Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Wednesday, 27 May 2020 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

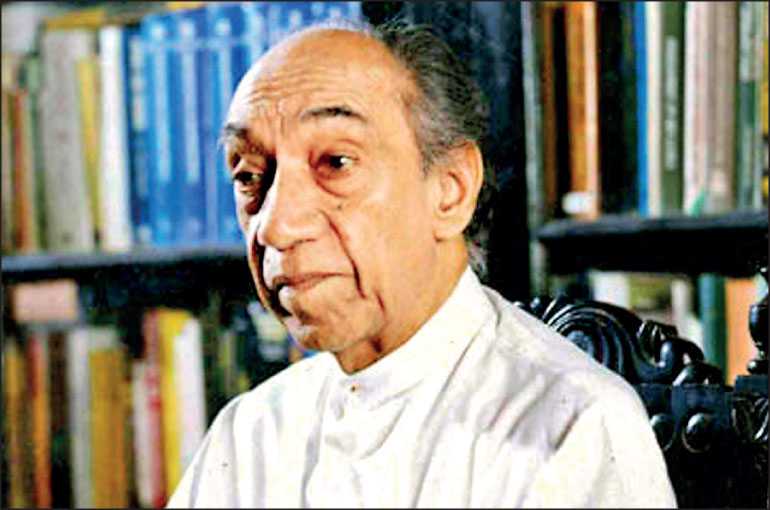

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa

President J.R. Jayewardene

Nandasena Gotabaya Rajapaksa who was sworn in as Executive President on 18 November 2019 has been in office for six months now. He has been compelled to cope – and continues to cope – with several challenges during his brief but eventful tenure.

However, it is not my intention to evaluate Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s presidential performance in this article. Instead I would like to focus on how the nature of the executive presidency has undergone transformation in a very unique mode in the past few months that he has been in office.

Due to exceptional circumstances, Gotabaya Rajapaksa is arguably Sri Lanka’s first “standalone Executive President not dependent on the Legislature” today. In this he may have surpassed even the presidential vision of Junius Richard Jayewardene who introduced the presidential system of government in 1978. Jayewardene, known popularly as “JR,” envisaged the powerful presidency functioning in tandem with Parliament. Even though JR wanted a president not dependent on Parliament, he always acted through Cabinet and Parliament and preserved the parliamentary system without trying to operate outside it.

Powerful President, no functioning Parliament

What we have today is a powerful president with a dissolved Parliament who steers the ship of state with the aid of a “caretaker” Cabinet and a Prime Minister who did not command a majority in the last Parliament. Although the country faces a health emergency in the form of the COVID-19 pandemic it has no functioning Parliament.

The “old” Parliament that was in existence at the time of the Presidential Election on 16 November last year was dissolved on 2 March this year by the President. Fresh elections scheduled for 25 April have been postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic spread. A fresh election being held on the newly fixed date of 20 June is virtually impossible. It is clear that the three-month deadline for a new Parliament to convene would not be met on or before 2 June.

The President is adamant in not wanting to rescind the 2 March gazette proclamation and bring the dissolved Parliament back to life. He is also reluctant to convene Parliament for a special purpose under Article 70(6) in response to an emergency. This may result in a Constitutional crisis after 2 June. Only the President elected with a 52% mandate last year will remain as a “legitimate” authority in a legislative vacuum after 2 June. The matter is now before the Supreme Courts and hopefully the Judiciary would soon restore clarity in a confusing situation.

Centralisation of power under Presidential authority

Furthermore President Rajapaksa’s style of governance under the prevailing circumstances has led to a centralisation of power under Presidential authority. Executive power is concentrated in the Presidential Secretariat and Presidential Task Forces set up by the President. The press releases issued by the President’s Media Division have acquired great importance and value. Key posts are held by a team of “all the President’s men” comprising an unusually large number of former defence services personnel regarded as Gota loyalists.

|

|

|

What seems paradoxical in the current situation is the fact that the 19th Constitutional Amendment had decreased the powers of the president and increased those of the prime minister and Parliament. There were many constitutional pundits who referred to a relatively powerful premier and comparatively powerless president in a post-19th Amendment scenario.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa is the first president to be elected in a situation where some powers afforded to President Maithripala Sirisena via transitional provisions have been rendered null and void. Yet the allegedly-disempowered executive presidency under Gotabaya appears to be vibrantly hyperactive while the supposedly-empowered Prime Minister and Parliament have been reduced to lame ducks.

For instance the 19th Amendment debars the President from holding ministerial posts including that of the defence minister. The President has appointed a retired Army General as Defence Ministry Secretary without appointing a Defence Minister. It is Gen. Kamal Gunaratne who calls the shots under the personal instructions of the President while the State Minister of Defence is a virtual non-entity in this sphere.

Genesis of the executive presidency in Sri Lanka

What then has led to this state of affairs? The genesis of the executive presidency in Sri Lanka needs to be examined briefly in order to place current happenings connected to the President, Premier and Parliament in perspective.

