Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Wednesday, 29 September 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

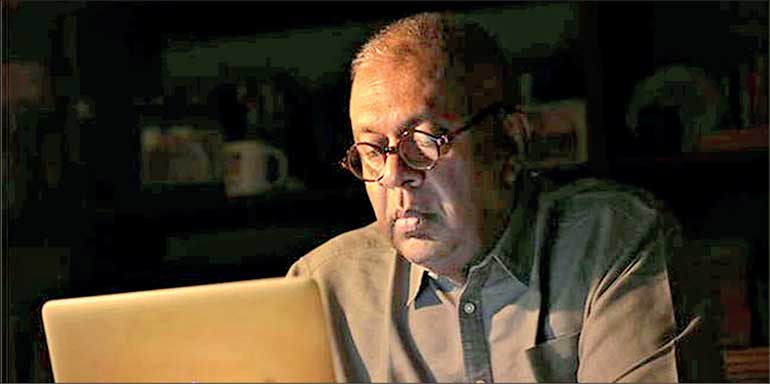

Mangala Samaraweera always cared for those who lived in the dark shadow of oppression; he was often the only leader to speak, or march in solidarity

“This is not a Sinhala-Buddhist country.” This war cry, triumphantly proclaimed in the deepest south after the Easter bombings, were probably Mangala’s most famous words. And rightly so, for they

“This is not a Sinhala-Buddhist country.” This war cry, triumphantly proclaimed in the deepest south after the Easter bombings, were probably Mangala’s most famous words. And rightly so, for they

captured the essence of the man.

The attacks unleashed a volcano of fear and hate, which no one could stop. Most were silent, some tried to soothe. It was only Mangala who dared confront. That confrontation arose from compassion. Compassion which also led him to comfort.

From his Matara home, that served as the office of the Mothers’ Front in the 1980s, to the Eid dinner at his Muslim bodyguard’s home after the attacks, Mangala always cared for those who lived in the dark shadow of oppression. He was often the only leader to speak, or march in solidarity. As a friend put it, with Mangala “power spoke truth”. This is why his loss continues to be felt in every corner of the island and will be for many more years to come.

Mangala’s piercing vision for his beloved Sri Lanka arose from his love of people. His dreams were not sterile blueprints but rich and colourful tapestries woven from the joys, hopes, laughs and tears of the people he encountered. The discrimination he personally felt did not make him bitter. Instead it endowed him with great sensitivity.

He wanted nothing more than for Sri Lankans – individually and collectively – to be free and to reach their fullest potential. To think their own thoughts, do what made them happy and to celebrate life in all its glory.

Amidst the deep disappointment and betrayal he felt after the last Presidential Election – many will remember his tweet from that day – he considered retiring from Sri Lanka to travel the world. That thought vanished, when a few weeks later he went to Matara and met his constituents. They had been by his side for decades and had always accepted him for who he was. Talk of retiring ended. Resolve returned and he began preparing for wrenching Sri Lanka from its post-Independence quagmire.

Courage and wisdom

Courage may be the virtue most lacking in politicians, but wisdom is a close second. As we all know, Mangala was more than a courageous dreamer. He held many of the great offices of State and was, for many years, Colombo’s most influential power-broker. His achievements and regrets have been recounted by others. But Mangala was greater than his office, influence or achievements. He was a leader. His ideas and example were, and remain, a guiding rainbow to us all.

Mangala’s wisdom was practical. In politics and statecraft, noble ends are often necessarily achieved using ignoble means. Knowing this, but also knowing when to stop, when not to cross a line, is the central ethical challenge for any statesman. Mangala was incorruptible. But he also understood that if he did not grant thousands of jobs to his constituents, dreams would remain dreams.

He understood power as only a politician can; he studied its many forms and practiced its many arts. He was a master of the secret alliance, subtle leak, cutting rumour, cunning seating arrangement, selective dinner invite, carefully chosen gift and sincere flattery. Yet it was his conscience’s mastery over the siren song of power and office that made him a statesman, whose stature will wax rather than wane as the years and decades pass. He took laws and institutions seriously. But he knew their limits. Ultimately, power was in politics: in ballots, ideas and emotions. That was his main arena, where he bent perception to shape reality.

