would probably have led to the policy directive.

Fertiliser imports and use in Sri Lanka

The ‘Kethata Aruna’ fertiliser material subsidy program was introduced in 2005 and dismantled in 2016-2017 replaced by a cash subsidy. The fertiliser material subsidy was re-introduced thereafter since 2018 in different forms. The import of mineral fertilisers is governed by the Regulation of Fertiliser Act No. 68 of 1988. This is under the purview of the National Fertiliser Secretariat (NFS). It must be noted that all quantities of fertiliser imported are decided by the NFS based on the advice and recommendations of the respective state agencies, i.e. Department of Agriculture, research institutes responsible for tea, rubber, coconut, sugarcane, etc.

The quantities to be imported are decided annually considering the existing extent (for perennial crops) and anticipated extent (e.g. annual food crops) of cultivation, considering the fertiliser recommendations given by state agencies based on crop-nutrient requirements.

For example, according to the NFS, the anticipated paddy cultivation in Sri Lanka in 2021 (both Yala and Maha seasons together) is 1.3 million ha and the required quantity of fertiliser to be imported is 247,000 mt of Urea, 61,000 mt of Triple Super Phosphate (TSP) and 74,000 mt of Muriate of Potash (MOP).

As per Government regulations, all paddy fertiliser (subsidised fertiliser) can only be imported and distributed through the Government-controlled mechanism. Excluding paddy, the anticipated fertiliser imports in 2021 to provide required nutrients to other food crops and perennial/plantation crops for an estimated extent of 1.47 million ha amounts to 298,983 mt of Urea, 102,928 mt of TSP and 243,743 mt of MOP. There are other types of fertilisers also imported under the licenses issued by NFS. Further, excluding the subsidised fertiliser for paddy, the NFS issues permits to the private sector to import fertiliser for other crops on an agreed quota system.

It is important to note that no individual or agency in Sri Lanka (Government-owned or private sector) can import fertiliser without an import permit issued by the NFS. The import permits are issued based on the actual crop requirements and anticipated cultivated extents. Therefore, it is clear that the quantity of fertiliser imported to Sri Lanka is not done on an ad hoc basis, but on a clear scientific methodology. Farmers should receive fertiliser at quantities decided by the NFS as recommended by the state institutions, and up to what is required by the country – not in excess.

When this is done following an accepted procedure, there is no point in arguing that Sri Lanka is importing more ‘chemical’/synthetic fertilisers than what is required in a given year. However, many policymakers and professionals still blame farmers for overusing fertiliser, which theoretically cannot be true as the fertiliser quantities are imported based on the actual crop requirements as estimated by the state agencies.

If the correct quantities of fertiliser are imported and their distribution is regulated (assuming no illegal entry of fertiliser to the country), the claims for overuse of fertiliser should not have arisen. Further, there should be false alarms ringing to politicians and decision makers that undue quantities of fertiliser have been imported with a huge pressure on foreign exchange drain, and causing severe impacts on the environment. Such false alarms would also have provided a window of opportunity for some to create the ‘fertiliser demon’.

Once the fertiliser or any other agricultural input is heavily subsidised, their misuse is the most highly likely (mal)practice. In this context, if the state agencies and the NFS have done a fairly accurate estimate for the fertiliser requirement and imports, the best option available would be to remove the fertiliser subsidy (at once or in a phased-out manner) and make ‘chemical’ and organic fertilisers readily available in the market allowing the farmers to take a judicious decision on the fertiliser use on their own.

Farmers also need proper training on the judicious use of ‘chemical’ fertilisers with organic matter, i.e. integrated plant nutrient systems (IPNS), and obviously pesticides. Without such well-targeted capacity building, it is not wise to put the blame on the farming community for misusing or overusing agrochemicals and thereby polluting the environment.

