Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 4 October 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The recent violent attacks led by some Buddhist monks against a small group of asylum seeking Rohingyas have brought the Burmese reality into Sri Lanka. The Mahanayakas have not condemned the extremist incidents, although the incidents constitute the polar opposite of the basic tenants of Buddhism and Ahimsa (non-violence), not to speak of Metta (compassion). It is quite unlikely that they would condemn, or criticise, other than condoning directly or indirectly because of the reasons that this article is going to discuss.

The recent violent attacks led by some Buddhist monks against a small group of asylum seeking Rohingyas have brought the Burmese reality into Sri Lanka. The Mahanayakas have not condemned the extremist incidents, although the incidents constitute the polar opposite of the basic tenants of Buddhism and Ahimsa (non-violence), not to speak of Metta (compassion). It is quite unlikely that they would condemn, or criticise, other than condoning directly or indirectly because of the reasons that this article is going to discuss.

This is not the first time that Rohingya Muslims have appeared in Sri Lankan shores as asylum seekers, although compared to the numbers who have reached India or Malaysia by boats, these are quite insignificant. Minister Mangala Samaraweera has given the details in a statement condemning the attacks. Like in all the previous instances, they are under the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) care, and would be repatriated to a third country because Sri Lanka is unfortunately not in a position to take them as refugees.

That can be considered understandable, given Sri Lanka is a poor country with its own internal problems. However, that is not a reason to be inhuman when they reach here or when they are processed by the UNHCR to be sent to a third country. In recent times, we have seen pictures and videos of thousands and thousands of Rohingyas fleeing Myanmar (Burma) to Bangladesh including children, women, sick and old. They are not coming here, to be too alarmed. They are also now facing resistance in Bangladesh showing that these problems are intertwined with poverty, insecurity and political conflicts.

Whatever the reasons triggered the recent events, as a person who have visited some of these areas for work and research purposes, and who has written on them, the conditions of these ethnic minorities are quite appalling both politically and socio-economically in Myanmar. This is particularly the case of Rohingyas. Of course the conditions are no better of the majority Buddhist Burmans particularly as a legacy of the army rule and Myanmar being a poor country. That is one reason why they should unite, and not fight each other. The army officers function in that country as feudal lords and the Buddhist hierarchy as their close associates.

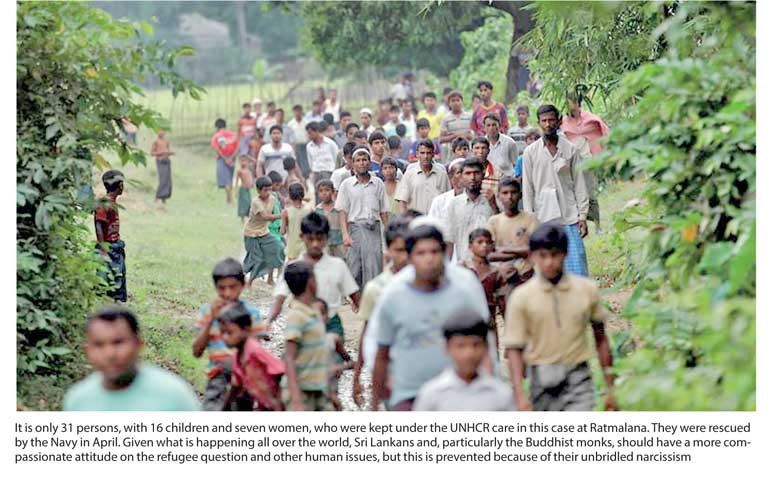

It is only 31 persons, with 16 children and seven women, who were kept under the UNHCR care in this case at Ratmalana. They were rescued by the Navy in April. Given what is happening all over the world, Sri Lankans and, particularly the Buddhist monks, should have a more compassionate attitude on the refugee question and other human issues, but this is prevented because of their unbridled narcissism. How come they are so backward, narrow minded and selfish? These are the broader issues that I am raising in this article. Is it lack of education, awareness, knowledge about the international affairs or Metta?

