Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Wednesday, 23 December 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Cabraal on 18 December via a tweet gave the breakdown of immediate Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) under the new Government, referring to Fitch, Moody’s, IMF, the World Bank, HSBC and Deutsche Bank as “doomsayers”.

|

| State Minister of Money and Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms Ajith Nivard Cabraal

|

When global investors who are interested in Sri Lanka’s sovereign bonds had two conference calls facilitated by international banks on 23 and 24 November with Sri Lankan authorities, the investors on

the calls asked the plans about debt repayment in the next four years. These investors, according to two sources who are aware of the calls, are worried about Sri Lanka being pushed to sovereign default with the past rating downgrades.

However, a top official who represented the Sri Lankan authorities on the call spoke about 2021 Budget proposals, its positive outcome and how the Government would get Foreign Direct Investments which would help the country to repay its debts, the two sources said.

But global investors were not convinced about the response. They believe Sri Lanka can manage the 2021 foreign debt repayment with great difficulties without going for either a sovereign bond or an International Monetary Fund (IMF) programme, but they are not confident if the island nation can manage the external debt repayment in 2022 given that Sri Lanka’s borrowing cost is sky rocketing after the two recent rating downgrading.

Towards the end of the same week after these two international calls, Fitch Ratings downgraded Sri Lanka’s sovereign rating for a second time in eight months. This time the rating cut was from “highly speculative” to “substantial credit risk” category, which the rating agency has defined as “default is a real possibility”.

Two weeks later on 11 December, Standards & Poor’s Global Ratings (S&P) also downgraded Sri  Lanka’s sovereign rating for the second time in this year to the similar category. Moody’s Investor Services has already downgraded Sri Lanka to the same category.

Lanka’s sovereign rating for the second time in this year to the similar category. Moody’s Investor Services has already downgraded Sri Lanka to the same category.

The downward movements in Sri Lanka’s sovereign bond yields after the rating downgrade clearly show what the island nation could expect if it goes for an International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs) anytime soon. The 10-year 2024 ISB sold at a coupon rate of 6.85% traded at 25.10% on 18 December Friday, a week after S&P downgraded the rating.

State Minister of Money and Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms Ajith Nivard Cabraal denied that Sri Lanka participated in any such international calls and said: “I have given very clear answers to any question that any investor has asked about Sri Lanka’s debt payments.”

“Hurry to predict debt crisis”

Soon after the S&P’s latest downgrading, Cabraal questioned the independence of the rating agencies and expressed confidence investors would not be distracted by their “ill-advised and subjective” statements.

“Certain agencies which are supposedly ‘independent’ and have been in a great hurry to predict a debt crisis in Sri Lanka as soon as the new Government assumed office in November 2019, are now rushing to suggest that the 2021 Budget is unlikely to boost output and that it will add to fiscal pressures,” Cabraal said in a statement.

The comments by the rating agencies “are directly opposite to those expressed by Sri Lanka business leaders, top economic analysts and other experts who have unequivocally expressed confidence that the new Budget will deal with the debt situation and stimulate enterprises, thereby steering the economy towards stability and growth,” he said.

“Therefore, it seems that the comments of these agencies are being periodically aired to justify their own prophecies, which (fortunately) have failed to ignite a large-scale loss of confidence in the Sri Lankan economy by local and foreign investors.”

Cabraal, the former Central Bank Governor, who gave the leadership to Sri Lanka’s entry into international capital market, also said the comments of the rating agencies “have caused some degree of concern amongst certain groups of investors who had invested in Sri Lankan International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs), prompting them to sell some of their holdings at significant discounts, thereby suffering unnecessary losses”.

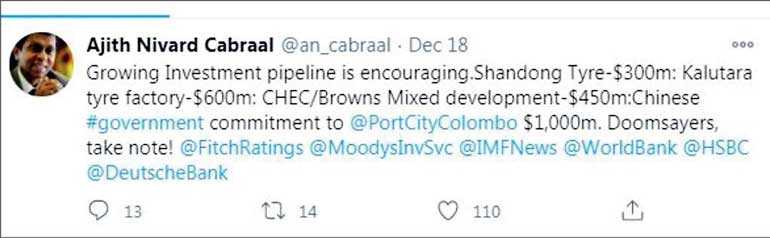

Separately, in responding to these concerns, Cabraal on 18 December via a tweet gave the breakdown of immediate Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) under the new Government, referring to Fitch, Moody’s, IMF, the World Bank, HSBC, and Deutsche Bank as “doomsayers”.

