Monday Jan 05, 2026

Monday Jan 05, 2026

Monday, 25 June 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Bank of Ceylon and People’s Bank are the bankers to the GOSL, whose current accounts with the two State banks faithfully keep the country’s administration ticking and as a result of which there is no fear that the wheels of the economy will grind to a halt like it often threatens to happen in the largest economy in the world in the US, where the government’s budget is subject to the whims of Congress

In the name of financial stability, can we please get off the Basel III Bandwagon?

Time and again over the last year, and more recently in fact, the sceptre of Basel III has raised its head in the print and electronic media. What is of immediate concern is the attempt by the rating agencies to dare to question the stability of the banking giants of our financial system – the two State banks – and with the swathe of the capital sword of Basel III, attempt to shake public confidence in the country’s banking icons.

This obsession with an international capital standard which has little or no relevance to financial stability in general, or banking stability in particular, in the Asian context, by the so-called gatekeepers of the economy of this country, is, to say the least, damaging to banking stability and highly irresponsible, for the undue publicity given in the print media and even on the TV channels, which has caused uneasiness in the minds of the common masses who are the predominant constituents of the banks in focus.

The State banks have often been easy prey for the slightest hint of perceived financial unsoundness by financial analysts, auditors, rating agencies et al, and their dominance in our financial system is often perceived as a distortion to the functioning of the “market” by the International Financial Institutions (IFIs). This was until the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) exploded the myth of the market manthram, when the champions of the free market themselves were forced to recapitalise the failed private sector banks en masse, even those residing right next to the “old lady of thread needle street” and with the Government of Her Majesty (spearheaded by Prime Minister Gordon Brown) being represented on their boards. I am not sure that these holdings have still been divested.

This was the situation in the US too, where the TARP was created by the US Fed, hot on the heels of the UK initiative, to recapitalise the many US banks that failed. Even though these measures were hitherto rejected as socialist policies, they had to be resorted to as a result of the abject failure of the market to find a solution and which mechanism permitted the unbridled expansion of mega financial institutions with assets far in excess of the GDP of these countries.

The State banks in Sri Lanka and in most of S.E. Asia, however, have always been and will always be, an integral part of our financial landscape in view of the key developmental role they play in the economies of these countries and through which government economic policy is largely disseminated for the benefit of the common masses.

Therefore this persistent focus on Basel III by the rating agencies in particular, to the exclusion of all else in the banking sphere, is entirely uncalled for, for the following reasons:

What is worthy of consideration from the above and which should therefore receive the attention of the regulators and the analysts are:

However, as with anything that is developed or formulated and foisted on us by the West – these dictums are looked on as the gospel truth, as trendy, regardless of their antecedents, their track record or their propriety in our financial system. This can be directly attributed to our colonial mindset, the vestiges of which are hard to erase in most Sri Lankans.

Surrendering the stability and regulation of our financial system to the Basel Committee

They have been subject to highly damaging publicity in the media about their perceived shortfall in meeting the Basel III capital standards by 2019. It behoves one to ask “have the stability of the country’s financial system and its regulation been surrendered to the Basel Committee?

The State banks’ indomitable position in our financial system as financial intermediaries

As bankers to the GOSL

More profoundly, they are the bankers to the GOSL, whose current accounts with the two State banks faithfully keep the country’s administration ticking and as a result of which there is no fear that the wheels of the economy will grind to a halt like it often threatens to happen in the largest economy in the world in the US, where the government’s budget is subject to the whims of Congress.

Therefore to cast aspersions, or even the slightest doubt, on the ability of the two state banks to continue in business, and to questions their stability, based on a single regulatory standard imposed by an international standard-setter with no relevance to this country and, more importantly, whose credibility is seriously at stake, based on its track record, is illogical and ludicrous and reflects a basic lack of common sense. It is highly obnoxious to say the least and is a result of the level of ignorance in those who have the impudence to throw caution to the winds and to make pronouncements that can prove to be reckless and unfounded in ignoring all other financial soundness indicators that reflect the sound operational performance of these banks right up to the last financial year 2017.

Why has the significant development role played by the two State banks in this country and which, through their high level of financial intermediation of as much as 75% of credit to deposits, disbursed across the economy, not been recognised – the recent, highly commendable initiative of the People’s Bank in a one page press release in Daily FT of 11 June, for micro and SMEs across the country entitled ‘Enterprise Sri Lanka’ in response to the President’s call from the State banks to support these sectors, not received any acclaim at all from the many financial analysts, for the immense contributions these initiatives could make to economic growth in Sri Lanka.?

Operational performance

It is imperative that the rating agencies shift their emphasis to the operational performance of the state banks that reflect their capacity to generate the surplus necessary to augment capital and, more importantly, to be liquidity solvent to meet their liabilities as they fall due and to service their constituents, without the slightest doubt of their going concern ability.

