Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Monday, 13 February 2023 00:31 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

|

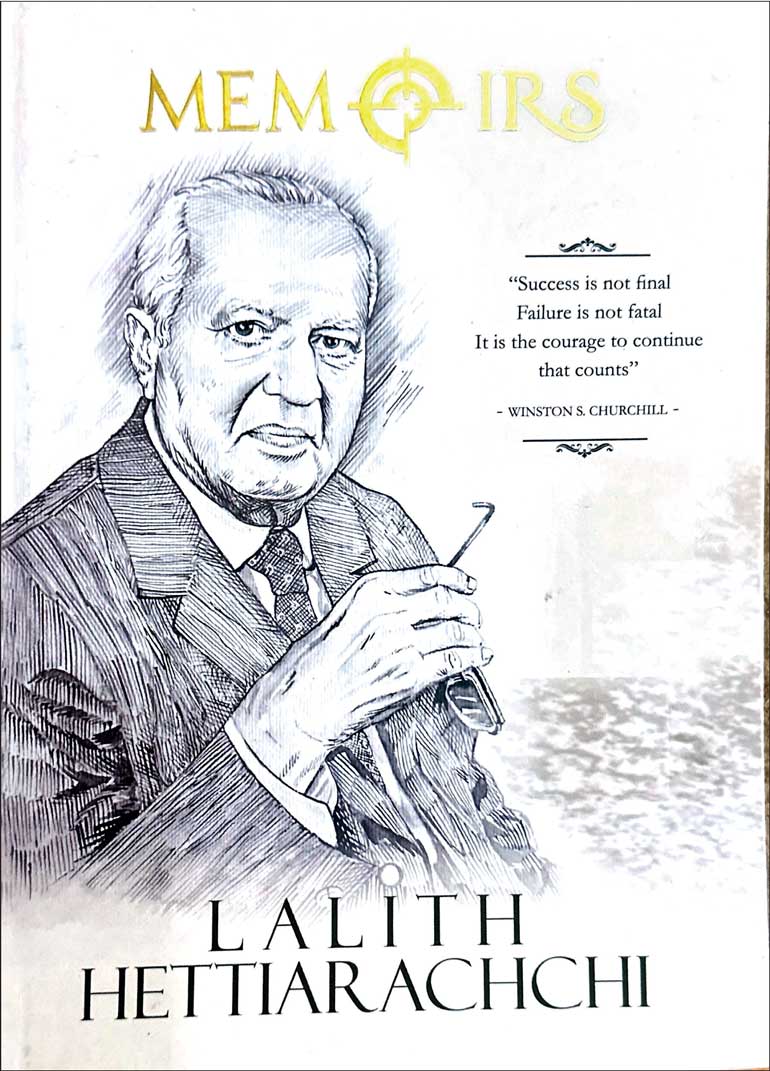

Lalith Hettiarachchi enters the fray via memoirs

It has been customary for senior public servants of yesteryear to pen their experience in the form of memoirs for posterity. The latest to join this group has been Lalith Hettiarachchi, a Sri Lanka Administrative Service officer, who had held many high positions throughout the island. He released his experiences under the title ‘Memoirs’ last month.

It has been customary for senior public servants of yesteryear to pen their experience in the form of memoirs for posterity. The latest to join this group has been Lalith Hettiarachchi, a Sri Lanka Administrative Service officer, who had held many high positions throughout the island. He released his experiences under the title ‘Memoirs’ last month.

Need for strong institutions

When I read through his memoirs, what immediately came to my mind was the thesis presented in the book ‘Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty’ by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson. In that book, the duo has argued that the absence of strong institutions has been the main reason for nations to fail. Institutions in economics are not just formal organisations but values, ethics, and beliefs of people. If they are correctly and properly aligned to the prosperity drive of a nation, that nation succeeds. If they are not, the nation in question fails.

Role of family value systems

Lalith, the second son born to a disrobed Buddhist scholar and a young unsophisticated rural girl many years junior to him, had been inculcated in a value system that is quite different from what we experience today. His father, a vernacular scholar, has been a strict disciplinarian when it came to the behaviours of his children. His word was the law in the house. But his mother was a different specie at all. Born and bred in a typical Sri Lankan rural environment, she had developed an amazing ability to extend love to her children while watching their mischiefs or bursts of anger patiently.