“Growing Investment pipeline is encouraging. Shandong Tyre-$300m: Kalutara tyre factory-$600m: CHEC/Browns Mixed development-$450m: Chinese #government commitment to @PortCityColombo $1,000m. Doomsayers, take note! @FitchRatings @MoodysInvSvc @IMFNews @WorldBank @HSBC @DeutscheBank” he tweeted.

The State Minister’s statement and tweet are self-explanatory on the misalignment between the new Government’s economic policies and international financial agencies including IMF and rating agencies.

Unfortunate rating cuts?

It is unfortunate that even before President Gotabaya Rajapaksa unfolded his firm and long-term economic policies, Sri Lanka’s sovereign rating has been downgraded five times by all three rating agencies. All three rating agencies have repeatedly raised concerns over two key areas: the island nation’s debt sustainability and fiscal prudence. But the authorities have yet to address these two concerns and engage with rating agencies, which were chosen under the 2005-2015 Government of Mahinda Rajapaksa. It is evident that the $ 84 billion economy is struggling to address both concerns amid the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is taking a toll on the otherwise expanding economy even during the final phase of the country’s 26-year war.

Sri Lanka’s key reforms are yet to be announced to boost Government revenue, new revenue measures without burdening the poor are considered to be introduced, and new firm policies to woo foreign investors are yet to be put in place. But it is not a secret that all these measures are dragged and delayed by COVID-19 spreading.

And from bad to worse, the country’s economy is on a contraction; it will be a herculean task for the Government to implement these measures at this juncture. Sri Lanka’s economy contracted by a record 16.3% in the second quarter of this year, the country’s worst-ever growth performance in its history since independence. Though the Government had expected a contraction of a near 1%, global multilateral financial institutions have estimated this year’s growth to be between 5%-7% contraction or negative growth.

Routine denials

It has now become a routine practice: Whatever international rating agencies say, Sri Lankan authorities deny. Earlier the denial was issued by the Central Bank and now it is done through the Finance Ministry. The net result, however, is the same: a blow the country’s borrowing cost internationally. These denials are not going to help the island nation in the long term. We are in for a heavy painful economic shock unless we get our act together and rise against all odds.

Under usual Sri Lankan conspiracy theories, the rating downgrading is seen by some as a deliberate move to push the country towards a sovereign debt crisis. Some others think since the rating agencies are pro-West, they are punishing Sri Lanka’s pro-China alignment.

And some others in apex financial bodies of the Government including the Finance Ministry and the Central Bank think Sri Lanka should be given the chance of benefit of the doubt given it is still struggling with the deadly coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and the new Government has just announced its Budget, thus rating agencies should give some more time to readjust. This could be true to some extent, but these financial authorities have hardly responded to the warnings by the rating agencies before they actually started downgrading the island nation’s ratings.

Though many people in Sri Lanka including professionals do believe that the Sri Lankan economy is “not in that much bad shape,” internationally investors think otherwise because they go by what the rating agencies say. The rating downgrades are seen as the bellwether for Sri Lanka’s ability to repay foreign loans and attract foreign investments in the next few years. A gloomy sentiment has already compelled international investors to pull out of Government bonds despite the Government in September offering to cap forex risks to reduce the country’s dependence on international sovereign bonds.

After rating downgrading by two notches by all three rating agencies in the last eight months, Sri Lanka has fallen into “substantial credit risk category” which means the default is a real possibility. The latest rating downgrade was as recent as last week.

The S&P after its rating downgrade on 11 December said Sri Lanka’s existing funding sources do not appear sufficient to cover its debt servicing needs estimated at over $ 4 billion next year.