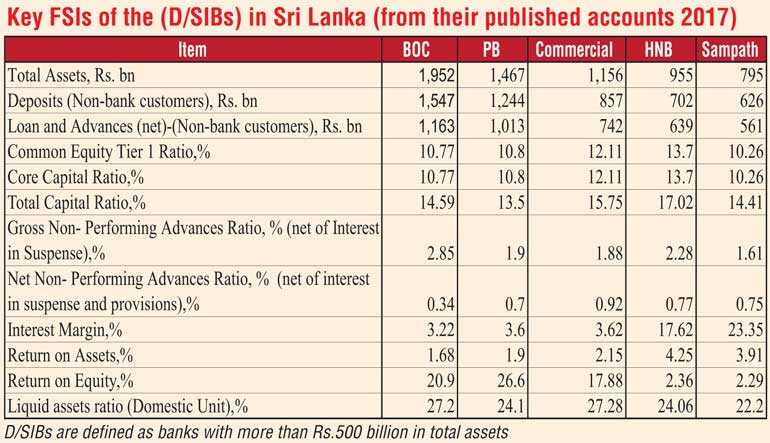

The stellar performance of the two State banks which have performed remarkably well operationally, in the last financial year (2017), on par with their private sector competitors and their dominance in our financial system has to be acknowledged despite the inherent challenges they face as state banks and despite pressure on their interest margins due to high intermediation costs associated with their structure, unlike their private sector peers.

Given the importance of the two State banks in the country’s financial system, it is strange that the Sri Lankan regulators have not thought it fit to give due publicity to the status quo of Sri Lanka’s banking system vis-à-vis Basel III.

In my mind the relevance of Basel III, in the context of Sri Lanka’s existing strong regulatory system, is not a sine qua non for a stronger banking system by any measure. The rating agencies in particular need to do a more in-depth analysis of the directive in the perspective of the existing regulatory framework and its antecedents. More profoundly, on the implementation aspects on economic growth. This is what most countries are doing and due to serious concerns are in no hurry to meet the timelines.

The uncanny faith in the attitude of the rating agencies to make Basel III the panacea for all ills relating to financial soundness in banks is thus highly illogical with no regard at all for the track record of the BC in this regard and puts into question the credibility of the rating agency.

The importance of the current status quo

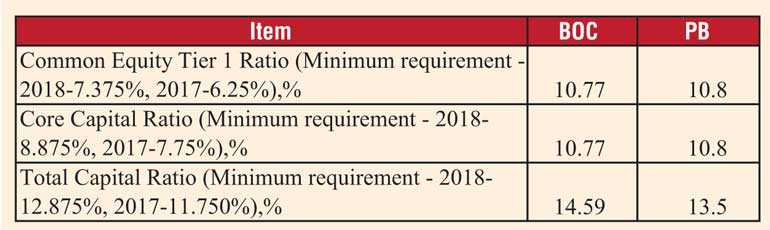

All our banks in Sri Lanka are Basel III compliant on the capital formulas – both on the Common Equity Tier I (CET1) and on the Capital Conservation Buffer (CCB), well before the specified timelines – primarily by default – if one looks at the published accounts of the banks for the financial year 2017 where Tier I capital which was mandated to be 6.25% is invariably at 10% or over for the two State banks as well as all the D-SIBs!

The industry ratio for total Tier I capital as at end 2016 was at 11.4% which is higher than the prescribed 8.5% in 2019! What is important is that the Domestic Systematically Important Banks (D-SIBs) which represent over 70% of the banking industry, are all well within the required norms, much before 2019. The comfortable and compliant position of the State banks which is a moot point, is seen in the table and is completely tenable by any yardstick.

They are therefore fully compliant and even exceed the specifics for 2017 and 2018 and are not far short of the target for 2019 which they are quite capable of achieving through efficient capital and RWA management.

By the same token, one may ask – why has the Sri Lankan banking industry not been applauded for having met the Basel III timelines well in advance of their Western counterparts, thanks to the superior regulatory and supervisory regime and wisdom of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka which has prevailed over the years?

When the first of the Basel III dictums was announced that (CE) or paid up capital, was to be increased to 7%, almost all Sri Lankan banks had almost all their Tier I capital in CE at 10% or even more because in our superior wisdom we recognised only common equity as paid up capital. All these exotic capital instruments or capital hybrids which are commonplace in the Western financial system and which were admitted and recognised by the BC, had no place in our financial system.

Neither did the Basel Committee have the mandate to dilute the pristine definition of capital with a predominance of hybrid capital instruments, primarily to accommodate the strong lobby of the Wall Street banks whose interests are well represented on the BC and which caused the GFC!