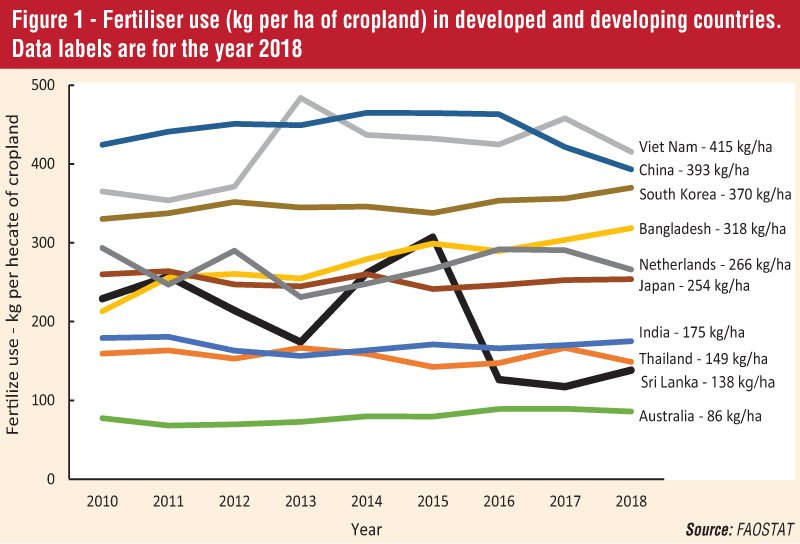

Furthermore, some scientists and professionals claim that Sri Lanka uses the highest quantity of fertiliser among those in Asia (or South Asia). The latest FAO statistics available for all countries clearly indicate the low rate of fertiliser use in Sri Lanka (Figure 1), except for few years. Regarding pesticide use, too, Sri Lanka stands at very low rates of application. Hence, the popular notion of heavy use of fertilisers leading to health hazards and environmental pollution is an erroneous conclusion drawn without considering the scientific facts.

Eco-friendly fertiliser use

Eco-friendly fertiliser use

Organic amendments in agriculture, is not an alien practice to our farmers. The IPNS in crop production; i.e. the use of organic matter with ‘chemical’ fertilisers, has been recommended since time immemorial to improve the fertiliser and nutrient use efficiency and to minimise environmental pollution caused by leaching. The Department of Agriculture (DOA) has formally promoted the adoption of Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) to minimise any misuse of agrochemicals, since 2015.The GAP program has started gaining momentum in 2020.

Prior to the current policy directive, the Ministry of Agriculture even had plans to distribute organic fertilisers produced by different private companies to selected paddy growers during 2021 Yala season, together with ‘chemical’ fertiliser. The proportionate allocation of fertiliser for this IPNS was 30% organic fertiliser, and 70% urea, 50% TSP and 70% MOP as per recommendation of the DOA. Similar proportions were also used in the case of bio-fertilisers. This was an excellent initiative. However, the current policy directive will derail this good practice and would create disastrous impacts on crop production.

Low quality fertiliser imports

The Sri Lanka Standards Institute (SLSI) has set up standards for the ‘chemical’ and organic fertilisers to be used in Sri Lanka. The NFS relies on such standards, which are adopted for any fertiliser used in Sri Lanka (imported or locally produced). The sparkling revelation made by the Minister of Agriculture, which also appeared in the Government Audit Report of 2020, says that 55 fertiliser analysis reports have been tampered to allow inferior quality fertilisers to be released in Sri Lanka.

Release of 12,000 mt of imported TSP in 2020 having heavy metals such as lead (Pb) contents higher than the limit set by SLSI (maximum Pb content allowed in TSP is 30 ppm) was reported in electronic and social media, and also raised at the Parliament causing serious concerns over the mishandling of state affairs by certain officials. Hats off to the Minister of Agriculture who took stern punitive action against some officials for tampering the analytical reports of the fertiliser samples.

Recently, we also heard that organic fertiliser has been imported without proper approvals. Any plant-based organic fertiliser requires the approval and a permit of the DG of the DOA under the Plant Protection Act No. 35 of 1999. We also heard that such imports have been done in the past, which should not have been allowed due to multi-folded negative impacts than what is even speculated against agrochemicals. The efforts made by officers of the DOA and the Sri Lanka Customs, and no signs of political interference in releasing the imported consignment is noteworthy and require special commendations.

All such incidents indicate that the well-articulated fertiliser regulatory process has been breached by some people with vested interests. These are daylight robberies of government (people’s) money and efforts to rape the environment (similar to misuse of any other agricultural inputs). The penalties have been imposed in some cases but it is high time that openings for malpractices be sealed-off so that even in the future, import of any type of fertilisers is stringently governed.

The case of non-communicable diseases

Agrochemicals are generally considered as the causal factors for many of the non-communicable diseases (NCDs), especially the chronic kidney disease of uncertain etiology (CKDu). Such unproven ideology has been forced into minds of people who are suffering from the disease. Some even dubbed CKDu as ‘Agricultural kidney disease’. This propaganda campaign has brainwashed not only the unfortunate patients, but also the general public and policymakers and thus, creating fear against an important agricultural input.