As stated earlier it was Junius Richard Jayewardene known as J.R. Jayewardene and JR who masterminded the change of Sri Lanka’s political system from the British Westminster model to that of one closely resembling the French Gaullist Constitution. Power shifted to the president who was transformed from a figurehead to an effective head of state. Nevertheless JR did work through Parliament also by ensuring that the cabinet would consist of Parliament members only. This two-part article will therefore trace the evolution of the executive presidency ushered in by J.R. Jayewardene in the first and scrutinise its present position in the preliminary stages of the Gotabaya Rajapaksa period in the second.

J.R. Jayewardene pursued his goal of creating an executive president that was not dependent on Parliament with great zeal and patience. He first articulated his vision of a presidential system in December 1966.When JR was Minister of State in the UNP Government of Dudley Senanayake (1965-’70) he made a ground-breaking speech at the Association for the Advancement of Science. J.R. Jayewardene in his keynote address of 14 December 1966 outlined his vision for an executive presidency and argued in favour of a presidential system based on the US and French models.

“The Executive will be chosen directly by the people and is not dependent on the Legislature during its period of existence, for a specified number of years. Such an Executive is a strong Executive seated in power for a fixed number of years, not subject to the whims and fancies of an elected Legislature; not afraid to take correct but unpopular decisions because of censure from its parliamentary party,” he said. The essence of JR’s “vision” lies in the words “an Executive chosen directly by the people not dependent on the whims and fancies of an elected Legislature”.

The chance for JR to espouse his executive president vision in the form of a tangible proposal came six years later during the United Front (UF) Government of Sirimavo Bandaranaike (1970-’77). Parliament had converted itself into a Constituent Assembly to draft a new constitution. JR was then the Leader of the Opposition while Dudley Senanayake remained Leader of the UNP.

On 2 July 1971, JR moved a resolution in the Constituent Assembly. It read as follows: “The Executive power of the State shall be vested in the President of the Republic, who shall exercise it in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution. The President of the Republic shall be elected for seven years for one term only by the direct vote of every citizen over 18 years of age. The President of the Republic shall preside over the council of ministers.”

JR’s motion was seconded at the Constituent Assembly by Ranasinghe Premadasa who was then the Colombo Central MP and Chief Opposition Whip. JR argued eloquently, within the Constituent Assembly, in support of an executive presidency. The motion was shot down. The JR-Premadasa motion was rejected by the then Constituent Assembly.

The UF Government brought in the new Republican Constitution on 22 May 1972. The Governor General position under the earlier Soulbury Constitution gave way to the post of President. Power was vested in Parliament known then as the National State Assembly and while President William Gopallawa was the titular Head of State, the real power was retained by Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike.

Dudley Senanayake passed away in 1973 and JR succeeded him as UNP Leader. He soon established his leadership position and brought the party under his full control. JR was now able to pursue his vision of an executive presidency from a strong position.

Parliamentary Elections were held in July 1977. The UNP manifesto of 1977 stated, “Executive power will be vested in a president elected from time to time by the people. The Constitution will also preserve the parliamentary system we are used to and the prime minister will be chosen by the president from the party that commands a majority in Parliament and the ministers of the cabinet would also be elected members of Parliament.”

The change to an executive president from prime ministerial system was a key aspect of the UNP electoral campaign in 1977. The UNP swept the polls and obtained 141 out of the total 168 parliamentary seats. J.R. Jayewardene became Prime Minister in July 1977. He began moving fast towards his cherished vision of an executive presidency.

JR and a small group of ministers and party stalwarts in association with leading lawyer Mark Fernando (later a Supreme Court Judge) started working towards the goal of introducing the executive presidency. The preliminary discussion was on 7 August 1977. An amendment to the Republican Constitution of 1972 was first drafted. After discussions in Cabinet it was approved and certified by the Cabinet as “urgent in the national interest”.

Thereafter it was sent by the Speaker to the Constitutional Court which prevailed at that time, as an “urgent bill”. The Constitutional Court approved the bill within 24 hours as stipulated. It was then presented to the National State Assembly for debating and voting. The bill was adopted by the then National State Assembly on 22 September 1977 as the Second Constitutional Amendment. Executive power was transferred to the President and JR Jayewardene became the first Executive President of Sri Lanka on Independence Day, 4 February 1978.

Replacing the 1972 Constitution with the “JR Constitution”

Meanwhile JR was also working towards the goal of replacing the 1972 Constitution in its entirety with a new one. On 20 October 1977 the National State Assembly passed a resolution enabling the then Speaker Anandatissa de Alwis to appoint a Select Committee for Constitutional Reform. The essence of the select committee mandate was “To consider the revision of the Constitution of the Republic of Sri Lanka and other written law as the committee may consider necessary.” The Parliamentary Select Committee was announced on 3 November 1977.