It is indeed sad that the Sri Lankan banking industry and indeed Sri Lanka, did not receive any kudos for this achievement. Instead the Rating Agency looked at their crystal ball and saw only the negative picture of these ratios coming under pressure, if the growth of risk weighted assets (loan growth) and capital do not move in sync.

We don’t need Fitch to point this out – this is common sense and can apply to any of the D-SIBs purely because banks are dynamic institutions where their balance sheets evolve on a daily basis every minute 24/7!

However, what is important to note is that they are quite capable of managing it through the ICAAP which is the most important capital management tool in the hands of the regulators to enforce and which is being closely monitored by the regulators who will not hesitate to use their national discretion to move the timelines if necessary for compliance, like most other countries are doing viz. Singapore, Hong Kong and Australia to name a few (Reuters).

Is Basel III the holy grail of bank stability?

Of all the financial soundness indicators in a bank, capital is the last resort in the event of a bank failure. To take the example of the oldest UK bank, the 100-year-old Barings Bank failure, no amount of capital could save it when the losses made were well in excess of its capital. And so it is with the Basel Capital standards which are the absolute floor – ranging from 8 to 14.5% of risk assets, of which pure capital or unadulterated capital of a permanent nature, will be only 4.5%. and which previously under Basel II was, thanks to the wisdom (sic!) of the Basel Committee, only a mere 2%! How much common sense does it take to make this capital standard the holy grail of bank stability?

So what is the fall-back if the State banks are not Basel III compliant as perceived? Their healthy and sound operational performance undoubtedly.

Consequently, it follows that the bank has to be operationally strong on all other FSIs to be able to generate an operational surplus which can be used to augment its minimum capital continuously and to serve as a capital cushion for unforeseen losses that may arise in the future. This then is where the analytical focus should be – on the operational performance of the banks which requires more in-depth scrutiny of the results of the productive use of assets and the prudent management of their risk exposures. Are the rating agencies not capable of undertaking this analysis and to put Basel III in its proper perspective?

Capital reserves

I wish to strongly reiterate my comments previously on the subject that these capital reserves were mandated from the inception of bank regulation in this country and, as a result, the banks all have built up adequate reserves, much before the Basel Committee even thought about this most fundamental prudential measure which they now call the capital conservation buffer CCB – in their characteristic, grandiose jargon!!

The importance of liquidity over capital

Liquidity management is much more important than capital in the short term, and here too our banks have a mandatory stock of liquid assets as well as a flow analysis through liquidity gap management, to ensure adequate liquidity to meet their day to day liabilities and to avoid systemic panic which can crash the whole banking system. These regulations have existed from the inception of bank regulation in this country and is precisely the reason the Asian banking industry proudly stood tall over their fallen peers in the West in the GFC, solely because of their strong and far superior, prudent management and regulatory regimes, the prudent components of which are only now being introduced by the BC.

More profoundly, and by the same token, one can very well ask:

More productive use of scarce supervisory resources

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka would do well to use its bank and non-bank supervisory resources to better use than to devote so much time and attention to the complex formulas of Basel III and to analyse in depth, like almost all countries in S. East Asia and even in Europe are doing, the economic impact of its implementation on the key economic sectors of our country. Has the Monetary Board been presented with such an analysis?

With all due respect I would earnestly request the Governor and the Monetary Board to take the cue from the Reserve Bank in neighbouring India, and direct its scarce supervisory resources to the risks that may be lurking in our financial system – The RBI has caused a thorough overhaul of the non-performing portfolios of the Indian banking sector as a result of which banks are being forced to sell assets in a fire sale and recover their NPA. This applies across the board to the mega corporates that abound in the Indian financial system.

The Department of Bank Supervision would do well to get off the Basel III bandwagon and concentrate on banking stability in the context of Sri Lanka’s financial system and not in the context of an international financial system with all its hybrid capital instruments and derivative products which bear absolutely no semblance at all to our traditional banking system. Have they ever paused to consider what all these requirements mean in our context and whether they are relevant?

I wish to strongly recommend that our scarce supervisory resources should be used more appropriately for domestic development and in the best interests of economic growth.

More profoundly, it has to be recognised that Basel III reflects the existing regulatory standards applicable to the industry and which have been in force for well over half a century!!! The banks just need to inculcate a capital planning mindset to ensure that capital and asset expansion move in sync and that they are not overleveraged.

It is indeed convenient and fashionable to talk of adherence to international benchmarks which may mislead the public into believing that everything is hunky dory in our banking system. This is the convenient way out of looking more deeply into risk exposures that are lurking in the banking and non-bank system and which are not receiving the attention they deserve because of the preoccupation with Basel III.