As reliably reported, Sinhala Ravaya was the main organisation behind the violent protests on 26 September against Rohingya asylum seekers. Sinhala Ravaya is one of the brotherhood organisations of the Buddhist extremist ‘969 Movement’ led by Ashin Wirathu in Myanmar. They were behind many provocations and violent atrocities against Rohingyas. Wirathu was even sentenced to 25 years imprisonment in 2003, but released in 2011.

It is quite inhuman that one organisation chase a particular group of people from one country, and when they come to the other country, the other organisation protest against them violently. As both organisations are led by some Buddhist monks, serious questions arise about the Buddhist Sangha, no social analyst could easily ignore.

Why Buddhist Sangha are so extremist on religious, ethnic, political and social issues? Is it possible to ignore the tendency as limited to some Sangha? Then why many others and particularly Mahanayakas are silent? Or have they ever stood for any democratic or progressive cause?

tendency as limited to some Sangha? Then why many others and particularly Mahanayakas are silent? Or have they ever stood for any democratic or progressive cause?

There is no question that almost all religions have extremist and violent tendencies. This is why some philosophers (i.e. Karl Marx) have criticised religion in general, and people in many democratic countries have become non-believers or secular. It has been a common phenomenon in pre-modern societies of all countries, that religion was used by authoritarian rulers as an instrument of ideological control. That is how religion and State became closely linked to each other in addition to feudal links. Therefore, the separation between the State and religion was considered a necessary task in democratic transformation.

If religion can serve a purpose in spiritual harmony, then it can also serve a purpose in social and political harmony as well. That is what Dharmasoka intended in promoting Buddhism and introducing Buddhism to Sri Lanka. His edicts are very clear on this subject. However, for various historical reasons the purpose has become almost upside down or Sangha have placed Buddhism on its head. It is extremely doubtful whether these protesting monks have any harmony!

In observing extremist tendencies and violence in Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Cambodia, the present author previously raised the question whether Theravada Buddhism has a tendency towards extremism and violence, associated with ideological sectarianism? The article was titled ‘Some Questions About Violence and Theravada in Buddhism.’ In that article what was not discussed were the social bases of Sangha’s conservatism and, one may say, reactionary tendencies. These social bases are primarily feudal and those are the profound reasons why these Sangha and most of the Mahanayakas are resisting necessary social and political change in the country today.

One may ask the question, what is the connection between the recent Sinhala Ravaya protest and feudalism? The connection is via the type of ‘nationalism’ that Sinhala Ravaya, Ravana Balaya, the BBS and many others are advocating. It is not the type of ‘nationalism’ that the modern era witnessed (modern nationalism), or scholars like Earnest Gellner (‘Nations and Nationalism,’ 1983) or Eric Hobsbawm (‘Nations and Nationalism since 1780’) identified; uniting economies, different communities, liquidating feudal order and giving priority to the citizens. It may be ‘imagined communities’ to a large context, given the fact that most of the other feudal elements are now liquidated. However, it is out and out feudal and archaic in ideological terms.

Can there be any doubt that Thri-Nikayas are the continuously remaining feudal institutions in Sri Lanka? Some of the other Maha Viharas (big temples) must have changed; some continuing from the landed feudal roots, and others thriving through donations and commercial ventures, but mentality and practices primarily being feudal.

This is not to underestimate the progressive and enlightened role that some of the modern educated Sangha have played and still playing in the socio-political sphere. A particular mention should be mentioned about the Vidyalankara group in the Left movement in the 1930s and Ven. Udakandawela Siri Saranankara. Ven. Walpola Rahula Thero also played a major role in emphasising the philosophical side of Buddhism against ritualistic orientation. ‘What Buddha Taught’ written by him is one example. I was privileged to be recruited to the Vidyodaya University in early 1969, as a lecturer, under his Vice Chancellorship, and interviewed by him.