In those claims, nutrients are probably not targeted as the causal factor for NCDs. For example, both mineral and organic fertilisers provide the essential plant nutrient ‘Nitrogen’ in the form Nitrate (NO3-) or Ammonium (NH4+) ions to be taken up by plants. Further, amino acid supplements providing 13-19% nitrogen can also be taken up by plants directly. The loss of Nitrates in the ecosystems, especially polluting ground water, can be minimised by split application of fertiliser (which is the recommended practice) and with the application of organic matter (manure, fertiliser or composts) as soil amendments.

The organic amendments have limited plant nutrient supply (e.g. 1-3.5% N, or rarely up to 6% depending on the source). Lack of soil organic matter (e.g. sandy soils) will create a negative scenario as observed in isolated incidents such as Kalpitiya area. Hence, the popular argument on the impact of fertiliser on human health and environment issues could mainly be focused on the potential contaminants in fertilisers, such as heavy

metals.

Nitrogen being the most difficult element to tackle in nature, let me take an example for urea. The maximum limits allowed by the SLS standards for Arsenic (As), Cadmium (Cd) and Lead (Pb) for urea fertiliser used in Sri Lanka is 0.1, 0.1 and 0.1 ppm, respectively. As for solid organic fertilisers the corresponding values are 3, 1.5 and 30 ppm, respectively (SLS 1704:2021). This indicates the danger that could arise from application of solid organic fertiliser with the objective of providing nitrogen to the crops.

Extremely low and stringent heavy metal limits have been adopted for urea as there is hardly any chance for such contamination, but the maximum allowable limits for such elements in solid organic fertilisers are higher owing to higher potential for contamination. If the municipal solid waste is used as the source to produce composts for agricultural land, then the maximum allowable limits for As, Cd and Pb are 5, 3 and 150 ppm (SLS 1634:2019), respectively. This needs no further explanation to prove the fact that organic fertiliser targeting Nitrogen could pollute the environment at a higher level

than urea.

The popular talk on ‘Agrochemicals as a causal factor for rising incidence of cancer in Sri Lanka’ has surfaced again. I am not a medical professional to provide details on such. However, as per Figure 1, the amount of fertiliser added per ha of cropland in 2018 in Australia was 86 kg, Bangladesh 318 kg and Sri Lanka 138 kg. But the statistics presented by GLOBOCAN 2020 revealed that five-year prevalence in cancer as a proportion for 100,000 population in Australia is 3,172, Bangladesh 164, and Sri Lanka 354. I will leave it with the learned readers to draw conclusions.

The ‘demon’ created in people’s minds with respect to use of fertiliser and its impact on NCDs such as CKDu was comprehensively refuted recently by the Chairman of the National Research Council (NRC) of Sri Lanka, appearing in a popular TV discussion. The Chairman/NRC clearly stated that the most recent research completed under the funding from NRC has concluded that not drinking adequate volumes of water and the high fluoride content in ground water as the two major causal factors for the CKDu in Anuradhapura area. He further stated that the disease is not due to heavy metals and that this information has been provided to the Ministry of Health.

Need for evidence-based policy making

National policies need to be set based on evidence. Policies driven by advice from those who want their whims and fancies to be realised at the expense of national budget will result in detrimental and irreversible impact on the national economy. Further, the spread of unproven and non-scientific ideologies across the society have already made complete change in focus of the efforts made to find solutions to major issues in the Sri Lankan society, including finding causal factors for human health related problems such as CKDu.

Many intellectuals have alarmed that the import ban on ‘chemical’ fertilisers would lead to food shortages and high food prices. In this context, Sri Lanka is likely to import a major portion of basic food needs such as rice, as experienced by Bhutan in their failed attempt to become the first organic country by 2020, adding a huge burden to the government treasury.

The fear generated on agrochemicals thus, seems to be due to ‘chemophobia’ (irrational fear of chemicals) of some people, who have unduly fed the same into the authorities. The President and the Cabinet of Ministers should not fall prey to ideologies spread by some people that could have unprecedented negative effects, in making decisions in relation to the country’s economy. It is still not late to revisit the decision to ban the import of agrochemicals. Being misinformed is more dangerous than being not informed.

(The writer is attached to the Faculty of Agriculture, University of Peradeniya.)