I wish to strongly reiterate that the Central Bank of Sri Lanka and the rating agencies can learn from the wisdom of Ravi Menon, the Managing Director of MAS, who summed up the concerns on Basel III very aptly and so eloquently when he stressed the importance of taking a holistic perspective in this final stage of the Basel III capital reforms and cautioned that:

I for one would be happy to attend a session presented by the Director of Bank Supervision on the 600-page Basel III directive, just to be able to understand its impact and relevance on our financial system.

To quote from Andrew Haldane, Bank of England Executive Director, who described the intricate structure of Basel III that the new prudential provisions resulted in: “a ballooning in the number of estimated risk weights. For a large, complex bank, this has meant a rise in the number of calculations required from single figures a generation ago, to several million today.” [Haldane (2011)]

That increases opacity. It also raises questions about regulatory robustness, since it places reliance on a large number of estimated parameters. Across the banking book, a large bank might need to estimate several thousand default probability and loss-given-default parameters. To turn these into regulatory capital requirements, the number of parameters increases by another order of magnitude.

Besides, was the phenomenal failure of Basel II ever brought into question in the aftermath of the GFC, and was the BC held to account considering the fanfare with which it was first launched to replace Basel I, almost a decade ago, as the magic wand over banking soundness; where no estimate has been made of the tremendous cost of the many BC meetings that took place across the globe over almost a decade? To date they have not been, by any international financial institution, except for a few courageous men like the eminent Andrew Sheng and a few other US financial experts who dared to question the credibility of Basel II.

It is not difficult to understand the thundering silence of the rating agencies when they themselves had contributed in no small measure to the crisis and have also not been held accountable to date.

Analytical considerations for rating agencies

Regulatory Capital Arbitrage under Basel II and III

Models risk: These internal models, in fact, do not always reflect the underlying credit risks of different exposures and may foster regulatory capital arbitrage on a massive scale.

In view of the cost of implementation of Basel II which far outweighed the advantages, if any, of risk differentiation through the use of internal risk models – particularly where banks were unable to influence the pricing of credit as a result of lower capital charges to low risk borrowers, most banks in the industry opted to stay with Basel I at 100% risk weights and a higher capital charge. Particularly with the indigenous banks, this was in our favour as they had more capital than if they had used their own internal models which would have invariably been tailored to induce less capital. Our regulatory staff too were not equipped to validate these models. This was the time the Basel II software vendors had a field day, thanks to the Basel Committee, hawking their expensive internal ratings models. (Parliamentary Commission on banking standards – An accident waiting to happen – the failure of HBOS.)

The requirements of the Basel II framework not only weakened controls on capital adequacy by allowing banks to calculate their own risk-weightings, but they also distracted supervisors from concerns about liquidity and credit and the supervisory neglect of asset quality exemplified in the failure of the banks in the UK –

Regulatory discretion

Some of the very pertinent issues raised by Andrew Sheng, the eminent former central banker and financial regulator, in a study carried out by him on the impact of Basel III on Asian economies, are worthy of consideration:

The experience of the FSA (Report of the Banking Commission)

Basel II took much longer to implement than expected. It was a complex and resource- intensive process, both for the FSA and the firm, and the risks crystallised before that regime had time to bed down properly. No action had been taken in the interim to deal with HBOS’s increasing risk profile.

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka would do well to look at the experience of the UK and ensure that our own Bank Supervision staff are not engrossed in the complexities of Basel III to the exclusion of all other soundness indicators that may be evident in the banking system.

Considerations for the rating agencies and for the Central Bank of Sri Lanka – Fit for Purpose

The complexity of the Basel III framework

This is the type of analysis that the rating agencies and the regulators should be undertaking on the impact of implementation on economic growth in the context of Sri Lanka’s economic sectors. Several countries are doing so – A Reuters report by Michelle Price from Hong Kong reports: “Singapore to postpone bank capital rules: follows Hong Kong, Australia delays”.

It also states that policymakers are, after a decade of rule-making under Basel III, more concerned about prioritising growth over yet more complex banking regulation. I believe the Central Bank of Sri Lanka too should follow suit and take the cue from our neighbouring countries in this regard.

Conclusion

The former senior Deputy Governor of the Central Bank too has been quoted by Fitch to support their conclusions on the two state banks, but the negative implications referred to in his comments have not been elaborated which makes the comment very general without any definite identification of what can happen if the implementation timelines are not met – leaving the public wondering if their stability is at stake.

These negative implications, albeit marginal, would be only if they were internationally active banks, and needed to have recourse to the international market for their sustenance. This is definitely not the case for the two state banks and it is their national importance as bankers to the people of Sri Lanka and to the GOSL, and their contribution primarily to the country’s economic growth and not to the bottom line – a position unparalleled by any other banks in this country, that Is so profound in this whole sorry saga that they have been subjected to.

(The writer is ex-Director of Bank Supervision and Advisor to the Governor of the CBSL, a freelance writer and independent consultant on financial regulation.)