Between a benevolent dictator and an emphatic mother

Lalith recalls that his father, while permitting him and other children in the family to watch how farmers had been working in the paddy fields, had forbidden them to partake any meal or sweet meat served to them. Another inviolable daily ritual in the family prescribed to all of them by their father was to observe Noble Five Precepts or Panchaseela and chant Pirith before they had dinner. It was a patriarchy-centred family and father remained the sole decision maker. When the dinner is ready, Mother would inform Father by herself or through Lalith of it. Then the whole family would sit for the daily ritual and partake the dinner. This was in fact a benevolent authoritarian rule. But its benefit was that Lalith had been disciplined to the core right from his early childhood.

|

Childhood values go a long way

His mother was at the other end. She always displayed patience, toleration, and empathy toward others. It seems that Lalith’s personality got developed by a mixture of these two extremes: discipline from father and empathy from mother. On one occasion when Lalith had falsely accused an old servant woman of stealing a five-cent coin which he had hidden in the storeroom, it was his mother who had pacified him that he should not make allegations against others without proper facts and evidence.

On another occasion, he had broken an earthenware vessel belonging to the mother out of rage, because of the pain he had got by hitting his foot accidentally against a small bench sitting at a corner of the kitchen. Mother had started crying not because she had lost her earthenware vessel but because she could not ask father for money again for the same item. That was because father had been strict on family finances as well. Lalith could not see Mother crying any longer and offered the savings he had kept in small coins in a coin till for her to buy a new vessel.

These two lessons that one should not make false allegations against others without evidence, and one should compensate others who have suffered losses due to his or anyone else’s negligence had been instilled permanently in his value system. He applied this rule to the letter when his peon in Chilaw Labour Office was reported to have lost the office push bicycle when he rode it to the Chilaw town. A proper inquiry was held, evidence led, and after the accused officer was found guilty, he was asked to compensate for the loss.

Doing justice to Chilaw fish market

He has narrated many instances of practicing the same as a public servant. One such story relates to an incident that happened when he was the Assistant Commissioner of Local Governments in Chilaw. At that time, the Chilaw urban council had been dissolved due to some malpractice by its administrators. Hence, Lalith had to officiate as the special commissioner of the urban council as well. In that capacity, one of the critical decisions he had to make was the tendering of the Chilaw fish market.

It so happened that two fish traders, an uncle and a nephew, had been monopolising the tender alternatively by resorting to some irregular practice. They had not allowed any other person to offer a tender to operate the fish market. Lalith’s values that had been built into his institutional structure had told him that this irregularity should not be permitted to be continued. He had permitted a third tenderer, a fish cooperative in Chilaw, to offer a tender as well. After the process was completed, it was this third tenderer who had got the tender breaking for the first time the monopoly held by the uncle-nephew duo. In fact, it was a loss of face for them who had up to that day run the affairs of the fish market as if it is their private property.

Angered by this loss of dignity, they had filed a fundamental rights case in the Supreme Court against Lalith supported by a leading lawyer of the day. The Supreme Court, after listening to the long presentation by that lawyer, had decided to dismiss the case even without hearing the lawyer appearing for Lalith.

In another incident at Chilaw, Lalith had rejected the recommendation by a powerful politician of the day to promote a corrupt worker to the post of overseer at the Urban Council and done justice to another worker who was qualified to take that post. He did not budge even when his boss, under the pressure from that political authority, wanted him to reverse that decision. Since he had kept all the records properly, he was able to prove to his boss that his was the right decision.

|

Standing firm against revenge politics

Political authorities are playing hell in Sri Lanka. When they are in power, they abuse that power too. Public servants are compelled to be a yielding hand to their machinations. Those who object will get immediate transfers to difficult areas. Those who support them can continue in their respective places of work, though they become partners of those corrupt practices. Lalith was an exception, and he did not yield to such unwarranted pressures. In one case, also at Chilaw, the MP for Naththandiya had wanted to take revenge of an ex-Village Council Chairman who was in the opposition camp by acquiring some land he had inherited from his parents for a public cemetery, a public cause. Incidentally, the ex-Chairman’s residence was just behind this proposed cemetery.

