Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Tuesday, 27 July 2021 01:39 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The pandemic has further exacerbated income and wealth disparities across different income groups, which are already in a bad situation in Sri Lanka – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

COVID-19 has affected the livelihoods of millions of people across the globe. Apart from the fast-spreading health hazards, the pandemic has caused severe economic setbacks in almost all countries. Lockdowns, travel restrictions, social distancing and other health precautionary measures are severely restraining production and business activities.

COVID-19 has affected the livelihoods of millions of people across the globe. Apart from the fast-spreading health hazards, the pandemic has caused severe economic setbacks in almost all countries. Lockdowns, travel restrictions, social distancing and other health precautionary measures are severely restraining production and business activities.

Worldwide, the pandemic has caused cascading collapse of production, distribution, transportation and financial activities characterised by a vicious combination of supply and demand shocks. At present, the governments are attempting to absorb the shocks by providing a wide range of fiscal and monetary stimulus.

In Sri Lanka, the Government and the Central Bank have launched several stimulus packages since early last year to overcome the economic crisis caused by the pandemic shock.

Diverse economic effects of COVID-19

While the economic consequences of the pandemic vary across countries depending on factors such as the intensity of the pandemic, the economy’s resilience to shocks and the policy response of respective governments, there are variations of the pandemic effects across different production sectors and income groups within each country.

The economic activities that involve face-to-face interaction such as the apparel industry, hotels, tourism and transportation have been extensively impaired by the pandemic than those activities relying on online or remote work arrangements. The casual workers in the informal sector are the worst affected by the pandemic due to job losses.

At the recovery stage, the activities that substitute or reduce personal interactions such as information and communication technologies (ICT) and delivery services grow while the activities depending on face-face-to interactions continue to decline. Given such diversity, economic recovery from the pandemic is sometimes known as a K-shaped recovery.

Recovery shapes

Recovery shapes

Questions have been raised across the world regarding the shape of the economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic applicable to different countries – whether it is V-shaped, U-shaped, W-shaped, L-shaped or K-shaped.

The best-case scenario is the V-shaped recovery in which the economy rebounds quickly after a sharp decline. In a U-shaped recovery, it takes months or years to revive economic activity. In a W-shaped recovery, the economy recovers quickly but falls into a second recession. Hence, it is known as a double-dip recession.

The worst-case scenario is the L-shaped recovery in which the economy fails to recover in the foreseeable future.

Unlike other recovery shapes which focus on overall economic growth, K-shaped recovery is concerned with the divergences between sectoral growth patterns.

V-shaped recovery unlikely for Sri Lanka

In the backdrop of Sri Lanka’s growth slowdown even prior to the pandemic, the V-shaped recovery with an annual GDP growth of 6% projected by the Central Bank is far from reality, as I explained in this column previously (https://www.ft.lk/opinion/Sri-Lanka-unlikely-to-reach-speedy-V-shaped-economic-recovery-amidst-structural-imbalances/14-718615).

Assuming a best possible scenario, hopefully, the economy would revive after two to three years characterised by U-shaped recovery. The bottom of the U shape represents the extended period of the recession before recovery.

A longer post-pandemic U-shaped recovery implies that the economy will take a number of years for recovery. First and foremost, the length of the economic recession depends on how long it takes to eradicate the coronavirus at the national and global levels.

There is the impending danger that delaying the corrective policy decisions might push Sri Lanka towards L-shaped recovery prolonging the pandemic-led recession indefinitely.

What is K-shaped recovery?

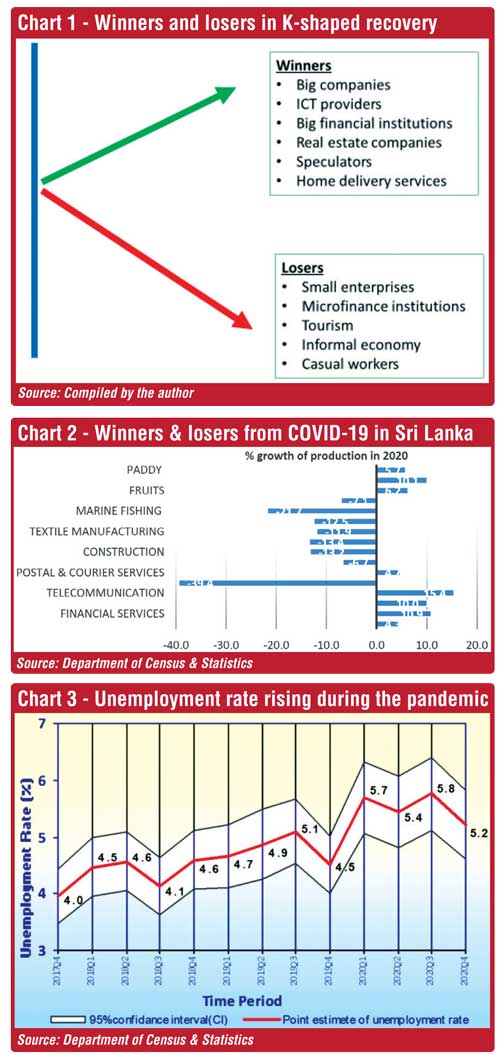

The heterogeneous or diverse recovery across different production sectors following the outbreak of the pandemic is identified as a K-shaped recovery, as illustrated in Chart 1. The upward sloping line of the letter K represents the activities that recover quickly from the pandemic. These include big companies, information and communication technology (ICT) providers, real estate companies and speculators. The downward sloping line shows the sub-sectors that fail to recover from the crisis. They are small enterprises, microfinance institutions and informal sector activities.