“This means that Sri Lanka may need external commercial funding, which can be difficult and costly,” the ratings agency said in its latest report on the $ 84 billion economy. “We see increasing indications that funding from multilateral or bilateral partners will not be sufficient to cover external financing needs over the next 12 months.”

The Government, as in the past, hit back with its usual set of words saying it was disappointed with rating action by S&P at a time when the Parliament has passed the new Government’s first full-year Budget for 2021, “which laid out a carefully-crafted medium term policy framework, alongside a novel orientation for a solid recovery of the economy in the period ahead”.

While many doomsayers criticise Sri Lanka for a looming debt crisis, what they should also understand is nobody, including the rating agencies, has questioned Sri Lanka’s track record on foreign debt repayment. The country has honoured all its external debt obligations in a timely manner. The concerns are only on possibility of a sovereign debt default occurring and the rating agencies’ warning also comes from experience with other countries in the past including Greece.

Hard time ahead

There will be a hard time ahead for Sri Lanka until it engages with rating agencies. The Government is so far determined to not go on an IMF programme, given it could be perceived negatively by voters as the ruling Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) is a strong critic of IMF conditions including increasing taxes and reducing Government expenditure.

However, Sri Lanka’s bilateral lenders, who take the rating downgrades seriously, will adjust themselves. For instance, Agency of France Development (AFD), which works to fight poverty and promote sustainable development, last week said the Sri Lankan Government had requested 200 million euro to fight the COVID-19 pandemic as early as in March, but the group is still waiting for some directions from multilateral agencies from the IMF on Sri Lanka’s macroeconomic stability.

It also said the AFD was ready to raise the portfolio of non-sovereign debt out of available up to 400 million euro available in the next three years to Sri Lanka’s public and private sectors given the island nation’s tight fiscal situation to borrow sovereign loans.

So the impact of the rating downgrades will reflect in unavailability of cheaper sovereign loans for Sri Lanka possibly even by aid agencies. The Government will be compelled to boost FDIs, exports, tourism revenue and remittances, and use its other channels like asking State and private banks which have credibility to borrow dollar loans from foreign funds without sovereign guarantees.

“It is a highly contrasting situation. Sri Lanka has buoyant economy and the situation is really cool in the media and papers, but when you speak to people beyond Sri Lankan shores, we hear all these negative and debt defaulting stories,” said a retired Government official aware of past discussions with rating agencies.

“The authorities seem to be not taking things seriously on preventing rating downgrades. Engaging with rating agencies itself could be credit positive. The Government will have to heavily rely on China for investment and that also might come with strong conditions that could eventually be a burden if we are unable to pay the loans on time.”

Knowing the current debt repayment situation, President Rajapaksa correctly asked the newly-appointed Chinese Ambassador to Sri Lanka Qi Zhenhong for investment instead of debt-driven infrastructures.

“The President stated that Sri Lanka had made it a priority to attract investments instead of further foreign borrowings in its development drive,” his office said in the statement after the meeting with Zhenhong, who presented his credential during the occasion.

Biggest challenge

Sri Lanka’s biggest challenge at the moment is repaying of around $ 4 billion per annum up to at least 2025. The biggest chuck out of this is for the repayment of ISBs and their interest payments. A top Government official last week said this amount was around $ 2 billion every year. Usually Sri Lankan authorities roll over maturing sovereign bonds.

“On paper it looks like all is doomed for Sri Lanka. But it will find its own way to repay the loans. The Government could lease some lands and take some small soft loans here and there. But of course we might not enjoy the credit ratings we enjoyed earlier and it will have an impact on all Sri Lankans,” said a forex analyst asking not to be named.

Though the Government is hopeful about more foreign investments, most of the FDI dollar inflows will go to construction, machineries, and establishment of companies. Those FDI will not go directly to the foreign exchanges reserves, which are under pressure due to loan repayments. But those FDIs will help to generate more tax revenue and foreign inflows through exports in the future and it will take some time.

(The writer is a former Reuters Economic Reporter for Sri Lanka and the current Head of Training at Centre for Investigative Reporting Sri Lanka. He can be reached at [email protected] or via twitter @shiharaneez)