When the matter was brought up to Lalith, he visited the place. He says that his conscience did not permit him to recommend that horrible acquisition. But that was not to the liking of the politician in question. He had convened a meeting at his residence, and it had not been Lalith’s practice to attend such meetings. He therefore sought the advice of his boss but to his amazement, his boss had approved of his attending that meeting. Of course, with the recommendation of the Medical Officer of Health in that area that the land so chosen was not suitable for a cemetery, he was able to thwart the wishes of the MP. But later, his boss, the Commissioner of Local Governments, tried to pin him at a departmental meeting.

Lalith stood up for his rights and argued with the Commissioner that what he did was the correct thing as a public servant. The Commissioner had to back down but not before he was fully exposed to his subordinates as an officer without a backbone. That was his value system and that was his institutional setup. It is those institutions that are destructive and do not contribute to society’s wellbeing. The proliferation of such institutions is the main reason for the failure of nations.

|

Motor traffic department: A hellhole of corruption

At the Department of Motor Traffic, as its assistant commissioner, Lalith was a Good Samaritan who fought bribery, corruption, inefficiency, and delays. There was the case of a clerk who had forged the signature of an assistant commissioner and issued an illegal driving licence to a person who had met with an accident. The matter was pursued with support from the Police, and it ended in the dismissal of the errant officer.

Then, one of his teachers at the accountancy classes wanted a quick driving licence before he proceeded to Nigeria for employment in three days’ time. His driving was good but not careful enough, according to the examiner who had given him the driving test. Given the urgency of the matter, he was issued with a licence with a severe warning that he should not start driving until he would get a proper practice.

There was a foreigner who had, due to his ignorance, tried to give a bribe of Rs. 100 to Lalith. He was severely reprimanded about his insolent practice, but no legal action taken. All this work he did with the good intention of serving the people justly, and rightly.

Refusing to enter politics

When Lalith was serving the Department of Information as its Assistant Director, he was offered to enter politics by R. Premadasa on UNP ticket. Lalith says that he declined the offer because he did not want to go into practical politics. But UNP hierarchy was insistent and one day, at his father-in-law’s house, Premadasa had asked him why he did not want to join his team by contesting a seat. He had explained to Premadasa that he did not wish to enter politics and he wanted to serve people as a public servant. Premadasa had told him that he respected Lalith’s decision. As a result, that matter was never pursued by UNP hierarchy.

Corporations are no better

Outside the public service proper, Lalith had served several public corporations as the General Manager. That included Cement Corporation and Gem Corporation. In all these places, he stood tall without compromising his principles and values. That was the institutional setup within him. Only a few public servants of yesteryear could boast of such a quality within them. At the Gem Corporation, when he was asked to be a party to an ill-conceived corrupt project, he refused to be a party.

About this, says Lalith: “I was not prepared to compromise my integrity by getting involved in such an ill-designed project, and in association with a person about whom I had reservations. Therefore, I had to politely reject the offer.” So, without denting his reputation about integrity and probity, he left the Gem Corporation. After a brief stint in the public service proper, he joined the corporation sector once again as Chairman of Sugar Corporation. But he had trouble with the Minister who had tried to interfere in his professional decisions. Though it was an eventful time, he managed to continue as the Chairman of the Sugar Corporation for some time.

|

Standing tall among peers

Lalith Hettiarachchi’s memoirs is a good read for those who like to learn of the way the public servants of yesteryear had performed their duties. Overall, there was the inner drive in them for maintaining integrity and independence. Political authorities had tried to subdue them, but they had managed to function without giving in to their unreasonable and illegal demands. That had been due to the good value system in which they had been inbred. Among them, Lalith stands very tall always maintaining his integrity in all his dealings. In that respect, he is an institution onto himself, a must for preventing a nation from failing. If Sri Lanka has a critical mass – the minimum number needed to effect a change in the system – of such individual institutions, its future course will be different from what we experience today.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)