Initially the Chairman was J.R. Jayewardene who was then representing Colombo West in Parliament. JR however had to vacate Parliament as an MP in February 1978 after he was sworn in as President. Ranasinghe Premadasa who was also serving in the select committee was then appointed Chairman on 23 February 1978 by the Speaker. Premadasa was also appointed Prime Minister.

The executive presidency ushered in through the earlier Second Amendment was now streamlined and incorporated in the new draft Constitution. The Executive President was now Head of State and Head of Government. The electoral system was also changed from the First-Past-the-Post system to that of the proportional representative system. Sri Lanka became a Democratic Socialist Republic. The new Constitution referred to popularly as the “JR Constitution” was formally promulgated on 7 September 1978.

After the presidential system was installed, Prof. Alfred Jeyaratnam Wilson analysed it in his book ‘The Gaullist system in Asia: The Constitution of Sri Lanka’. In it he observed: “What Jayewardene was after was a stable Executive which would not be easily swayed by pressures from within or outside. The outcome in the end was a President who in many ways and can in certain circumstances be more powerful than the French President.” A crucial point to note is that though J.R. Jayewardene introduced a presidential system, he did not provide for a cabinet appointed from outside Parliament. JR was also averse to a powerful Presidential Secretariat as a parallel centre of power to the Cabinet. Why was that?

In response to Prof. Wilson’s specific query on that issue, JR replied, “I must say I am very reluctant to appoint advisers who will be around the president. The reason is that I wish the president to have only his prime minister and the cabinet of ministers as advisers because they represent the people as Members of Parliament.”

J.R. Jayewardene also outlined this position at the convocational address of the University of Sri Lanka on 31 May 1978. This is what he said at the time: “I am the first elected Executive President, Head of State and Head of Government. It is an office of power and thus of responsibility. Since many others will succeed me I wish during my term of office to create precedents that are worthy of following. First, I will always act through the Cabinet and Parliament, preserving the parliamentary system as it existed without diminution of their powers. Second, I will not create a group known as the President’s men and women who will influence him.”

Stranglehold on the Legislature

The prevailing political reality in JR’s time was that the UNP Leader was also in absolute control of the Legislature. What is important to note is the fact that an executive president required full parliamentary strength to be all-powerful.

When J.R. Jayewardene ushered in the presidency he controlled Parliament with a five-sixths majority. Although the executive president was both above as well as independent of the “devalued” Legislature, JR opted to work through Parliament as far as possible because it was his virtual puppet. Besides, doing so reduced the sting in allegations that he had usurped power like a dictator. Thus the gigantic majority of the UNP in Parliament enabled JR to exercise power authoritatively akin to a dictator without being labelled so. For all this full control of Parliament was needed and J.R. Jayewardene continued to retain this stranglehold on the Legislature through several devices of a controversial nature.

JR’s Constitution had debarred MPs from switching parties after being elected. JR prevented the crossing over of MPs from Government to Opposition by constitutional legislation. JR and Premadasa had broad-based the UNP and a large number of “commoners” had been elected in 1977. The class-conscious JR was unsure of the loyalties of the elected representatives of the ‘hoi polloi’. Preventing crossovers therefore was to preserve the stability of the Government. In fact JR even told former Indian Prime Minister Morarji Desai that the Coalition Government headed by Desai may collapse because there was no provision in India to curb fickle MPs. This came true in 1979.

Yet the same JR amended the Constitution he brought in to enable the then TULF Batticaloa MP Chelliah Rajadurai to join the Government. The infamous “Rajadurai” Amendment allowed MPs from the Opposition to join the Government but not the other way about. Another ruse adopted by JR to preserve the gigantic parliamentary majority was the procurement of undated letters of resignation from all his MPs other than from S. Thondaman of the CWC. This deterred potential renegades.

The biggest anti-democratic act of JR Jayewardene was the notorious referendum of 1982. He conducted and won a country-wide referendum which extended the term of office of the Parliament elected in 1977 for another six years. Elections should have been held in 1983. Instead it was put off until 1989 via the referendum. This was to retain the UNP’s five-sixths parliamentary strength until J.R. Jayewardene’s presidency ended. Ironically this was the same JR who objected to the anti-democratic act of the Sirima Bandaranaike Government in extending Parliament’s term by two years from 1975 to ’77. He resigned his Colombo South seat and contested the 1975 by-election to safeguard democracy and romped home the winner. Now JR had no qualms about extending the life of Parliament by six years.

The first of this two-part article concludes after tracing the genesis of Sri Lanka’s first executive presidency ushered in by Junius Richard Jayewardene and outlining how he became a constitutional “dictator” in practice by working through a Parliament over which he had firm control. The second part of this article next week will recount the progress of the executive presidency in Sri Lanka with special emphasis on Gotabaya Rajapaksa who is today a “standalone Executive President not dependent on the Legislature”.

(D.B.S. Jeyaraj can be reached at [email protected].)