I only knew Mangala at a time when this intuition had matured. Yet it is a testament to his spirit that after decades spent at the frontlines of our muddy polity, rather a conscience mutilated and crushed, Mangala Experience had a more refined ethical sensibility than Mangala Innocence. As a tribute from across the aisle put it, he joined politics as a member of the party of conscience and ended life in that party.

Courage and wisdom count for little without capability and ambition. In a country where people move in their tribes – whether family, school, community or class – Mangala saw individuals for who they were. He saw their dreams, recognised their abilities and trusted them when no one else did. He empowered people to do what they always wanted to. He didn’t give a damn about sex, ethnicity, age or anything else. As long as you had passion and wanted to do something, he would quietly be there to help.

He had the genius to unite revolutionary and capitalist, dreamer and fixer, artist and boffin, civil servant and activist, bringing them together to serve progress and serve Sri Lanka. As one person put it, “He made our profession our responsibility.” Just as his friendships reached across the kaduwa, his home and office bridged the English and vernacular universes.

One feature of Mangala’s legacy less remarked on is his quiet record of appointing women to positions of responsibility. Ever the true liberal, he made sure all knew that this was because he thought that those women would do a better job than anyone else, not because they were women. All these people – chosen for their merit and passion, trusted and listened to – repaid Mangala’s trust many-fold. They worked and fought to realise his vision and earn his favour. He was also able to earn the trust and respect of the civil service.

Though politics and art were Mangala’s premier passions, ironically his successes were greater in the economic realm. We all know the SLT revolution paved the way for the privatisation of SriLankan Airlines and SAGT, which has made Colombo one of the world’s great ports. Mangala’s Economics by Deshal de Mel authoritatively demonstrates his tenure as finance minister was no less accomplished than his triumphs as telecoms and foreign minister. Even as a diplomat, Mangala’s economic record is formidable as he played a pivotal role in regaining GSP+ and securing the $ 500 million MCC grant.

With rebellious blue hair, tattoos, Bowie and TikTok, Mangala was a child of Punk London. But he was also an heir of the Victorian tradition in Sri Lankan politics. He was sensible, decent and humble. Underneath that colourful, irreverent personality he carried with him a political tradition of restraint that is nearing extinction. The distinctions between state, government and party were instinctual. He always knew what should (and should not) be said and done in ministry, Parliament and political rally respectively. He abhorred the trappings of power and trinkets of wealth that increasingly found favour among his parliamentary colleagues.

In this age of performativity, Mangala loathed pretence and hated servility even more. He had few friends remaining among his fellow politicians. In Parliament, where dining is largely social, he often ate lonely meals alone in his office. A loneliness presumably made deeper by the many betrayals he experienced over the years, which left him deeply guarded.

I first met Mangala in his Sirikotha lair in the dark days of August 2014 when I was amateur cameraman for Amita Arudpragasam’s constitutional reform film. We talked of Sudu Nelum, we dreamt a bit and we laughed about the dark arts of political gossip sites. Sri Lanka was on his mind. The last time I met Mangala was a few days before he died. As we overlooked the sunny Bolgoda, we dreamt a bit, we laughed at our own bawdy jokes and we talked about his plans to contest in 2024 and the laws we needed to draft in anticipation. Sri Lanka was on his mind.

I do not weep for Mangala. His life was a life of ‘no ragrets’. He lived more in 65 years than many will live in as many lifetimes. I weep for myself and for Sri Lanka. I shall always remember the rally held at the Tagore auditorium in Matara, where Sampanthan and Mangala, representing Point Pedro and Dondra, stood as Palmyrah and Coconut as the young singers called out in Sinhalese and Tamil, to the audience and each other, Peratama Yamu Lanka. As the days and years go by, our sense of loss, of lost opportunities, only grows. This is my way of not giving up: “May the double gem bless us all.”

Mangala Samaraweera died on 24 August 2021. He carried the hopes, often the last hopes, of many. His Lanka may take a few decades more to come to pass. But he believed history was on his side. Mangala is dead, long live Mangala!