There was no question that under colonialism, the Buddhist Sangha had to undergo enormous difficulties and even humiliation. However, that is not a reason to go back to the feudal age or feudal nationalism after independence. When SWRD Bandaranaike stepped into nationalism in 1930s, although he thought it would be ‘modern,’ he himself invoked the ‘Genie.’ Although he wanted to rally the poor and disadvantaged Sangha, under his five constituency movement (Sanga, Veda, Guru, Govi, Kamkaru), those who took over the control were the feudal hierarchy, and they still try to control the State and politics.

When Bandaranaike wanted to give reasonable use for Tamil language (it was too late of course), who opposed? Who forced him to tear off the BC Pact? Who conspired and assassinated Bandaranaike? What is not so known is the Sangha opposition to the land reforms that Philipp Gunawardena spearheaded. Finally they were spared from the land reforms then, and thereafter under Mrs. Bandaranaike under pressure. This is how the feudal power of Maha Sangha kept intact. Therefore, there is no doubt why they are so conservative and resistant to change and wanted to control the State and politics. This is nothing personal, but institutional and structural, however they are responsible for their conservative and parochial ideas.

This is not peculiar to Buddhism or Buddhist organisation/s in Sri Lanka. This was the same in feudal Europe, Christian monasteries and abbeys possessing land and controlling the State and politics. However, this became largely changed through reformation and also democratic and parliamentary reforms. However, this remains still the case in some Buddhist countries. Sri Lanka is one and Myanmar is another. In the case of Thailand, the Buddhist Sangha also constitute a feudal remnant or force other than the Throne. Klumsuksa Itsara and Sulak Siwarak have revealed these feudal forces in their works, ‘Tearing Off the Mask of Thai Society’ (1981) and ‘The Unmasking of Thai Society’ (1984), respectively. They are Thai writers and not Westerners!

Even in China before the revolution, the Buddhist and Daoist monks were linked to feudalism, particularly through landlordism. Instead of reform, they were unfortunately controlled or suppressed. Dalai Lama became escaped and he himself has become reformed fortunately. He was one of the first to condemned or disapprove the treatment of Rohingyas in Myanmar. A similar suppression to China happened in Cambodia under Pol Pot, quite distortedly. While Buddhism is now resurrected, the monks are not allowed to enter into politics and even debarred from voting. Sri Lanka or even Myanmar should not go to that extreme, but refraining them from politics might be useful.

It should be admitted that the prominent Sangha influence in politics at present is detrimental to the democratic process and progress. Not all, but some are playing a dubious role quite harmful to peace and harmony in the country. There are others who are ‘taking fire under water.’ I am using a Sinhala idiom.

Take for example what particularly Asgiriya Nikaya is saying about a new constitution. It is not only about preserving the foremost place for Buddhism in the constitution. They are trying to dictate terms on all other matters and on devolution. My previous article on the subject was ‘Is There a Sangha State Behind the State?’ Is it acceptable in a democratic country, in the 21st century, to keep the minorities under the yoke of the majority rule and/or religion like in Myanmar? The Sinhala Ravaya attacks on Rohingya refugees are only another tip of the ice burg. The other issues underneath are more profound.

In symbolic terms, if the foremost place is preserved for Buddhism as a historical recognition, that can be acceptable. However, the present attempt is to link the State more closely to the Sangha. A link is already there through the Ministry of Buddha Sasana and the Vihara Devalagam Ordinance which is the feudal link. Even this can be acceptable, if the Sangha refrain from hegemonic dominance in politics.

One advantage in possible deconstruction of the situation is the most sophisticated philosophy in Buddhism. It is not only about Metta (compassion) or Karuna (kindness), but also about critical questioning of all what the controversial Sangha says and the feudal privileges that they unjustly entertain. This is about the application of Kalama Sutta. What I have not discussed here is the apparent unbridled narcissism that marks the ideology and behaviour of Sinhala Ravaya, Ravana Balaya and Bodu Bala Sena, leaving it for another day.