As in the case of many countries, the Sri Lankan economy seems to be experiencing a K-shaped recovery from the pandemic. A limited number of production sectors and population segments are thriving during the pandemic while the majority do not recover at all. Financial strengths of individuals and businesses are unequal, and therefore, the rich are able to make exorbitant incomes while poor households representing a major share of the population face job and income losses during the pandemic.

As a result, the pandemic further exacerbates income and wealth disparities across different income groups, which are already in a bad situation in Sri Lanka.

Income and wealth disparities caused by COVID-19

The sectors that require face-to-face interaction including garment industry, hotels and restaurants, air travel, tourism and transportation dipped in 2020. Hotel services contracted by nearly 40% in 2020 (Chart 2).

In contrast, telecommunications, information technology and financial services achieved a remarkable growth during the year. Marine fishing, mining and quarrying, garment manufacturing, furniture manufacturing, construction and transportation are the other sub-sectors that were adversely affected by the pandemic.

Certain blue-chip companies and banks have reported huge profits in 2020. In the meantime, small enterprises are reported to have incurred losses failing to repay their bank debts.

While the regular wage earners are generally unaffected by the crisis, casual workers in the informal sector do not have any means to sustain their livelihood even during normal times. Around 40% of the country’s total number of employees are in the informal sector working as own account workers and unpaid family workers. They are mostly engaged in casual work without having any regular income.

The informal sector consists of less productive small-scale activities. The adverse effects of the pandemic on the informal economy are not clear, as timeseries data are not available for this particular sector. However, it is obvious that this sector is worse hit by the pandemic.

The unequal growth has worsened income and wealth inequality among different sectors and different income groups since the outbreak of the pandemic.

Home delivery services thriving

Home food delivery services have developed fast, particularly in urban areas, during the pandemic, as people dine-in at their homes instead of dine-out due to restrictions. Some home delivery providers in Sri Lanka are reported to have tripled the area served by their grocery service enabling residents to purchase supplies such as cooked food, vegetables, fruits, rice, grains and pulses, dairy products, meat and tea at their doorsteps during the pandemic.

The demand for online groceries more than doubled over the last year due to travel restrictions and households’ preference to safety. The number of grocery partners using online platforms has almost tripled in Sri Lanka over the past year, according to business reports.

Microfinance badly affected

Microfinance is an area badly affected by the health crisis, as their activities are heavily depending on face-to-face interactions in disbursing credit at clients’ doorsteps, collecting repayments and conducting group meetings. The decline in employment and earnings of MFI clients owing to the pandemic has adversely affected their borrowing and debt repayment capacities.

Hence, the operations of microfinance institutions (MFIs) are severely restricted during the pandemic. In this context, improvement of financial sustainability is a formidable challenge faced by MFIs.

Garment industry

The garment industry, being a major foreign exchange earner of the country, provides employment to around 300,000 persons. Around 100,000 are employed in small and medium garment factories. The garment workers were on the frontline of the pandemic last year. Detection of COVID-19 clusters in several garment factories led to suspend their production activities for months.

Export earnings from garments fell by 21% from $ 5,597 million in 2019 to $ 4,423 million in 2020. It is significant to note that the apparel sector recovered remarkably this year recording a 35% increase in export earnings during the first 5 months.

Tourism and travel industry

Tourism, a key sector of the economy, too is adversely affected by the pandemic with the frequent closure of the borders, travel restrictions and social distancing. Tourist arrivals dropped drastically since mid-March 2020. The total number of tourist arrivals declined by 73% from 1,913,702 in 2019 to 507,704 in 2020. As a result, tourism-related activities including transportation, accommodation, personal services and food and beverage service activities have been interrupted in unprecedented scales. Indirect employment in the tourist sector fell by 25% in 2020.

Around 70% of the country’s tourist accommodation is estimated to be in the small and medium sector while the balance represents high-end hotels. There are 156 classified tourist hotels including one-to-five-star hotels, boutique hotels villas and bungalows. Also, there are 1,099 guesthouses, 725 home stay units along with hostels, rented apartments and unclassified tourist hotels totalling 2,164 establishments. There are various services affiliated to tourism such as private vehicle services, vendors at the tourist attractions and residences.

All these services are adversely affected by the pandemic mostly hitting the low-income earners employed in the sector. The contraction of tourism made the largest contribution to the decline in the overall service sector.

Way forward

Sri Lanka’s economic fragility following COVID-19 reflects the urgent need to revamp macroeconomic policies so as to foster high economic growth while maintaining economic stability, particularly with regard to the fiscal and external finances sectors.

However, polices aimed at growth acceleration alone are inadequate since wider economic policies are needed to tackle the unequal economic consequences emerging from the pandemic on different groups of the population, as discussed in this column. The widening income and wealth disparity as a result of the pandemic is a matter of concern.

It is essential to take appropriate action to improve the livelihood of those who are left behind. Opportunities should be available to everybody to harness the growth benefits on an equitable basis by means of inclusive growth.

The pandemic has provided an opportunity to reprioritise policy objectives and to reframe the strategies to make the economy more resilient to future shocks.

(The writer is Emeritus Professor of Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka and a former Director of Statistics, Central Bank of Sri Lanka, reachable at [email protected])